Tom Richardson – Surrey and England

Martin Chandler |

Tom Richardson’s glory years were the mid 1890s, during which period he set pace bowling records that for the next three quarters of a century, despite the fixture lists in England being largely unchanged since his heyday, were never threatened. They will certainly never be approached now. In an era when the concept of any bowler, irrespective of speed, taking 1,000 wickets in an entire career is an unrealistic one, to suggest the feat could be achieved in just four seasons simply beggars belief.

Contemporary posed photographs show Richardson in his early 20s as a strikingly handsome young man, over six feet in height, but slim and powerful. He was said to have the looks of a Meditteranean brigand, although certainly not the personality of one. Known affectionately as “Honest Tom”, he seems to have been remarkably affable and generous of spirit for a man who earned his living in the way that he did. Warwickshire and England wicketkeeper, Dick Lilley, who kept to Richardson in the 1896 series against Australia, wrote of him More than once, when he has been bowling on a fiery wicket, and happened to hurt a batsman accidentally, I have seen him start bowling wide of the wicket in order to minimise the possibility of again hitting the same player. With the possible exception of Brian Statham it is difficult to think of another fast bowler who would show that sort of compassion for a batsman.

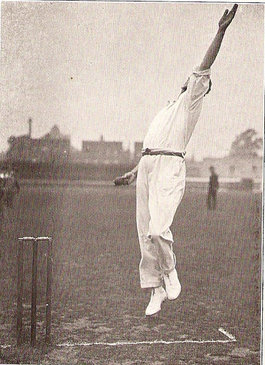

Inevitably there is no film of Richardson bowling, and it is many years since the last of those who saw him in action passed away. There are, courtesy of the photographic pioneer George Beldam, just a few camera shots of Richardson in action. One of these images accompanies this feature, but it should be borne in mind that by the time the iconic photographs were taken their subject was very much a veteran.

CB Fry, who was responsible for the text that accompanied Beldam’s images in their seminal work “Great Bowlers and Fielders – Their Methods at a Glance” described Richardson’s bowling thus;He bowled as fast at the end of a hard day?s work as he did in his first over. Great as was his pace, his deadliness consisted in his off break, which was very abrupt and startling. The extraordinary thing was that he could make the ball bite on a billiard table wicket on which slow and medium pace bowlers could not turn a hair?s breadth. His break was absolutely natural and came from the spin caused by his fingers sweeping across the ball as it left his hand, this sweep of the fingers being extenuated by a rather full turn of the wrist.

He took a long run, made a jump of his last stride but one, and delivered the ball with a very long and powerful swing. The whole of his body from his hips upward took part in the swing.

He paid little or no attention to variation of pace, and he owed nothing to deceptiveness of flight, either natural or artificial. His length was very accurate and he very rarely bowled a loose ball. He bowled to hit the wicket rather than for catches in the slips; he did not bump the ball down short.

In the same book I quote from above Dick Lilley confirmed that a wicketkeeper’s perspective was the same as that of Fry, a batsman; One characteristic of Richardson was the natural swing of the body that he put into his deliveries. No other fast bowler has possessed it to the same extent. To such purpose did he do this that he could make the ball swing right across the wicket. I have seen him pitch many a ball on the offside of the wicket and when I have taken it, standing back, it has been on the leg side.

To underline his remarkable perseverance Richardson’s Surrey and England teammate, Walter Read wrote, after he had taken his unheard of 290 wickets in 1895; It was the crowning proof of Richardson?s exceptional excellence that many of his finest performances were accomplished on wickets that afforded him little or no assistance; indeed, one scarcely knew whether to most admire his skill or his stamina.

By way of evidence to support Fry’s assertion that Richardson bowled to hit the stumps his statistics for 1893, his first full season, are illuminating. He took 174 wickets of which 104 were bowled. Remarkably that proportion was, by the time Richardson’s career ended, a few percentage points higher still.

As well as his stock delivery that came in to the right hander Richardson also possessed a fearsome yorker albeit one he used sparingly. He was once asked by Ranjitsinhji why he used this potent weapon so rarely. Ranji reported Richardson’s response as being …the extra yard, the extra effort, involved in sending down the yorker was too much for me if I wanted to last the season out

The great Australian all-rounder, George Giffen, provided an opponent’s view Other English bowlers are more subtle, but not one so deadly as Tom Richardson on a wicket that gives him the least assistance. By common consensus he was the finest fast bowler of his time, his only real competition for that title coming from his Surrey teammate Bill Lockwood. Further evidence of how highly regarded Richardson was by his peers comes from Lilley again; Surrey?s ranks became enriched with the most effective fast bowler of his generation and I have often wondered if a fast bowler of any other period has surpassed Richardson………. I have no hesitation in placing him as the world?s premier fast bowler who has played since I first had the privilege of coming into contact with all our first class players.

Was he the fastest? Probably not quite but those who saw them both felt his pace was only slightly less than that of the Essex amateur, Charles Kortright, and given that of those who saw both Kortright and Larwood bowl most felt Korty the faster, that means Richardson must have been genuinely quick. Kortright’s own view of Richardson was a simple one; The best bowler I ever saw.

For completeness the point should be made that both in 1892, when he made his debut for Surrey at the age of 21, and in 1893, there were mutterings about the legality of Richardson’s action most notably from the great Australian Billy Murdoch, who played against him once in 1892, and with him twice the following summer. There was never a complaint again and those who have written on the subject seem to agree that there was initially a problem, as there often is with fast bowlers when they strive for extra pace, but that by 1894 Richardson had ironed out whatever kink was initially present in his action.

Despite not having yet played a full season for Surrey Richardson made his Test debut in the third and final Test of the 1893 series against Australia. He was selected to partner Lancashire’s Arthur Mold, another fast bowler although, in Mold’s case, one who never managed to silence those who complained about his action. Although intended to play the role of junior partner in what was, most unusually in those days, an all pace opening attack, Richardson took five wickets in each innings. Rain on the first day meant that England did not have time in which to force victory but they were already 1-0 up and the series was therefore won.

Richardson was an automatic selection for the 1894/95 trip to Australia and, with 32 wickets at 26 runs each he played a leading role in England’s victory in the first truly memorable Test series. England triumphed by just 10 runs in the opening match of the series which was the first, and until Ian Botham’s heroics at Headingley in 1981 only, Test to be won by a side who had followed on. The second Test resulted in a slightly more comfortable England win before two thumping victories for Australia set up a thrilling climax. Despite all the momentum being with Australia, and the hosts setting a tricky looking fourth innings target of 297, England won comfortably in the end, by six wickets, due in the main to a major third wicket stand between two forgotten worthies, Albert Ward of Lancashire and Yorkshire’s John Brown.

In the series averages Richardson narrowly beat his opening partner, Yorkshire’s orthodox slow left armer Bobby Peel, to the top of the English bowling, but his performance was much more impressive than the bare numbers suggest. Firstly this was an Australian side where, save in the first Test when Ernest Jones was Australia’s last man, each member of the home team were competent batsmen. It should be remembered too that these were timeless Tests, played on superb batting wickets, and that on the one occasion when the Australian batting had real problems, in their second innings of the first Test, Richardson, as a pace bowler, was unable to use the sticky wicket. Surrey colleague George Lohmann said later of the conditions Richardson had to work with When there was no rain they were so good that it was impossible to get any work on the ball? it is a curious thing that on a perfect wicket a leg break bowler can get some work on the ball, but I have never seen an off break bowler who could do it except Richardson, and yet, fast as he is, they say he could get a spin even on Australian wickets. In my opinion he is the best bowler in the world on a good wicket? if he could only get a footing on sticky wickets his average would be about half what it is now.

The touring party got back to England just in time for the start of the 1895 season and, as was to be expected, Richardson was decidedly ring-rusty in his early performances. There were some who feared that the workload placed on him in Australia would exhaust him, so it is all the more remarkable that he went on to claim those 290 victims, at a cost of just 14 runs each. Two hundred wickets in a season is a memorable feat by any bowler, but the more so by a genuinely fast bowler. Arthur Mold managed 213 that same year, and had managed 207 the previous year. After that it was to be another 30 years before Australian Ted McDonald got 205. Of pacemen only Richardson has ever gone past 213, and he did so in three consecutive seasons. To further underline the Herculean nature of Richardson’s achievements in 1895 it needs to be borne in mind that on the whole it was a batsman’s season, this being the year of an Indian summer for a 47 year old WG Grace, who scored more than 2,300 runs including 1,000 in May, one of only three men who have ever accomplished that particular feat.

The following season was almost as productive for Richardson. There were 246 wickets at 16 in an Australian summer when he was instrumental in England winning the three match series 2-1. In the first Test at Lord’s a fast and true wicket promised a good match for batsmen, but Australia were undone by what was one of the greatest performances of Richardson’s career as he and his Surrey teammate George Lohmann shot the visitors out for just 53. Richardson’s share was 6-39, and he hit the stumps each time. Australia did rather better second time around but there were still five more wickets for Richardson and England won the match by six wickets. Honest Tom’s match figures were 11-173.

Richardson improved on that haul at Old Trafford as he played a lone hand for England with the ball taking 13 of the 17 Australian wickets to fall at a personal cost of 244, as Australia ran out winners by four wickets. A telling statistic is the extent to which Richardson was overbowled, as he toiled for 110 five ball overs altogether, 42 of them being bowled in a single unbroken spell in the second innings, as he made Australia work for their victory, more than 84 overs being needed to score the 125 required.

The deciding Test was at the Oval and Richardson was inevitably selected to play. In those days professionals were paid ten pounds plus expenses for a Test appearance and, noting the revenue generated by the matches, some decided their efforts were worthy of greater remuneration. Of the eight professionals invited to the Oval Notts’ William Gunn, and the Surrey quartet of Richardson, Lohmann, Tom Hayward and Robert Abel, made it known that unless they received twenty pounds they would not play. The other three, Lilley, Peel and Middlesex medium pacer Jack Hearne, feeling rather less secure in their positions, did not join in. The players were, of course, entirely justified in taking the stand that they did. By way of illustration of the point of the five amateurs in the side four received twenty five pounds each for their “expenses”, and the England captain, Grace himself, received forty pounds for his.

The professionals’ demands were, inevitably, rejected and Richardson, Abel and Hayward backed down quickly enough to play. Lohmann dithered and was omitted from the match but subsequently apologised for his conduct. Gunn, by this time not wholly dependent on his income from playing, stuck to his guns. Richardson, as we have seen an essentially genial man, must have been severely tested by the tensions created by the conflict of loyalties to his masters on the one hand, and his teammates on the other. As things turned out by the time of the next home series against Australia, in 1899, the professionals fee had doubled to twenty pounds per match, and Gunn did accept an invitation to play in one of the Tests. For Richardson however his Test career was, by then, in the past.

Returning to the Oval Test, that was a low scoring match won by England relatively comfortably. The dampness of the wicket and run-ups was such that Richardson, after all of his efforts in the first two matches, was called upon to bowl only six overs in the entire match.

In 1897 Richardson was almost as effective as in 1895 and his 273 wickets for the season at 14 ensured his place in the party that toured Australia that winter. He was just 27 and should have been entering his prime years. In fact his career path thereafter was on a downward curve.

England won the first Test of the series but lost the next four against what was a very strong Australian side. England’s bowling generally was a disappointment and, naturally, a great deal of work came Richardson’s way. He took 22 wickets, and was England’s best bowler, but this time he paid 35 runs each for his successes. He was unable to shift the first of the excess weight that was to affect him for the rest of the career, and in addition he was seldom totally free of rheumatic pain. Fry summed it up; Latterly his toil has begun to tell upon him; he has lost somewhat of his pace and devil, but whether he will recover it remains to be seen.It is a little ironic that his best figures of the series, and indeed of his Test career, 8-94, came in what was to prove his final Test – his efforts gave his side a first innings lead of 96, but the batsmen could not build on that sufficiently, nor his fellow bowlers provide him with the necessary support to enable that personal high to become a victory.

At least Richardson’s decline was not a sad one. He continued to play for Surrey regularly for another six seasons albeit now as a good bowler rather than a great one. The old zip was gone, but there was still guile and skill aplenty and while the great days were fewer and further apart than in his pomp, they still occurred from time to time. In 1899 Richardson was invited to Headingley for the third Test, although he was not selected in the final XI. In 1903, effectively his last season, he bowled as well as he had for years and it was therefore a surprise when, the following year, he dropped out of the Surrey side after just four Championship matches. He was still only 33. Even today some pace bowlers go on past that age, but for Tom Richardson it was not to be.

As did many former professional sportsmen in those days Richardson became a publican, first in Kingston and then the West Country. There was a plan that he would qualify by residence to play for Somerset but that seems to have been forgotten after one forgettable appearance for the county against the 1905 Australians. By 1907 he was back in London and the licensee of the Prince’s Head on Richmond Green.

The bare statistics of Richardson’s career remain remarkable. In four seasons he took 1,005 wickets and his eleven year career brought him 2,105 all told at 18. Amongst pace bowlers only Worcestershire’s Reg Perks and the great Freddie Trueman have also exceeded 2,000, and their careers extended over 21 and 20 years respectively. Very nearly two thirds of all his wickets were bowled, a remarkable statistic. Brian Statham, he of the “if they miss I hit” mentality could not quite get that particular figure up to 50%. One cannot help but wonder just how much more spectacular his figures might have been had Richardson played under the present LBW law – in his day the ball had to pitch in line as well strike the batsman in line before, of course, in the opinion of the umpire, going on to hit the stumps.

Much as he had earned it Richardson did not, sadly, enjoy a long retirement. In 1912 he took a short holiday in France where he collapsed and died whilst out walking. For many years, due to a combination of a lack of any first hand testimony and an ambiguous obituary in Wisden, it came to be accepted that he had committed suicide, but later research confirmed the cause of death was natural. In his youth both the Army and the Police Force had rejected applications from Richardson on the grounds of an abnormality of the heart – there was no post mortem carried out in France as there were no suspicious circumstances surrounding the death, so perhaps that old problem had finally caught up with Honest Tom.

Although the above is a natural point at which to conclude a feature about Tom Richardson the eagle-eyed will have noted that I have not yet made any reference to the writing of Sir Neville Cardus, with whose abiding impression of Richardson I will therefore conclude; His bowling was wonderful because into it went the very life-force of the man – the triumphant energy that made him in his heyday seem one of Nature’s announcements of the joys of life. It was sad to see Richardson grow old, to see the fires in him burn low. Cricketers like Richardson ought never to know of old age. Every springtime ought to find them newborn, like the green world they live in.

Great piece about a great bowler, Martin.

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am GMT 27 December 2011

Bit late on this, but thanks a lot for this, Martin. I enjoyed reading it over my lunchtime!

Wish there was a (300 page+) biography written about him.

Comment by Days of Grace | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012

As always – you must almost be sick of me saying so – a wonderful read.

Honest Tom is one of those cricketers that just seems to leap out from the pages of history – I remember reading of the two wonderfully conflicting accounts of the aftermath of his epic, in-vain, 13-wicket hall at Old Trafford in 1896. The romantic account was that he had to be assisted from the field by his teammates, slumped in their arms, so spent was he from his endeavours. The other is that after Australia had hit the winning runs Honest Tom bolted off the field, threw his boots to the ground and had sunk four pints before the rest of his teammates had even joined him!

That’s just one of many wonderful references – I particularly love Richardson’s response when he was asked what he thought of the increase in the number of balls in an over from five to six: “Give me TEN!” And when his great contemporary Bill Lockwood – never the most modest or self-effacing of men, by all accounts – was asked to measure himself against Honest Tom, he simply replied: “I wasn’t in the same street.”

The final quote from Cardus is apt as well, given that when Cardus selected his Six Giants of the Wisden Century in 1963 to celebrate 100 years of the publication, he chose Richardson as one of them. The other five were Barnes, Bradman, Grace, Hobbs and Trumper – so it’s fair to say he was in decent company.

Comment by The Sean | 12:00am GMT 6 January 2012