The Story of a Famous Draw

Martin Chandler |

There were a couple of Ashes Tests there in Edwardian times, and a couple against South Africa in the 1920s, but the modern Edgbaston only became a regular Test venue in 1957 when, after half a decade of development financed largely by a successful football pool venture, the revamped ground played host to the first of a five Test series against West Indies. The game ended as a draw, but fortunes ebbed and flowed through the course of a match which demonstrates as well as any why a definite result is not an essential ingredient of a memorable Test match.

The two countries had contested three series since the war. The first of those was in the Caribbean 1947/48 when England, failing to learn the lessons of their two pre war visits sent an understrength side and lost the four Test series 2-0. Three years later the West Indies came to England to face the first team. They were expected to lose, but comprehensively and deservedly defeated the full might of England 3-1. Any doubts about the islands’ ability by then answered England took the best they had back to the Caribbean in 1953/54. When the home side won the first two Tests comfortably it seemed the series was going to be a humbling experience for Len Hutton’s side, but thanks in large part to the captain’s own efforts two of the remaining three matches were won meaning that, with the fourth Test being drawn, the series was squared.

Since then the West Indies had played just twice. They had lost heavily at home to Australia in 1955, a few weeks after Hutton’s side had demolished the Australians, and undertaken a tour of New Zealand the following year. Little could be deduced from that contest however as the visitors sent a very young and inexperienced team.

By the mid 1950s English cricket was in rude health. Three consecutive Ashes series had been won and if the previous winter’s visit to South Africa had been a little disappointing, the home side narrowly taking the fourth and fifth Tests to cancel out thumping England wins in the first two matches, England supporters were happy enough.

The first four tour matches were all won by the West Indians, before the English weather brought a series of draws for the tourists. They never looked like being defeated however, and had Yorkshire hanging on a week before the Edgbaston Test, so West Indian confidence was high.

On paper the West Indies team was immensely strong. It contained all three of the famous ‘Ws’, Frank Worrell, Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott, but all three were much nearer the end of their careers than the beginning. Two other all time great batsmen were also playing, Rohan Kanhai and Garry Sobers but they, and the tragic ‘Collie’ Smith, surely destined to join them but for that 1959 road accident, were all lacking in experience. The one batsman whose name means little today was opener Bruce Pairaudeau.

The bowling was led by the wild but very quick Roy Gilchrist, backed up by the medium pace of Worrell and two all-rounders, skipper John Goddard and Denis Atkinson. The spin attack was led by the mercurial Sonny Ramadhin who, along with Alf Valentine, had been responsible for England having such a torrid time in 1950. ‘Val’ was only 27 but, not having ever really been the same bowler since 1950, did not make the side. There was another great cricketer in the West Indies party, but Wes Hall was only 19 and was not picked for any of the Tests.

England were led by Peter May, a successful skipper since 1955 and a batsman of undoubted class, although on a personal level he had had a miserable time in South Africa, averaging just 15.30 with a solitary half century to show for his ten innings. Against that background a good deal of responsibility was expected to fall on Colin Cowdrey. England’s other batsmen were Peter Richardson, Brian Close and Doug Insole. Richardson, at the time briefly looked a class act and has a decent record, but neither Insole nor Close ever scored heavily in Test cricket.

The home side’s real strength was in its bowling. Fred Trueman and Brian Statham led the attack, with Trevor Bailey as first change. The spin department was in the capable hands of the Surrey pairing of Jim Laker and Tony Lock. The vastly experienced Godfrey Evans kept wicket for England. Kanhai donned the gauntlets for West Indies.

The sun was to shine on Birmingham throughout the match. The ground was full and the atmosphere intense but friendly, a West Indian steel band being allowed to set up and provide some off field entertainment and encouragement for their countrymen. Amidst the huge levels of anticipation in the capacity crowd May won the toss and, to the surprise of no-one, chose to make first use of what looked like a beautiful wicket to bat on. England would have felt they just shaded the first session. Gilchrist had Close caught behind the wicket and Ramadhin bowled Insole but at 93-2, with Richardson firmly established and May having played himself in after a tricky start against Ramadhin all seemed to be well. At lunch Ramadhin’s figures were 1-11 from twelve overs, figures clearly demonstrating the lack of trust the batsmen had in their ability to pick which way the ball would turn.

After lunch English optimism evaporated as Ramadhin produced a remarkable spell of bowling. The batsmen seemed becalmed and in the first half hour of the afternoon Richardson could add only three to his score before turning Ramadhin into the safe hands of Walcott at short leg. May then seemed to decide that Ramadhin had to be hit out of the attack and that, as captain, the responsibility of doing that fell on him. He drove him through the onside for one boundary, but in trying to repeat the treatment succeeded only in giving a catch to Weekes at midwicket. Two runs later the famous forward defensive of ‘Barnacle’ Bailey proved no barrier to Ramadhin. An over later a rather ugly cross batted shot from Lock meant he was bowled as well. May cannot have been happy at his county colleague who, presumably, he had sent in above Evans due to concerns that the ‘keeper’s usually carefree style was not what was called for whilst Cowdrey remained at the crease. The last specialist batsman was not there for long though, and in benign conditions England had slumped from 104-2 to 121-7 when, seemingly adopting the same tactics as his captain, Cowdrey was caught by Gilchrist at cover.

It might have been expected at that point that Laker and Evans would have sought to have a look at the bowling, but it was not to be, Laker leaving Ramadhin with figures of 7-22 after he was bowled, perishing after essaying an ugly slog at a good length delivery. England were all out by tea, but the tail did wag and the last two wickets added 56 to see them close on 186. The main contributor was Trueman, ably assisted by his new ball partner Statham, and to the extent that he ended with 7-49 the pair put something of a dent in Ramadhin’s figures. For a man who was a more than capable hard-hitting lower order batsman Truman has a remarkably disappointing record with the bat in Tests and his 29 was, in his twelfth Test, his highest score to that time. There were 55 more Tests for Truman in the years to come, and he got into the 30s several times, but never beyond – a strange record for a man whose First Class career produced three centuries and 26 fifties.

If anyone watching the game had any concerns about the pitch those would have evaporated as the evening session unfolded. Trueman did bowl Pairaudeau with just four on the board to raise English spirits, but by the close Kanhai and Walcott, seemingly untroubled by any of the English bowlers, had taken the score to 83-1. Day one most certainly belonged to the visitors.

From the very first delivery of the second morning Statham won an lbw decision against Kanhai which brought Weekes out to join Walcott. Not long afterwards Walcott went for a quick single and as he completed the run fell to the ground in obvious distress. After assistance from the English fielders he managed to get to his feet and carry on, but he was in some discomfort from what was clearly a more than trivial leg strain and it was not long before he signalled to the pavilion for a runner. Pairaudeau came out for what was to prove a long day for him. Walcott was the second Barbadian to fall victim to a leg strain in the match. Worrell had left the pitch the previous day with a similar injury and like Walcott was unable to field again in the match.

Despite his restricted mobility Walcott still outshone Weekes and it was the latter who was next to go, bowled through the gate by Truman for 9 after the pair had added 37. Weekes’ dismissal brought the entry to Test cricket in England of Sobers. When the score had advanced to 138, at which point England might still have had a way back, Sobers went for an impossible single and should have been run out by yards. Unfortunately for England however Cowdrey did not realise he had as much time as he in fact had and his throw on the turn to the bowler’s end was too high, and gave the 20 year old the precious moments he needed to get back to the safety of his ground. May’s tactics were clear. If he couldn’t get the batsmen out he wanted them contained. Prior to lunch Bailey bowled eight overs for three runs, and Laker six for six.

After lunch Sobers, to an extent, broke free of the shackles before, just short of England’s total and ten short of what would have been a deserved century, Walcott was caught by Evans from Laker’s bowling and he departed with Pairaudeau. If Sobers had been dismissed first, and not too long afterwards at 197 he was, the crowd would have been treated to the sight of Worrell coming to the wicket with a runner of his own and all the potential for comedic moments that that would have brought to proceedings. As it was poor old Pairaudeau had just enough time to have a cup of tea before he went out for his third spell at the crease.

Sobers had got to 53 when he was dismissed, superbly caught by Bailey who, in the style of the 21st century, had to dive to his right to take the ball inches from the ground at second slip, but after that dismissal nothing went right for England and three hours later the close came with Smith 70, Worrell 48, and the lead 130. There had been the odd close call, Trueman failing to cling on to what would have been a remarkable caught and bowled from a return drive by Worrell, who was later beaten all ends up by a leg stump yorker that somehow contrived to miss its target by the proverbial coat of varnish. At the other end May put down Smith from the bowling of Bailey, but it was a very difficult chance as May ran hard from mid on with his back to the wicket. Day two again belonged emphatically to Goddard’s men.

Saturday dawned bright and sunny again, albeit with a breeze to spoil the spectators comfort just a little. The West Indian contingent in the crowd was swollen by those whose employment had prevented them attending on the Thursday and the Friday and the gates were shut before play even began. The pattern continued as before, May looking to save runs where he could and keeping Trueman and the new ball back. Eventually, ten overs later than he might have done, he decided to take the cherry in the hope that his strike bowler could knock over Smith, by then well into the nervous nineties. As was his wont Truman started off with a bouncer first up, and Smith hooked it to the boundary to go to 101 – a potentially interesting confrontation had gone the shortest possible distance.

England finally tasted success on the stroke of lunch when Statham bowled Worrell. Following the break it was skipper Goddard who came out with Smith, and this pair added 79 to take the score to 466 before, at last, there was a clatter of wickets to Laker and west Indies were bowled out, just before tea, for 474. Smith had batted twenty minutes short of six hours and scored 161, with a six and 19 fours.

After the interval England had a deficit of 288 to deal with, and they got to 63 before substitute fielder Nyron Asgarali held a difficult chance from Richardson at backward short leg from Ramadhin. For Insole Ramadhin was still too difficult to pick and he was soon bowled for a duck in what was to prove his last innings in Test cricket, but after that May and Close looked secure enough as they took England to 102-2 at the close. The honours on day three were trickier to call, but on balance West Indies had probably shaded it. One has some sympathy with the sub-editor who chose West Indies Attain Impregnable Position as his Sunday newspaper’s back page headline, but he must have felt a little foolish come Tuesday evening.

Sunday was a rest day and, when the game resumed on the Monday the breeze was absent. It was strictly shirt sleeve order for the 20,000 or so present and they saw an early West Indies breakthrough when, as in the first innings, Gilchrist caught Close’s outside edge. The only difference from Thursday was that the catch went to Weekes at slip who held on despite Kanhai starting to go for the catch. Thus it was that Cowdrey joined May with England still 175 in arrears. The sun stayed out all day, and so did May and Cowdrey, and at close of play the deficit was gone and England had the security of a lead of 90, still with seven wickets in hand.

At times, particularly before lunch, it was slow going. Ramadhin bowled five successive maidens at one point before lunch and his partner in parsimony, Atkinson in his alternative off break mode, was almost as ‘successful’ managing four. Ramadhin bowled 20 overs before lunch, 12 between lunch and tea, in which time the new ball was taken, and another 16 after tea. His figures for the day were 48-20-74-0, remarkable figures on their own, the more so given that this was the fourth day, and that on the first this mercurial spin bowler had taken 7 wickets in 31 overs.

What happened? May and Cowdrey had both acknowledged that they could not pick Ramadhin’s leg break, so they decided to treat every delivery as an off break and stretch right forward with bat and pad together or, more often than not, with bat tucked behind pad. In these days of DRS they would doubtless not have got away with it, but appeal after appeal for lbw was turned down, umpires Dai Davies and Charlie Elliott clearly deciding that the step forward was enough to grant immunity – the West Indians view was that the pair were playing Ramadhin with their pads and simply kicking the ball away, but whether the umpires shared that view or not they weren’t going to give the Englishmen out.

There was more bad news for West Indies after tea as Gilchrist, who had been troubled by an ankle sprain all day, had to give up and retire to the pavilion to join Walcott and Worrell on the treatment table. So there was no discernable West Indian pace attack for the final day – at this point in his career Sobers’ only bowling style was his orthodox spin. Despite the accusations of negative play, understandable in light of the match situation, England still made 276 in the day so whatever may have been said or written there was undoubtedly plenty of stroke play as well. At the close May had 193 and Cowdrey, who happily played second fiddle throughout, 78. Day four most certainly one for England.

Overnight the weather deteriorated and there was some rain and a forecast of more to come but, despite a few early showers, the dryness of the ground quickly soaked up the rain and an initially sparse crowd saw a prompt start. Before lunch May and Cowdrey added 89. There was little batting to come, so they took no chances and West Indies, two bowlers down of course, showed little ambition and the cricket at this stage was rather less than exhilarating. The score at the interval was 467-3, with May on 231 and Cowdrey 124.

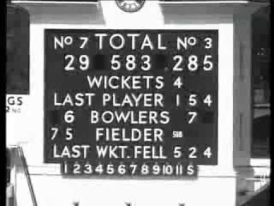

Early in the afternoon session May actually gave a chance, although not much of one as Smith could do no more than get a hand to a ball that came towards him at deep midwicket at great pace. There was some consolation for Smith when it was he who finally claimed Cowdrey’s wicket when he had him caught in the deep by Asgarali after a booming drive. By now England were safe and Evans came out for 27 minutes in which he and May added a rapid 59. On 278 May might have been caught at square leg from a fierce pull. He was fortunate that the substitute fielder he picked out, future captain Gerry Alexander, was a wicketkeeper by trade and he failed to make the catch. May had advanced to 285 when he finally decided to call it a day and declare with England on 583-4. West Indies therefore needed 296 in two hours fifty minutes, an impossibility of course, and some pedestrian cricket was expected.

Trueman struck early in the West Indies second innings, luring Kanhai to his doom with a bouncer. The youngster hooked and Close took a fine running catch on the fine leg boundary. Soon afterwards the same bowler struck Pairaudeau on the body with what was described as a fast full toss – had Gilchrist delivered it the word ‘beamer’ would doubtless have been used. Later in the same over Pairaudeau fell victim to a Trueman yorker and when Sobers, after a brief flurry of boundaries, nicked one to Cowdrey in Lock’s leg trap the visitors took tea a little anxiously at 26-3. After tea the tension ratcheted up several notches as the two invalids, Worrell and Walcott, soon departed in the same manner as Sobers, one each to Lock and Laker.

West Indies were in deep trouble as Smith joined Weekes. In the half hour they were together nerves began to settle. It was grim stuff from Smith, who showed no ambition beyond survival. The experienced Weekes looked happier as he advanced to 33 but, unexpectedly, it was he who was next to go and rekindle England ambitions. He was caught at slip by Trueman from Lock’s bowling.

With forty minutes to go Goddard joined Smith. He was unbeaten at the end, and had still not opened his account. He survived numerous lbw appeals by adopting the same tactics that Cowdrey and May had utilised so successfully against Ramadhin. Lock in particular was less than happy, his appeals becoming more and more stentorian as West Indies inched towards safety. Smith hung on grimly with his captain, although at one stage he could not resist the temptation to try and drive Laker for six. May got both hands to the ball at deep mid on but could not hold on. When Smith was eventually lbw to Laker, after 64 minutes in which he scored just five runs, West Indies had avoided defeat. There was just enough time left for one defiant boundary from Atkinson before a mightily relieved Goddard claimed the draw. His side ended on 72-7. Day five firmly to England as well, even if they couldn’t quite get over the line.

Should May have declared earlier? On Cowdrey’s dismissal? Probably, but there can be no guarantee that West Indies would have batted the same way if they had had to face another dozen overs, and despite the short time remaining England still got 60 overs in. In fact the whole five days produced 580 overs – six and a half days of play at modern rates. Of the many records set in the match most have now been beaten. May’s record score for an England captain was taken by Graham Gooch in 1990, and his and Cowdrey’s record fourth wicket stand was overhauled by Mahela Jayawardene and Thilan Samaraweera in 2009. One does remain however, and is unlikely to be bested any time soon – Ramadhin’s 774 deliveries in the match.

Leave a comment