The Trouble With Ghosts …..

Martin Chandler |

A while ago I looked at the problems Jim Laker experienced after allowing a book to be published in his name without keeping a close enough eye on what his ghost writer was doing. The Lancashire and England medium pacer Cecil ‘Ciss’ Parkin, something of a latter day Sydney Barnes, had had a very similar experience almost forty years previously.

Parkin was born in 1886 in Eaglescliffe, County Durham, a village next to the border with the North Riding of Yorkshire. Always a fine cricketer Parkin played in a single County Championship fixture for the White Rose in 1906. It was subsequently reported to the MCC that Parkin had been born 20 yards into the Durham side of the border, Yorkshire were informed and, in keeping with their rigid policy, Parkin was never selected by the county again.

Despite that disappointment Parkin continued as a professional cricketer in the northern leagues. By 1910 he was with Church in the Lancashire League and, in the final summer before the Great War brought down the curtain on the First Class game he played half a dozen mid week matches for Lancashire with considerable success. He started with an impressive haul of 14-99 against Leicestershire.

When peace returned Parkin went back to the leagues, this time to Rochdale in the Central Lancashire League, but he played First Class cricket when he could and was selected for the Players in 1919. His haul of wickets when he did appear in big matches was such that he was selected to tour Australia with Johnny Douglas’ England side in 1920/21. In the event England had a wretched time, losing the series 5-0 and the return series at home in 1921 was little better as the English batsmen failed to get to grips with the menace of Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald. Parkin was one of the few Englishmen to emerge with any credit, taking 16 wickets in each series.

Finally, in 1922, by which time he was already 36, Parkin decided to embark on a full time career with Lancashire that was to last just over four seasons. Over those four full summers Parkin he took exactly 750 wickets at 16.68. The real surprise is that on the basis of such a short career in 1923, at a time when no county pro had ever published an autobiography, Parkin did so.

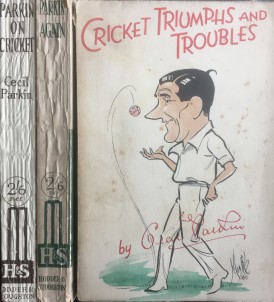

I have not been able to find out why Hodder and Stoughton, in those days a publisher primarily of religious works, chose to back Parkin on Cricket, but given that a mere two years later Parkin Again followed the first book it must certainly have enjoyed some commercial success.

Parkin on Cricket is not a long book, and it tells its author’s story in a concise and readable way. It is an interesting book in particular for Parkin’s explanation as to why he had spent so long in the leagues, and his views on the way players were remunerated and particularly the practice of the First Class counties in cutting their playing staffs adrift in the off season. His arguments on the subject are well articulated, and in many ways as relevant today as they were in 1923.

A shrewd operator where money was concerned Parkin’s book landed him a contract to write a weekly column for a Manchester based Sunday newspaper, the Empire News, and that is where, in 1924, his real problems started. There was a Test series in England that summer against South Africa, the first visiting Test side since the 1921 Australians. Selected for the first Test at Edgbaston Parkin watched his side score 438 before, in a remarkable collapse, Maurice Tate and England’s skipper Arthur Gilligan bowled the visitors out for 30, an innings that lasted just 12.3 overs.

England, unsurprisingly in the circumstances, won the Test by an innings, but the South Africans batted very much better second time round and came with 18 runs of making their hosts bat again. In that innings Parkin’s services, on the face of matters surprisingly given he was riding high in the national averages at the time, were not used until fourth change. In an innings that lasted for as long as 143.4 overs Parkin bowled only 16 of those, and went wicketless.

The wicket at Edgbaston was a hard one, and Parkin’s real strength was on softer, slower tracks and, particularly, the ‘sticky’ wickets that used to be encountered in the days before pitch covering became the norm. Conditions were not therefore right for Parkin, but whether or not he was upset at the time it would not have amused him when, amidst the banter in the Lancashire dressing room at the next county match, he was asked about his initial selection with the question; “did tha’ get picked for tha singing?”.*

During the game a cable arrived for Parkin from the Empire News, wanting to know where the copy due from him for that week’s column was. Knowing that he would not have time to produce anything in time Parkin asked one of the Lancashire journalists to put something together for him and send it through. It is, despite what Parkin subsequently said, inconceivable that there cannot have been any conversation between the pair about what the column might contain. What was written in Parkin’s name was to cause a sensation:-

On the last morning of the Test match there were 105 minutes play. With Catterall hitting so finely it was necessary for the England captain to make many bowling changes. During those changes I was standing all the time at mid-off, wondering what on earth I had done to be overlooked. I can say that I never felt so humiliated in the whole course of my cricket career. Nothing like it has ever happened to me in First Class cricket.

I admit that on Monday I was not at my best, but why should Mr Gilligan have assumed that I would be worse than useless on Tuesday? It has been said that the wicket was too hard for me. In that case, why was I ever played at all? A First Class bowler with any sort of reputation has that reputation to keep, like anybody else.

I can take the rough with smooth but I am not going to stand being treated as I was on Tuesday. I feel that I shouldn’t be fair to myself if I accepted an invitation to play in any further Test match. Not that I expect to receive one.

The Cricketer, edited of course by the ultimate establishment man ‘Plum’ Warner, thundered loyalty to one’s captain and one’s comrades is the beginning and end of a cricketer’s creed, and when we find an England player so grossly infringing every rule of courtesy, common sense, and discipline, it is surely time to enter the strongest possible protest.

To be fair to Warner he did not ignore views that conflicted with his own, and a letter was published from a man who would appear to be an Oxford don two weeks later, in which the opinion expressed was; he (Parkin) was treated with gross unfairness by the captain … and I consider that he was justified in feeling a great grievance. As the story featured regularly in the magazine’s correspondence pages for the rest of the season however the writer of that letter, a Mr RP Dewhurst, seemed to be in a minority of one.

Parkin was furious when he saw the article that appeared under the headline Cecil Parkin Refuses to Play For England Again. He came out straight away and issued a statement, drafted with the assistance of his county captain, Jack Sharp, denying that the article was written either with his authority or containing what he really thought. He wrote a personal letter of apology to Gilligan, which the latter accepted without hesitation. But Parkin never did name the journalist concerned. He did not, of course, ever figure in the selectors’ discussions again and, disenchanted with county cricket, he was back in the leagues before too long.

In the circumstances it is hardly surprising that in 1925 Hodder and Stoughton were happy to publish Parkin Again, although there is nothing particularly contentious in the book. It is a mixture of Parkin’s thoughts on playing the game, on current players, and a look forward to the visit of the 1926 Australians. One contemporary reviewer described Parkin as a mixture of buffoon and serious philosopher who seems to be unable to open his mouth without putting his foot in it. But Parkin deliberately steered clear of the Gilligan controversy of the previous summer and was keen to ask his reader to take all that I write in a spirit of fun.

As his performances in 1924 demonstrated Parkin was still a fine bowler and, had his article not been published, he would in all probability have gone with Gilligan’s party to Australia for the 1924/25 Ashes. As it was he stayed in England and continued to write his column at one stage making the point that if a sufficiently good amateur could not be found for the captaincy of England that a professional such as Jack Hobbs should get the job. In the 1920s this was an incendiary remark as far as the cricketing establishment were concerned and Lord Hawke bit, making his famous Pray God may no professional ever captain England remark.

Parkin played on for Lancashire through 1925, his benefit season, and now in considerable demand as a columnist in November 1925 he signed up to write exclusively for the Topical Times. Despite the exclusivity clause in his contract on two occasions his employers, Dundee based DC Thomson, had cause to complain about other publications using Parkin’s name. The first time, when a monthly magazine was involved, they let it pass, but commenting on an Ashes Test in a Sunday newspaper was different and, when the best explanation Parkin could come up with was that the offending column was an interview rather than his writing anything, Thomson’s decided court action was needed. With the benefit of legal advice Parkin realised his position was untenable, and he gave an appropriate undertaking and agreed to pay Thomsons’ costs.

In the 1925 season, and given the distraction of his benefit, Parkin’s return of 152 wickets at 19.30 was respectable enough, but he was falling out of love with the game and after just fourteen matches of the 1926 season he sought and was granted a release from his contract with Lancashire. Parkin went back into the leagues where he continued to play professionally until 1935. A year later his third and final book appeared.

It could not have been made more clear than it was in Cricket Triumphs and Troubles that Parkin much regretted the events of 1924, a message which would only have been brought home to him harder by the warmth of the foreword that Gilligan agreed to contribute. It was the first time he had taken the opportunity to set out his clearly heartfelt, but still not entirely convincing, account of the events of 1924.

In later life Parkin was the avuncular host and licensee at a Manchester Hotel, but he rapidly put on weight after giving up the game and died of throat cancer at the relatively early age of 57 in 1943. He was cremated and his Ashes scattered on the wicket at Old Trafford, the scene of so much of his success.

*Parkin was known as something of a jester, always trying to entertain the crowds and his fellow players and one of his habits was to sing popular show songs as he walked back to his mark.

Leave a comment