The Old Bald Blighter – Part III

Martin Chandler |

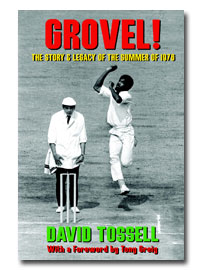

Thirty years on David Tossell wrote the story of the 1976 West Indian summer. His account of “that session” is a modern classic and a fitting conclusion to Brian Close’s story.

Although 1976 is remembered as the year that West Indian dominance of the game began the first two Tests in the series were draws, and in the second in particular England secured a moral victory as the game ended with the tourists on 241-6, still 81 short of their target, and with all their specialist batsmen back in the pavilion.

The first Test was notable for a 24 year old Vivian Richards’ first Test double century as West Indies piled up an unassailable first innings total of 494. England conceded a first innings deficit of 162. Brian Close failed but David Steele, who finally got the Test century he so richly deserved, and an inexperienced Bob Woolmer were at their most obdurate and the match was deep into its fourth day before the tourist began their second knock. They scored at almost five an over to leave England what proved to be 78 overs to negotiate and at 55-2, with more than three hours to go and the talismanic Steele, for the first time in his Test career dismissed cheaply, they were looking just a little rocky before Close and John Edrich calmly batted out time with a century partnership.

Moving on to Lord’s Greig won the toss and chose to bat and England eventually got to 250 with Close top scoring. In the afternoon session, for a time, the nation dared to hope that 27 years after his Test debut Close might finally record the Test century that had always eluded him, but it was not to be as on 60 he drove a full toss from left arm spinner Raphick Jumadeen into the hands of Vanburn Holder at extra cover.

In the tourists reply only Gordon Greenidge and Clive Lloyd made any impression as England gained a precious lead of 68 which they had extended, without loss, to 95 at the end of the second day. Sadly the third day was lost to the weather and in a curtailed fourth day England ground on towards safety, Close scoring 46 out of a stand of 83 with Steele. After England were finally dismissed on the fifth morning it looked, with the tourists on 230-2, like a dull draw but West Indies then lost four wickets in the last 40 minutes and while England were never in with a chance of winning Greig had a few overs in which he could pressurize the West Indian batsmen and he made the most of it.

The third Test was played at Old Trafford. West Indies won the toss and batted and a fairytale seemed to be unfolding. Debutant Mike Selvey took three wickets and Mike Hendrick another as West Indies slumped to 26-4 – it should have been five but Alan Knott called for and just failed to hold a steepling edge that Greenidge put up – if only he had left it to Derek Underwood at fine leg it would have been a comfortable catch. The cost of the mistake is reflected in the 134 that Greenidge scored out of 211.

Englands reply, Close being sent in to open with Edrich, was a disaster as they collapsed to an ignominious 71 all out. Worse followed as the West Indians seemed to bat for the second time on a different wicket as they amassed 411-5 before the declaration came. England were left to bat out time or score 552 for victory. Strangely no account of the tour was published at the time, and it was therefore 2007 before David Tossell’s “Grovel” magnificently reconstructed the tour. He has kindly agreed to allow CricketWeb to include in this feature his account of what happened next:

At ten minutes past five, John Edrich and Brian Close – combined age of 84 followed the West Indies players to the field to begin 80 minutes that would go down in Test match lore. Mike Selvey sets the scene by recalling the heightening tension that had wrapped itself around the day’s play and the unsettling, sinister, feeling that something was about to blow.

‘You have to understand the atmosphere during that game. It was a very hot summer and that day it was very oppressive. It wasn’t a blazing hot day, but it was steamy. There was a really heavy, over-burdening atmosphere by the time Saturday came around, with storms threatening. All day there had been this incessant noise from the crowd, cans banging. This rhythm going all day, all day. It started to get to you and I am pretty sure it got to the West Indies bowlers as well. It was mesmeric and quite threatening. You could feel it winding down into you, this noise, and they got carried away with it.’

The first ball of the innings, bowled by Andy Roberts from the Stretford End, was a short one. Edrich soon escaped to the non-striker’s end by taking a single and, two balls later, Close was swaying to safety. Roberts had made his intentions clear and the West Indies fans, imbued with the spirit of conflict, were quick to respond. As the Antiguan stared down the wicket and began his approach to the crease, the din rising into the Manchester evening was more reminiscent of a big European match at the football ground down the road. Close, his concentration diverted, pulled away from the wicket, halting the bowler’s run. The crowd howled, interpreting the batsman’s action as cowardice on the front line.

No one would seriously be able to level that accusation at Close as events unfolded over the next hour or so. The tone had already been set by Roberts and what would follow prompted John Woodcock, writing in The Times, to say that he had never felt as close to seeing a death on the cricket field. Alex Bannister of the Daily Mail would describe it as ‘the type of attack that should be outlawed before a victim is killed or maimed for life’. Another renowned writer, Frank Keating, spoke of ‘sadistically terrifying head-hunting’.

The West Indies bowlers, notably Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel, performed as if their single intention was to humiliate and, quite possibly, injure the England batsmen. Ball after ball flew past the ears or bit into ribcages. The cracked pitch simply compounded the peril in which Close and Edrich found themselves, making it impossible to judge the height of each assault. Close, as he had done at Lord’s 13 years earlier, stubbornly stuck his 6 ft 2in. frame in the way of everything. At one point, he was staggered by a Holding delivery that hit him in the lower part of the chest, his legs buckling like a 1970s British heavyweight. One blow even cracked his box, at which point the anger of Edrich at the umpires’ reluctance to intervene could clearly be seen. The bowlers seemed more interested in challenging Close’s renowned bravery, pounding him into surrender, rather than taking his wicket.

Pat Pocock remembers, ‘Greig had said he wanted Closey in as a battering ram and that was exactly what he was. He was pummelled. He didn’t have the technique to play Test cricket at that stage; he just had the most guts of anyone who had ever walked on a sports field.’

Holding’s first over had concluded with a yorker that Edrich dug out, followed by a delivery that shot along the ground. Those two balls had sent the crowd even closer to delirium, forcing Lloyd to take the unprecedented action of venturing to the boundary to ask his own team’s fans to lessen the volume of their support. Close pushed a single into the covers off Roberts to get off the mark.

Things took a decidedly nasty turn when Daniel was thrown the ball. Perhaps the sight of Holding hitting Close with the last delivery of his third over had increased the rate of adrenalin pumping through him; or maybe the crowd, as Selvey suggests, had got into his veins. Daniel was wild and dangerous. is first missile, called as a no-ball by Lloyd Budd, steepled past Edrich’s head. So did the third, another no-ball. The next one was legal, necessitating more evasive action, before Edrich was struck on the pads and then beaten by pace. Another no-ball made it a nine-ball over, which must have felt like purgatory for Edrich.

Holding’s response was a desire to prove to Daniel that it was he who was the biggest, baddest bowler in town, firing two short balls past Close’s torso. The pattern of Close taking Holding’s overs had been established, largely because the batsmen were simply unable to find a way to rotate the strike with singles. After 37 minutes’ batting, they had scored only one run each in a total of 8 for 0. Perhaps out of sympathy for them, the twelfth men emerged with drinks. Daniel’s second over to Edrich mirrored the first – three short balls, two no-balls, two air shots by the batsman. Holding bowled a relatively uneventful maiden to Close before Roberts returned and, to widespread astonishment, was driven to the boundary by Edrich.

With the innings approaching the hour mark, Holding began his sixth over by beating Close outside the off stump. Second ball: bouncer. Third ball: bouncer. Fourth ball: pitched up just enough to hit Close a painful blow in the ribs. Umpire Bill Alley looked like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, bemused and helpless at the centre of the tornado swirling around him. If only he’d had the heart to do something about it. When the fifth ball was dug in short the big Australian was at last stirred into action, delivering a warning to Holding. It was the first time an umpire had issued a public reprimand for ‘intimidation’ in the previous 18 months of Test cricket, which perhaps explained Alley’s reluctance to step in. Sixth ball: Close struck in the ribs.

‘That night was the biggest umpiring disgrace I have ever seen,’ says Pocock. ‘To allow things to go on like they did was sheer lunacy. I think the fact that Lloyd Budd was in his first Test was a very important factor because he didn’t want to rock the boat. Bill was more senior so if he didn’t think they were overdoing it, Lloyd was not going to stick his head above the parapet.’

Holding, as you would expect, believes the umpires acted properly, arguing, ‘We bowled too short, but we didn’t bowl bouncers. The batsmen got hit because it was a bad pitch. If we were bowling bouncers they would have been able to get out of the way.’

However, fellow fast bowler and Sky Sports commentary colleague Bob Willis, writing in Cricket Revolution, would call it ‘the most sustained barrage of intimidation’ he had seen. He remains firmly of that view, pointing to the fact that the International Cricket Conference’s annual meeting in 1975 had made no specific reference to the height of deliveries when discussing at what point ‘persistent bowling of fast short-pitched balls’ constituted intimidation. ‘Mikey and his colleagues wouldn’t agree with my view,’ Willis states. ‘He would say that those tactics are legitimate; that if you are not bowling bouncers, that if you are bowling the ball in the rib area, then that is legitimate. Now, I think the laws are fairly straightforward about

intimidation.’

Around the Old Trafford arena, the X-rated action on the field and a day’s worth of beer was causing the odd scuffle to break out on the boundary. The mood was lightened when a fan ran to the centre of the ground and offered Edrich a huge home-made bat, double the width of his wicket.

Meanwhile, a funereal silence had gripped the England changing-room, where the side-on view laid out the horror of the ordeal facing Edrich and Close far more vividly than the behind-the-arm perspective of the TV cameras. Even Tony Greig, who usually hated watching the play before he went in to bat and could easily fall asleep on a bench right up to the moment of leaving the pavilion, was transfixed by a morbidly compelling passage of play.

Mike Selvey insists that any fear that might have existed was concealed. ‘I never felt anyone was scared,’ he says. ‘I don’t recall players saying, ‘Fuck me, I don’t fancy that.” Even so, Bob Woolmer, standing on the balcony, was in for a shock, thanks to what Steele describes as ‘a marvellous migraine’. Steele says, ‘It wasn’t because I was shitting myself – it was the noise during the day. The tom-toms were going and I was down on the boundary all day. I told Greigy I had a splitting headache and said, ‘There is no way I can bat with this bloody thing.’ Bob was on the balcony, thinking he was not going to get in, when he got the hand on the shoulder. I said, ‘Mate, I will do you a favour one day,’ to which he replied, ‘I hope I live to see the day’, and went to put on his pads.’

Woolmer admits that ‘nobody was anxious to follow [Close and Edrich] to the crease’ and recalls his promotion in the order. ‘For the first time I experienced a cold sweat. The more I watched the two old-timers, the less I wanted to go in. I was freezing cold.’

Greig continues, ‘I remember going out to the toilet at the back of the dressing room and seeing Derek Underwood, who was one of our night-watchmen. He said, ‘Listen, I haven’t made a run, I am struggling with the bat, I don’t particularly want to go out there today.’ This was about half an hour before the close of play. He had been watching and there was no way in the world he wanted to go out there.’

Over time, and in the confusion of events, the issue of who was handed that unenviable task has become clouded. While Greig recalls asking Underwood and Pocock to prepare to bat, Selvey also remembers having his pads on by the close of play. Pocock, who describes the 80-minute passage of play as ‘the most appalling and unforgivable that I ever saw in all my years in first-class cricket’, remembers privately urging Close to swallow his pride, save himself and retire hurt. ‘How I didn’t get in, I will never know,’ he says.

It was the most frightening Saturday evening programming BBC viewers had witnessed since the last time they’d peered from behind their sofas to watch the Daleks attempting to exterminate the universe. One of the viewers was Barry Wood, who knew that it could have been him ducking for his life in Manchester if events at Lord’s in the second Test had gone differently. Wood had woken up after a minor operation on his knee and switched on the television to see Close and Edrich diving for cover. His first thought was that the BBC was showing an edited sequence of bouncers. It took a few minutes to realise that the action was being broadcast live. ‘I was sitting up in bed ducking and swaying. I couldn’t believe they were bouncing every ball past our lads’ noses.’

Selvey continues, ‘It was an incredibly brave performance. These two old boys, England’s oldest opening pair, refusing to get out. I can’t speak too highly of Closey that night. Everybody, myself included, used to regard Closey as a bit of a joke, a caricature. He was mad. I don’t mean that in a derogatory way, but you heard so many stories about him and I have played in games where you have seen these things that have now become legend. I was batting against him when his feet got so sore that the blood ran out of the eyelets of his boots. I had seen it. I knew he was mad. I had heard stories about him from Allan Jones, my bowling partner at Middlesex, from his time at Somerset. But what we saw then was an extremely brave man. He went up massively in my esteem, as did John Edrich.’

The arrival of Padmore into the attack defused the situation to a small degree. The off-spinner might have modelled his action on the great Lance Gibbs, but there all similarity ended and his introduction offered safe haven for the batsmen at one end. West Indies skipper Lloyd, these days one of the world’s leading international match referees, has always insisted that it was a change designed to capture a wicket late in the day rather than a case of calling off the dogs. At no point did he consider that a necessity, believing that to be the responsibility of others.

‘If the umpires didn’t think it was intimidation, it was not up to me to intervene,’ he says with quiet conviction. ‘You had to leave it to the umpires. They were experienced men who had played the game. Close and Edrich were just past it and couldn’t get out of the way of the ball. They were just paralysed. What could I tell the bowlers? Don’t pitch it there because there is a crack there? We had faster guys than England and the problems were caused by the cracks on the pitch.’

Besides, Lloyd had seen his team suffer against Lillee and Thomson a few months earlier and had taken their punishment without any resort to squealing. ‘Australia broke a lot of fingers. I remember taking my guard in blood in Perth because Kallicharran was hit in the face. Holder and Julien got hit as well. We took it as part and parcel of Test cricket. We didn’t complain that they were bowling short balls at us.’

Frank Hayes, despite potentially being on the receiving end, supports the opposition captain. ‘You leave it to the umpires. If you are battered and bruised you have to accept it. Clive captained the side and the laws of the game allowed him to do what he did. You can’t say it is unfair.’

With the ball in the friendlier custody of Padmore, it was time for some light comedy. Recalling the spinner’s first delivery, Selvey says, ‘Edrich turned one round the corner, stood back and leant on his bat, only to look up and find that Closey was down at his end! Closey wore plimsolls to bat in and Edrich didn’t hear him coming. He nearly got run out getting to the other end.’

Edrich, that most unselfish of batting partners, would now take his turn at facing Holding. The ball was kept up to the bat and, at last, the storm seemed to have passed. Daniel came back and the score advanced by eight runs, four no-balls and a driven boundary by Edrich, before Close dealt easily with the last over of the day from Padmore. A score of 21 for 0, but runs had been unimportant. No one would remember the run-rate; the brutal images of the session continue to live on after three decades.

When Close and Edrich returned to the pavilion, teammates simply gawped at them as they might war colleagues showing up back at base after being presumed dead. It was Edrich who broke the silence by looking out across the ground at the scoreboard and breaking into manic giggling that grew into a roar of laughter. ‘Do you know what your score is, Closey? One! We’ve been out there for 80 minutes and gone through all that for one! Closey, was it worth it?’

Steele recalls, ‘We hadn’t lost a wicket, which was an incredible thing, and Closey is stood there, no teeth, no hair and a big grin. He loved it. He bloody loved it. Some of them had been shitting themselves in the toilet because they didn’t want to go in. ‘What d’you think?’ he said. I said, ‘Brilliant.’ When he took his shirt off he was bleeding, he had the seam marks all over him.’

Close was chuckling painfully as he revealed the lumps and welts across his chest. According to Pocock, it appeared ‘as if somebody had forced handfuls of marbles beneath his skin – and he had red criss-crosses on his chest from the seam of the ball’. But Close reassured his colleagues, ‘You want to see the state of the ball. There’s no shine left on it. It’s all on me!’

Selvey adds, ‘It was horrible. He’d had his ribs broken, no question.’ But when physiotherapist Bill Ridding suggested that Close should go to hospital for an X-ray, his reply was. ‘I’ll be all right, lad. Just give me a Scotch.’ Gulping down the reviving liquid, he shuffled off to the shower. ‘Watching that guy play out there this evening,’ said Edrich to his colleague’s departing back, ‘made me proud to be an Englishman.’

Despite their battering Close and Edrich returned on the Monday morning and took their partnership past 50 before Edrich was dismissed, after which England capitulated for 126 and a defeat by the enormous margin of 425 runs. England lost the next two Tests as well but Close was not involved as he and Edrich had both played their last Test. The decision to drop them might well have been a sensible one but, as with Close’s previous seven such experiences, the insensitive manner of it was what rankled.

At the end of the 1977 season Close finally retired although he continued to play for his own XI against the tourists at the annual Scarborough festival. He was in his 56th year when he made his last First Class appearance against the New Zealanders in 1986. With the end of his Somerset career the old poacher turned gamekeeper and served as an England selector between 1979 and 1981, and he joined the Yorkshire committee in 1984. As a coach he captained the Yorkshire Colts well past retirement age and was happy to bat in the nets against young tyros like Ryan Sidebottom and Chris Silverwood with minimal protection and when, as he usually did, he fielded at short leg there was not a helmet in sight.

In the autumn of his life Close lived in Baildon near Bradford and it was at home that he died on Sunday at the age of 84.

“Grovel” received great critical acclaim on publication in 2007. You can read CW’s review here.

What an absolutely brilliant read.

Thanks for posting that – enjoyed it hugely.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am GMT 25 February 2010

Bloody superb. Great stuff.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 25 February 2010

So good.

Comment by pasag | 12:00am GMT 26 February 2010

Alternately had me sweating, recalling that hot summer, and chilled at the description of the cricket. A brilliant, brilliant feature (all three parts), best I’ve read on CW.

Comment by Dave Wilson | 12:00am GMT 27 February 2010

Wow! It’s only now at 59 that I’m truly discovering the feats of some of my relatives, thanks to writers like that, and belatedely settling down to Cricketing Days, end of an innings etc: makes me proud to be English and have Edrich blood in me. Will re-read Alan Hill’s take of this match when I get home tonight, too.

Comment by Jasper Edrich | 12:00am GMT 1 March 2010