A Barnestorming Performance

David Taylor |

Next year the world will commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, said at the time to be the war to end all wars, which of course proved to be nothing of the sort. The Great War’s effect on cricket was to wipe out a large part of the final generation of the ‘Golden Age’ – young cricketers who left school in or around 1914 and who found themselves in the trenches when they might have hoped to be marking out a run-up or donning the pads for another innings. In practical terms, it meant that no first-class cricket was played in England (and very little elsewhere in the world) in the years 1915 to 1918, when Wisden’s largest feature was its pages of obituaries.

The last Test series played before the outbreak of hostilities took place in South Africa between December 1913 and March 1914, when an MCC side captained by John Douglas visited for a five Test series. The team picked was a strong one, and with good reason. Although they’d been well below their best in England during the Triangular Tournament of 1912, even losing to a weakened Australia, the South Africans were very far from the pushovers they had been when MCC first toured there in the late 19th century. Then, the home side was barely of first-class standard (the Tests were only given that status years later), and England were able to win easily even while fielding a few unlikely caps of their own.

By the Edwardian era Test cricket’s third team was considerably stronger. They had beaten England 4-1 at home in 1905-06, with the famous ‘googly quartet’ of Faulkner, Vogler, Schwarz and White very much in the ascendant, and four years later had prevailed 3-2, wrapping up the rubber in the fourth Test. So MCC were very much on their guard when the ship sailed for the Cape in the autumn of 1913. Jack Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes had established themselves as England’s openers two years earlier in Australia, and most of the squad had either been on that tour or taken part in the twin series of 1912 – England’s last home Tests. Perhaps a handful of players – Relf, Booth and Bird – were just short of the highest class, but there was no obvious weak link. One batsman new to Test cricket was introduced: Lionel Tennyson of Hampshire, selected after only ten matches, in which he had managed three centuries. He would have a short but eventful career for England, split in two by the approaching conflict.

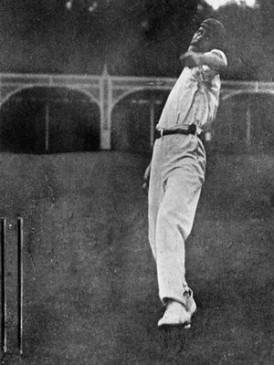

There was no doubt who would take the new ball. Sydney Francis Barnes, better known by his initials, was one of cricket’s great mavericks, a proud professional with a greater sense of his own value to his team and his own reputation than almost anyone else who has played the game. Although Barnes turned 40 in 1913 he had played very little first-class cricket in a career that had started with Warwickshire twenty years earlier – just two full seasons, both for Lancashire. The second of those had been in 1903, since when the great bowler had confined his efforts largely to playing for Staffordshire and in League cricket. In 1913 he had appeared in just four matches, none of them in the County Championship, and taken 35 wickets at ten runs apiece. So long as he was available, and the MCC could meet his terms, his place on the ship was not in doubt.

In fact Barnes was omitted from the first match of the tour, a fixture against Western Province in which MCC managed a draw after being obliged to follow on, and, after picking up 7 for 11 against a Fifteen of South West Districts, he came in for the second first-class match against Cape Province – after Hobbs had given notice of his form with 170 Barnes picked up 2 for 34 and 7 for 25 to ensure an innings win. Another against-odds match brought him another thirteen wickets, and against the more testing opposition of Border he had 4 for 36 and 2 for 21.

So to the first Test at Durban. South Africa’s captain and opening batsman Herbie Taylor won the toss and he and Barnes were the leading players on day one, Taylor making 109 out of a total of 182 while Barnes took 5 for 57 – no other batsman managed 20. Thus in one day the tone for the series was set. England took a decisive lead of 268 with Douglas making 119 – the first instance in Tests of rival captains making hundreds – and South Africa folded for 111, never looking as if they would make England bat again. Barnes took another five including the top scorer, Dave Nourse hit wicket for 46.

Another seven wickets in the tour match against Transvaal kept Barnes in form going into the second Test, at the Old Wanderers ground, Johannesburg, where he was to make history: 8 for 56 in the first innings (including Tancred and Newberry, both stumped, which gives us some indication of his pace) and 9 for 103 in the second. This is still the second best match performance in all Test cricket, and with Rhodes and Mead recording hundreds England again won by an innings. South Africa’s batting was more consistent and in the second inning they passed 200 for the first time in the series, but nobody went on to make the big score that was needed. Despite winning the toss in each match they were 2-0 down.

Even in those days there were back-to-back Tests, and the third match started a few days later, on New Year’s Day 1914. This time England won the toss and made 238, Hobbs top scoring with 92. Taylor contributed with the ball this time, with three cheap wickets. But the home side fell well behind, Barnes taking three wickets and for once playing second fiddle to Hearne, who took five. Consistent scoring from Mead, with 86, and the lower middle order set an unlikely target of 396. But at 153 without loss they were on course to pull off an upset. It was a frustrating time for Barnes, Douglas and the rest of the bowlers but once Taylor and Zulch were separated wickets fell at regular intervals and England’s spearhead finished with yet another five-wicket haul.

Remarkably, more than a month elapsed before the next Test, at ‘the other’ Lord’s, Durban. Barnes continued to cash in with ten wickets in the match against Griqualand West, and thirteen against Orange Free State, passing 100 for the tour (in all matches) in the process. He had a quiet game against Transvaal, with three wickets, then against Natal he came up against Taylor again – and MCC suffered their only defeat of the tour. Natal won by four wickets with Taylor making 91 (out of 153) and 100, and as they closed on victory Barnes moaned “it’s Taylor, Taylor, Taylor all the time!”

Nevertheless South Africa went into the fourth Test at Durban 3-0 down, and Barnes took seven in each innings, despite Taylor making 93 in the second innings. But this time it was South Africa who produced the better batting, and England were left hanging on for the draw. Apparently there was some offer of a performance bonus from the hosts which wasn’t forthcoming, and Barnes refused to play in the final match, or again on the tour. But he had finished with 49 wickets in four Tests, which of course remains a record to this day. Only once has it been seriously approached, when Jim Laker took 46 against the Australians in England in 1956, and with the scarcity of five (and four) Test series the landmark looks secure for the foreseeable future. Barnes took his 49 in a strong attack in which no other England bowler managed more than ten, a freakish performance; generally, you would expect the wickets to be shared out far more evenly over the course of a series. And mention too must go to Taylor, leading his country for the first time – his 508 runs was a remarkable effort for a batsman whose side lost 4-0. It’s difficult to think of an equivalent performance from a batsman whose side lost the series so comprehensively; perhaps Brian Lara in Sri Lanka in 2001-02 (688 runs in three Tests), or Michael Vaughan in Australia the following year.

At the time of his last Test Barnes’s 189 wickets left him well clear of the pack as England’s leading wicket-taker. Of course he’s been passed many time since then, initially by Alec Bedser, his successor as the country’s greatest medium-fast bowler and the first Englishman to reach 200, but the fact that he’s still mentioned regularly in all-time England XIs is testament enough to the genius of this extraordinary cricketer.

In writing this article Andrew Searle’s book, “Sydney Barnes – His Life and Times”, was of considerable assistance.

I’ve always wondered whether the South Africans bothered to use matting over their wickets again after Barnes’ 49 wickets, and a 4-0 loss. One would hope not.

Also, it’s one of cricket’s great frustrations that there is no significant footage of Barnes bowling so we can all get a proper idea of what he really bowled. Why no idiot thought to shoot 10 minutes of him in close-up action with some 17mm film, and then stick it somewhere safe, beats me.

Comment by watson | 12:00am BST 22 October 2013

wonderful write up, and great cricketer Barnes was, funny that he was a different kind of new ball bowler to what we’ve become accustomed to now. Even postWW2 its more a rarity to see anyone but a full pace bowler get the new ball. Not express necessarily but nothing like Barnes.

Comment by schearzie | 12:00am BST 22 October 2013