Masterly Batting – Part Three

Dave Wilson |

In 2012, Patrick Ferriday’s first book When the Lights Went Out, covering the 1912 triangular tournament, was voted CricketWeb’s Book of the Year. Patrick’s new book, Masterly Batting – 100 Great Test Innings, is due out next month and is illuminated by contributions from the likes of David Frith and Ken Piesse writing on their boyhood heroes, Stephen Chalke on one of the greats of the inter-war years – Rob Smyth and Telford Vice on modern giants and Derek Pringle writing from the best view in the house, the other end of the pitch. Innings were assessed on ten major categories on both a subjective and an objective basis, including strength of bowling attack, conditions (and how they affected the attack), match and series impact and chances given, as well as such as intangibles as captaincy, trying circumstances, protection of the tail (or not) and running out team-mates.

All eras of Test cricket are represented, from the 19th century to 2012 and as might be expected many great names are featured, some on more than one occasion. Several high-profile names who might be expected to feature ae conspicuous by their absence, such as Denis Compton and George Headley, while others who would never get near a discussion of the greatest batting legends enjoy an entry (take a bow, Darryl Cullinan and Azhar Mahmood) – that’s what can happen when individual innings rather than batsmen are considered. The book is configured of 500-word essays on the innings ranked from 100 down to 51, 1000 words on those ranked 49 to 25 and finally 3000 words on the top 25.

CricketWeb is delighted that contributions have also been made by no fewer than six of our feature writers – Martin Chandler, Sean Ehlers, David Taylor, Gareth Bland, David Mutton and Dave Wilson. As a taster for the book’s upcoming release we are proud to present several extracts from each of our authors, in this third part featuring David Mutton and Gareth Bland.

hashim Amla – 311*

England v South Africa, The Oval 19-23 July 2012

by David Mutton

Cricket’s lumbering scheduling may never allow for a world Test championship but at least 2012 matched the two best teams for three matches. The first Test, at the Oval, with Lord’s being the temporary home of Olympic archery, promised the tantalizing prospect of a tussle between England’s destructive bowlers and South Africa’s immovable batsmen.

An Alastair Cook century ensured steady if unspectacular progress for England on the first day but this would prove to be their apex in the series, with a collapse to 385 on day two. Given the conditions, only respectable but, given the bowling, there were grounds for optimism and home hopes were raised when Alviro Petersen was out for a duck. This brought in Hashim Amla to join his captain. With two hours left to play under cloudy skies and occasional showers this was a series-deciding session – a few wickets and South Africa would be facing an uphill struggle. Graeme Smith and Amla calmly weathered the storm and with a close-of-play score of 86-1 the omens for England were now ominous.

Day three brought sunshine and a bounty of runs for Smith and Amla, a study in contrasts. South Africa’s lumbering, left-handed captain scored almost three-quarters of his runs on the leg-side, brute force his greatest ally, whereas Amla dismantled England’s bowling with timing, soft hands and balance. The broadsword and the scimitar. Smith’s dismissal for 131 merely brought more punishment for England’s bowlers. His replacement, Jacques Kallis, effortlessly accumulated runs whilst Amla marched elegantly onwards, peppering the off-side, sometimes toying with England by stroking the ball to recently vacated areas.

Amla’s batting felt like an extension of his personality, an aura of calm concentration enveloping him at the crease. There were no raucous celebrations when reaching milestones; he simply acknowledged the crowd’s warmth and proceeded serenely onwards, adrenaline his enemy. Beneath this composure was the steely core evident throughout his career, allowing him to overcome a rocky start in international cricket and ignore the carping that he had been chosen on colour rather than ability. At the Oval that personality and marvelous touch and eye enabled him to remorselessly decimate England’s tiring bowlers.

The pair accelerated on the fourth day. Never hoicking or slogging, Amla simply readjusted his internal algorithms, caressing balls to areas previously ignored. By the time Smith called a halt, Amla’s 311 was the highest Test score by any South African.

England’s batsmen then folded to the pace of Dale Steyn. Losing the match by an innings they never came close to matching South Africa throughout the series. This contest between the two leading teams determined the primacy of one and confirmed that Amla was South Africa’s greatest batsmen since another Durban High School alumni, Barry Richards.

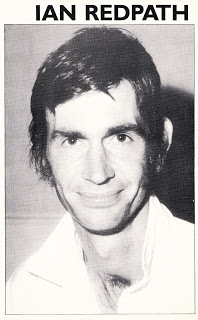

Ian Redpath – 159*

New Zealand v Australia, Auckland 22-24 March 1974

by Gareth Bland

Ian Redpath’s fourth Test century came during the final match of a three-Test series in New Zealand in early 1974. Following a series of equal length in Australia just weeks earlier in which Redpath did not appear, the first encounter between the two countries since the inaugural Test in New Zealand in 1946, Ian Chappell’s team crossed the Tasman to face Bevan Congdon’s men on their turf full of confidence after a 2-0 home victory. The first match in Wellington had been drawn and with the Kiwis recording a historic five-wicket win in Christchurch a week later Australia now needed to win to level the series – a situation they had hardly envisaged a month earlier.

In its report, Wisden described the standard of pitches for the series as: ‘rather like the three bears’ porridge, chairs and beds: but the just right one was at Christchurch, and the strip at Eden Park Auckland, was as harshly criticised for its vices as was the Wellington one for being over-virtuous.’

In a contest completed in three days, 18 wickets fell on the first day alone. Australia, batting first, were indebted to a superb, unbeaten 104 from Doug Walters and in reply New Zealand were shot out for 112 by Gilmour and Mallett. Two completed innings in under 77 overs; the problems facing the batsmen were not those created by a speedy surface, but rather by a wet one that had been watered too late in its preparation prior to the Test.

In the Australian second innings, Stackpole fell for a duck with the score at two but from then on Redpath went on the counter-attack. Forty-five runs came in the first six overs as he was accompanied by first Ian and then Greg Chappell. With occasionally wayward bowling from the Hadlee brothers early in the piece, Redpath led the charge in helping Australia post their century in 70 minutes. Accurate bowling from Congdon and a miserly Hedley Howarth, the slow left-armer, still had to be surmounted though, and the dampness and lack of pace made strokeplay uncommonly difficult.

It was Redpath’s skill in counter-attacking in such conditions that swung the match for Australia. By turns watchful and aggressive, he hit 20 fours from 310 deliveries and gave not one chance in almost six hours. In a historic series suffused with national pride, tensions inevitably rose to the surface. Redpath, according to Glenn Turner, had batted like ‘an English pro’ as he became only the seventh Australian to carry his bat through a completed Test innings – his unbeaten 159 was more than the New Zealanders managed in their second innings. On a surface where the ball was still, according to Wisden, ‘moving about, jumping or keeping down from the many divots taken from the pitch’, Max Walker was too much for all bar Turner and Australia levelled the series and handsomely saved face.

Leave a comment