Tom Armitage: England’s Number One

David Mutton |

Not many people would claim that Tom Armitage was England’s greatest test match cricketer. But he was the first. His presence in what was later designated the inaugural test match, at Melbourne in March 1877, combined with the alphabetic advantage inherent in his last name to ensure that Armitage tops the roll of England’s international cricketers.

Armitage was included in the party for the Australian tour on the back of just two seasons as a professional for Yorkshire. Born and raised in Sheffield, he was first engaged, aged 21, with the Longsight Club in Manchester in 1869 and moved to Keighley the following season where he gained prominence by taking 18 wickets against Wakefield in 1872. He played for Keighley until his breakthrough into county cricket in 1875, and also turned out for Wednesday Cricket Club, which evolved into Sheffield Wednesday Football Club.

Armitage was listed in Scores and Biographies as 5ft 10 inches tall and weighing 12st 10lb. The latter measurement caused mirth amongst his Yorkshire colleagues; Rev. Edmund Carter cattily commented that Armitage was “not a skeleton”, while Tom Emmett compared him and the slight Louis Hall to “law and order” and “shadow and substance.” Scores and Biographies went on to describe Armitage as “an excellent bat and field anywhere, and a straight round-armed middle-paced bowler, combined with underhanded lobs, which at times have been very successful.”

Armitage prospered in his brief Yorkshire career with this combination of lobs and round-arm bowling. He took 22 wickets at just 7.59 in his debut season, including a match-winning 5 for 8 in just 4 overs against Nottinghamshire. The following season he managed 45 wickets in 12 games, including a remarkable 13 for 46 in the match against Surrey at his home ground of Bramall Lane, achieved mainly with lobs. He also struck 95 that year against Middlesex, the highest of his four first-class half-centuries.

The elder statesmen of English cricket, James Southerton, called Armitage’s lobs the best he had ever seen, and persuaded James Lillywhite that the Yorkshireman was worthy of inclusion for the Australian tour. It had been three years since W.G. Grace led the last such trip but neither side remembered it with much fondness. The locals were frequently angered and offended by the good doctor’s brusque behaviour; his professional teammates bristled that Grace lodged them in inferior hotels and that he received almost ten times their fee for the tour. The bitterness was still fresh three years later, and Lillywhite chose an all-professional team. The twelve men were each paid ?150 plus expenses (with the exception of Alfred Shaw, the star of the show, who received ?300).

Armitage had a stinker of a tour; even his Wisden obituary termed him “a failure in Australia.” His first egregious error came against a Victorian XV when he dropped Tom Horan, who went on to score a match-winning innings. This Victorian victory led to Australian demands for an eleven-per-side match with the tourists. It was the first time that a colonial team had been deemed worthy of such an honour, and was the primary reason that the game was later elevated to test status.

Neither team was at their strongest for the first test match. The all-professional status of the tour meant that England could not call on the genius of W.G. Grace or several of the era’s other talented amateur batsmen, and the original twelve had been reduced to eleven after Ted Pooley was detained in New Zealand following a fight over a gambling debt. Meanwhile Australia were without their demon bowler, Fred Spofforth, who withdrew his name after the selectors omitted William Murdoch, the only man Spofforth considered competent to keep to his bowling.

4,000 spectators came to the Melbourne Cricket Ground on the first day, and they watched Charles Bannerman strike a superlative century for the Australians. He offered one chance, while still in single figures, but Armitage, fielding at mid-off, let the ball hit his ample belly and drop to the ground. The Yorkshireman only bowled three overs and rolled out both lobs and round-arm but nothing went right. One ball sailed straight over the batsman’s head and the next rolled all along the ground.

12,000 Melburnians cheered their hero Bannerman on during the second day until a George Ulyett delivery split his index finger. The opener’s 165 out of Australia’s total of 245 has remained the highest percentage of a team score throughout the subsequent 2,000 test matches. Armitage was confident that he could dig his side out of trouble and wagered with his captain, Lillywhite, that he would make a fifty. He lost the bet. Caught behind off the bowling of Billy Midwinter for nine runs, Armitage was then out for only three in the second innings as England capitulated to a 45 run defeat.

In the aftermath of the victory The Melbourne Age celebrated the progress of Australian cricket; “such an event”, the newspaper wrote, “would not have been dreamed of as coming within the limits of possibility ten or fifteen years ago.” When the news finally reached London two months later, The Times’ reaction was less generous, with the snide remark that “Lillywhite’s pecuniary success must have consoled him for his defeat.”

Whether to avenge defeat or earn extra ticket sales, Lillywhite arranged a second game against the Australians a couple of weeks later. This time Spofforth played but England exacted revenge with a four-wicket win. Armitage’s role was even more limited than in the first match; Lillywhite did not trust him with the ball and demoted him three places to ninth in the batting order.

One Melbourne newspaper wrote that Armitage “has brought no small reputation to Australia, but seems to have thrown his skill overboard on the passage out.” In Armitage’s defence the first test took place just after the team had returned from the New Zealand leg of the tour. He reportedly suffered from seasickness on the boat back across the Tasman Sea and was barely able to stand on the morning of the test match. Whether this was due to the remnants of sea legs or less salubrious reasons is open to question for Scores and Biographies blamed England’s losses on “fatigue, owing principally to the distance they had to travel to each match, to sickness and to high living.”

The sojourn into New Zealand also led to a fabled story of Armitage’s gallantry. Alfred Shaw wrote in his memoirs about the trip from Hokitika to Christchurch. The party set off early on Friday morning on a journey they hoped would take 36 hours. However flash floods soon made the roads hazardous, and when the team’s two coaches arrived at what was usually a shallow dam they encountered a deep river. One coach successfully navigated the treacherous waters but the second became stuck midstream when the horses refused to go any further. Armitage heroically carried the sole female passenger to safety as the other passengers pulled the horses and the coaches out of the water.

Upon returning to the mother country, Armitage played on with Yorkshire for two more seasons and then, aged just 30, he was effectively done with English cricket. He had scored 1,053 runs for the county at an average of 13.67 and had taken 107 wickets at 15.08. There was a final first-class game on home soil the following year for the United North of England against a London United side, but Armitage did not bowl and batted ninth.

His county career behind him, Armitage moved on to the most common occupation for retired cricketers of the Victorian years. In 1879 he became the publican of the Plough Inn, opposite Hallam Football and Cricket Ground in his native Sheffield. It was there that tragedy first struck. His wife, Mary Ellen, succumbed to tuberculosis, leaving two small children, Herbert and Hannah.

Despite a second marriage, to Evangeline Bryan Standell, the servant at the Plough Inn, there seem to have been too many memories of Mary Ellen at the pub. In 1886 he set out on a new venture, and a new country, as the professional for the Oxford Cricket Club in Philadelphia. Armitage was a big fish in the relatively small world of Philadelphian cricket. He ran through smaller clubs such as Baltimore, where he took 11 wickets in the match for 55 runs but his bowling also destroyed the city’s prestigious teams, including remarkable figures of 9 for 17 against the Philadelphia Cricket Club. Armitage was also roped in to Philadelphia’s annual attempt to replicate England’s Gentlemen against Players series. In a match somewhat strangely awarded first-class status, he scored a half-century and took two wickets in a crushing victory for the Players of the United States of America against the Gentlemen of Philadelphia. It was his final first-class game.

Armitage returned to Sheffield in 1887, and reunited with Evangeline, with whom he had three children: Thomas, Samuel, and Ruth. Before long he was back across the Atlantic, this time with family in tow. The Armitages set up home in Chicago, and on 16 November 1888 he started work for the Pullman Car Company as a marble cutter.

By the time Armitage began work at George Pullman’s business it was synonymous with the American railroads. The company built luxury sleeper cars which for the first enabled passengers, at least those with enough money, to enjoy rather than merely tolerate cross-country trips. Along with the swanky surroundings came legendary service from the thousands of predominantly African American Pullman porters. At its height, the business was the largest hotelier in the world, providing respite for 40,000 people each night. Before automobiles and long before planes, Pullman cars opened up America for the wealthy.

Such glamour and decadence was far removed from Armitage’s day job. His new occupation was actually a family trade. His father and brothers were stonemasons, and family lore had it that one of his brothers emigrated to Australia after hearing Tom wax lyrical about its high-quality stone.

But Armitage’s days cutting stone were few. After only eighteen months the old cricketer left the Pullman Car Company and went back to serving alcohol. However his saloon was not in the company town of Pullman. George Pullman built his eponymous model industrial town, the first of its kind in the country, to ensure that his employees were not led astray by the many vices of Chicago. He provided parks, theatres, decent housing, and a library but newspapers, public speeches, town meetings, as well as grog, were off limits.

One of Pullman’s approved pursuits was cricket. Indeed it is probable that despite Armitage’s masonry background it was his ability with bat and ball that led to his employment. With many immigrants from northern England and a large number of Canadians, cricket was reputed to be the most popular sport in the town. There were enough players that Pullman fielded a second team and even before Armitage arrived they regularly played against and often beat the elite Chicago Cricket Club. With the old professional on the team, who opened the batting, they dominated all-comers and lost only three out of forty contests between 1887 and 1890.

Pullman controlled his town with an iron grip but the surrounding locales were more accommodating to his thirsty workers, who simply went across the town limits for a drink. More than 100 saloons were located in nearby Kensington, Roseland and Gano, and Armitage set up in Kensington. He was still pulling pints during the Pullman Strike of 1894, when 4,000 workers in the town walked out in protest over redundancies, reduced wages, and high rents. The protests quickly spread and brought most of the nation’s trains, and therefore its transport infrastructure, to a halt. The federal government responded with an injunction ordering strikers to cease or risk losing their jobs, and President Grover Cleveland sent in the army to enforce the ruling. Amidst rioting, and the loss of at least 30 lives, the trains began running again.

The strike would have hurt Armitage’s business. The union leaders mirrored their enemy by discouraging their men from drinking in pubs for fear of the bad publicity from fights. By then, though, tragedy had again struck at the heart of the Armitage family. In May 1891 his two young sons, Thomas and Samuel, died from diphtheria. Whatever the ultimate reason, life became intolerable for Armitage and in August 1894 he was confined to the Illinois Eastern Hospital for the Insane at Kankakee.

The institution, about thirty miles from Chicago, housed 2,000 men and women, but was not the archetypal Victorian hellhole. Considerable improvements had been made since a fire swept the building a decade previously and killed seventeen people, and although it still housed violent patients the criminally insane had been moved into their own hospital two years earlier. But regardless of the hospital’s progressive regime, which included a farm, dairy, and regular instructional classes, Armitage’s condition must have been pitiable. A Mr. J.G. Davis described Armitage’s Lear-like plight in the 26 November 1896 issue of Cricket: A Weekly Record. He waited at table, Davis wrote, and was “perfectly sane on most subjects, and told a friend, recently, that looking after these crazy beggars was the easiest job he had ever had in his life, and he would be a fool to give it up.”

Armitage was discharged on 1 December 1896 and went back to cutting stone for the Pullman Car Company. His job was not stable; he worked until 1904, then was laid off for short intervals, and finally secured regular employment in 1912. As a way of supplementing this unsteady income Armitage was Pullman Cricket Club’s groundsman but the club’s glory days had passed. When Pullman died in 1897 the Illinois Supreme Court demanded that his estate sell its assets, which included all the property in the town. The sports facilities soon fell into disrepair, and the grandstands were demolished.

The club’s old-timers soldiered on but it was a losing battle. In 1907 they were all out for 0 against Hyde Park and Pullman pulled out of the league in 1911. There was a final resuscitation in 1913, when Spalding’s Cricket Guide mentioned Pullman putting out a team, led by veterans including Armitage. But it was a final fling and the club closed in 1914.

By then Armitage had known loss for a final time, with Evangeline’s death in 1907. His last years were spent living with his daughter, Ruth, and her husband. It was in their home that he died, on 21 September 1922, at the age of 74, from stomach cancer. A few weeks earlier his native county had won the county championship. At this remove it is impossible to know whether Armitage paid any attention to that domineering Yorkshire side which lost only two first class matches all season, with Herbert Sutcliffe at its helm and Wilfred Rhodes as its soul. But cricket was the one consistent thread in a life pocked with tragedy and hardship, and it is a hopeful thought that the success of his old county might have offered the old Yorkshireman a modicum of solace in his final days.

Nice piece David, and before benchy asks no I never saw him play, mind you only ‘cos we didn’t have a tellybox in those days

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am BST 18 October 2013

Cheers Fred. And thanks again for the help with the research.

Comment by davidmutton | 12:00am BST 18 October 2013

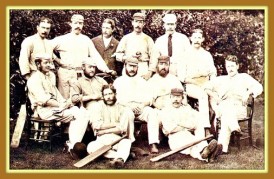

Is the photo of the touring team in 1877? Can Armitage be identified in it?

Comment by Hugh Waterhouse | 12:00am BST 27 June 2014