Tangled up in Blue

Martin Chandler |

When I was a lad, to steal the title of his autobiography from one of Yorkshire’s finest writers, one of the more remarkable cricketing records, and one which I have no doubt will stand in perpetuity, belonged to Jimmy Binks. He made his debut for the County of the Broad Acres in 1955 and between then and his retirement, at the end of the 1969 season, he played in every single County Championship match that Yorkshire were involved in – 416 of them. In fact in all that time he missed only one Yorkshire fixture, against Oxford University, an occasion when he accepted an invitation to play for the MCC against Surrey instead – so overall it was 491 out of 492.

Being a diehard Lancashire supporter I naturally took an interest in events on t’other side o’ Pennines, and the emergence the following season of Neil Smith as Binks’ successor. I quite liked Smith, a big scruffy looking lad, who was a sound enough ‘keeper but one who did not really look the part. For the 1973 season he moved to Essex where he enjoyed a decade long career.

June 3, 1970 was a big day for me as I reached double figures, my tenth birthday. Wisden tells me that Lancashire didn’t have a game that day, so that is perhaps part of why I took a bit more interest than usual in Yorkshire’s game at Bradford against Gloucestershire, or maybe it was because the White Rose lost (they didn’t do that very often in those days) and that better still they lost to a bunch of “southern softies”. Gloucestershire went on to finish last in the Championship that summer. Those factors apart the main reason was the story that an 18 year old David Bairstow had sat an A Level exam at 6am that morning in order to free him up to make his First Class debut in the game – it set what I considered to be an important precedent, which at 10 I had every intention of following up with a Red Rose equivalent, although in the event I never got remotely close to doing so.

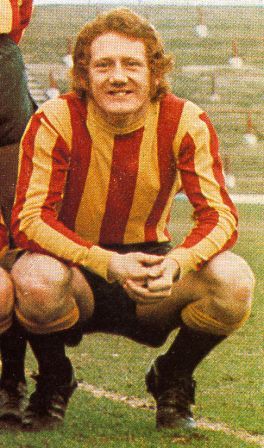

I cannot now recall exactly when I first saw Bairstow play, but it was certainly that summer of 1970, as the commentators were still debating whether he or Smith would get the nod in the long term, and it was clear by the following year that Bairstow had made the place his own. He made an immediate impression on me, although not quite as much as he would have had I realised he had flaming red hair (I had a deprived childhood – we didn’t get colour TV until 1971). But I did notice he was a little bloke (he became a big one) with a big voice (he never lost that) and a big heart (nor that).

As soon as Bairstow arrived in the Yorkshire dressing room he was christened “Bluey” by Jackie Hampshire, on account of his red hair (that’s Yorkies for you!), and that was the name the public came to know him by. His alternative nickname, more often used by his teammates, was Stanley, after the author Stan Barstow, whose magnificent 1960 novel, A Kind of Loving, I would unhesitatingly recommend – don’t be misled by the title – it is as good a portrayal of ‘real’ life as has ever appeared in fiction. But I digress. At a time when Yorkshire cricket was riven by internal strife Bairstow was universally popular, summed up by Geoffrey Boycott as the sort of bloke you would want guarding your back in a dark alley

Bairstow played for Yorkshire for twenty years, three of them in the mid 1980s as skipper, and he also appeared for England in four Tests and 21 ODIs. As that record suggests he was just short of the highest class. His cricketing talents were famously summed up by teammate Phil Carrick thus; He wasn’t a great batsman, he wasn’t even a great wicketkeeper, but he was a great cricketer. His Test career was limited as much as anything by the competition he faced. He was neither as good a keeper or batsman as Alan Knott, and his better batting did not make up for the gulf in class between his keeping and that of Bob Taylor, and although Bairstow didn’t agree, he wasn’t quite as good as Taylor’s successor, Paul Downton, either.

I do however vividly remember one of Bairstow’s Tests, at Headingley against West Indies in 1980. Conditions were not good for batting and, after a blank first day, Viv Richards won the toss and invited England to bat. The innings was in ruins by the time, at 59-6, Bairstow strode out to join his captain, Ian Botham. He soon hit Michael Holding for four consecutive boundaries, and if his 40 wasn’t enough to give England a decent score, its value was put in context by the fact that only Desi Haynes, with 42, surpassed him for the visitors. Sadly for his hopes of further caps Gordon Greenidge had a let off early in the West Indies innings when Bairstow failed to go for a nick that flew between him and slip, and then the fourth day was lost to the weather. England made a better fist of their second innings, and Bairstow was undefeated when the game ended – so had it not been for the Yorkshire weather he might have helped his country to a famous victory.

For a man who eventually did give up, with tragic finality, the abiding memory of Bairstow is of a man for whom no cause was ever lost however hopeless it might appear, as two famous examples amply illustrate. The first was in January 1980 in an ODI against Australia and is, in simple terms, a modern adaptation of the famous 1902 We’ll get ’em in singles exchange between Wilfred Rhodes and George Hirst. The game was a low scoring one and, chasing 164, England’s eighth wicket fell at 129. Bairstow was joined by his county teammate Graham Stevenson, who was making his England debut, and greeted the youngster with Evening old son, we can piss this, and of course they did.

The second was in 1981 and came in a 55 over per side Benson and Hedges Cup match. Derbyshire scored a none too imposing 202 in their 55 overs but, with Yorkshire on 64-5 after all but half their allocation, it looked like more than enough. Bairstow came in then and started to bang the ball about and charge between the wickets in his inimitable style, but all was surely lost by the 46th over when, at 123-9 Mark Johnson, a 23 year old pace bowler making his first team debut, came out to join Bairstow. Obviously it wasn’t, as I wouldn’t be telling the story if it was, but Bairstow’s finale was remarkable by any standard, 26 runs from the 50th over ensuring victory came with more than an over to spare. Of the last wicket partnership of 80 Johnson scored just four, and if you want a further measure of the quality of Bairstow’s batting, and the skill with which he shepherded Johnson, that four matched the young bowler’s total First Class aggregate of runs from the four First Class matches that he eventually played.

The captaincy of his county came Bairstow’s way in 1984. The previous season Yorkshire had, under a 51 year old Ray Illingworth, finished last in the Championship for the first time in their history. Bairstow was the obvious choice, although the job was offered to him only if he played purely as a batsman. Rightly judging the strength of his position he refused, and the condition was removed, and Steven Rhodes went to Worcestershire. No great tactician Bairstow brought, in the main, belligerence and aggression to his captaincy which was aptly described as a series of uphill cavalry charges. The resources at Bairstow’s disposal were as slender as at any time in the county’s history, but there was an improvement each year as in the Championship they finished 14th, 11th and then 10th over the period of his tenure, and in the first season came within just four runs of a Lord’s final.

It was at the end of the summer of 1990 that Brian Close informed Bairstow that his contract would not be renewed. He was nearly 39, but he thought he was worth another couple of years, and doubtless hadn’t properly prepared himself for what his form and fitness over the summer just gone had clearly indicated was going to occur. It cannot have been an easy time for Bairstow. In 1982 teammate Hampshire had written some prescient words in his benefit brochure It is probably fair to say that he does at times have fits of depression….. Perhaps it was the fact that in that 1990 season he had become only the second Yorkshire player ever to be rewarded with a Testimonial, in effect a second benefit, that lulled him into a false sense of security.

Bairstow wasn’t a superstar and, like any professional cricketer of his time, did not have the means to enjoy a lavish lifestyle even if he had wanted to. Two benefits were of course useful, but a man like Bairstow still had to earn a living once he left the game and, save for the eloquent, erudite or very fortunate media opportunities were few and far between. Still at least professional cricketers knew all about the daily grind, but they also had the safe haven of the team spirit and camaraderie of a County club, as well as the recognition and, in some cases, adulation of their admirers, and the loss of those sources of support hit the garrulous Bairstow very hard indeed.

Many before Bairstow have found the adjustment difficult and it seems he was no different. He did some merchandising and public relations work, neither of which were particularly successful. He also found some congenial employment as a summariser for local radio which, given he was such a rumbustuous individual, I would not have expected him to be very good at – in fact he was, but such work was by its nature seasonal, and not particularly lucrative. He remained involved with his beloved Yorkshire, but bitter arguments resulted and he can have derived limited pleasure from the continuing contact.

By 1997 Bairstow was in the grips of a depressive illness and a personal crisis. His second wife was undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer, but looking after the couple’s children without much assistance from him. Bairstow was drinking heavily and struggling with his business. In the autumn of 1997, on his way home from Wetherby races, he was involved in a car accident which left him with a metal plate in his right arm. He had long had problems with his hands, a legacy some said, in a way unkindly but with perhaps a grain of truth, of so rarely taking the ball cleanly. The combination of those difficulties prevented him from playing golf, his remaining relaxation. The accident also left Bairstow facing a drink driving charge and late in the year he took an overdose. He survived that, but on 5 January 1998 his wife found him at his home where he had hanged himself. The coroner, no doubt mindful of the previous equivocal attempt, suggested Bairstow’s actions might have been a cry for help, and returned an open verdict, but it rather sounds to me like this time he really had had enough. His Magistrates Court trial which, had the verdict gone against him, would inevitably have meant the loss of his driving licence, was due to be heard the following week.

One other reason sometimes put forward as a factor in Bairstow’s general malaise, although it seems improbable it could have contributed to his eventual demise, was the failure of his elder son, Andrew, to make the grade in the professional game. Andy, like his father a wicketkeeper/batsman, played three times for Derbyshire in 1995 but despite second eleven appearances for Worcestershire, Lancashire and Somerset he never found another county. He was a batsman first and foremost yet was given his chance by Derbyshire as a wicketkeeper. Given that the father so resented the attempt made to dictate to him what was his primary discipline it is perhaps understandable that he felt Andy’s failure all the more acutely on the basis he believed he had not been given a fair crack of the whip.

Jonny Bairstow, just 22, is another red-headed wicketkeeper batsman and, on reflection, I am struggling to understand why until recently I blithely assumed he was unrelated, although the 14 year age difference between him and Andy is doubtless the main reason. It is one of those things that once you know it seems blindingly obvious. The batting styles of father and younger son are similar, the difference being that Dad always looked like he relied on a good eye and brute strength as much as anything whereas the son, not that he is found wanting in the good eye and brute strength departments, has a fine technique. The Cricket Writers Club Young Cricketer of the Year for 2011 (and since 1950 they have picked only a handful of duds) has made a hugely encouraging start to his International career, and would seem to have the temperament to go with his ability. Andy Flower apparently said his ODI debut was the most impressive start he had seen by a young player, so he is clearly knocking on all the right doors.

I firmly believe, having watched the talented young man bat, and knowing whose blood is running through his veins, that Jonny Bairstow has a long and successful England career ahead of him. And for anyone who disagrees with me I say only this, to use a favoured phrase of Bluey, Stanley, David, Dad or whatever else you might want to refer to him as, You know three quarters of seven eighths of sod all!

Only so many ways to paraphrase “that was a bloody good read”, but it really was.

The Dylan referencing title gilds the lilly too. :wub:

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 19 January 2012