Mike Brearley, C.L.R. James & Socrates

Gareth Bland |

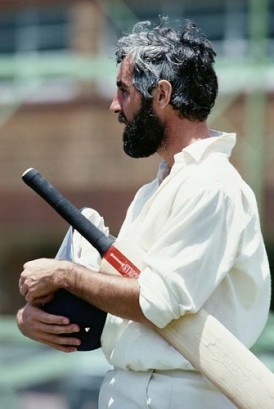

He was always thought of as high-minded, and even Rodney Hogg famously asserted that he “had a degree in people”, but Mike Brearley’s career outside cricket is perhaps singularly unique in the modern age. It was in 2013 that he delivered a lecture at The University of Glasgow that embraced each facet of his professional existence. Applying the Socratic method of questioning to his chosen subject, Brearley delivered an address to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the publication of C.L.R. James’ seminal Beyond a Boundary.

Having retired from all cricket at the end of the 1982 English season, Brearley opted to move full-time to the life of the mind and the profession of psychoanalysis. As an undergraduate Brearley had read Classics and Moral Sciences at St Johns’s College, Cambridge, and subsequently embarked upon a lectureship in Philosophy at Newcastle University, a task which he combined with playing cricket for Middlesex. As his professional cricket career neared its end, though, Brearley began to train in psychoanalysis in preparation for his life beyond the game.

The context of C.L.R James’s work – that of a Trinidadian-born intellectual and historian tracing his love of the game while simultaneously being the subject of colonial rule – was, and is, doubly significant given Brearley’s observations of class differences in the English domestic game. James’ work was published in the same year, 1963, in which the last Gentleman v. Players game was played. Coming a year before Brearley received his county cap from Middlesex, the English game’s domestic version of cricketing apartheid was becoming a tired anachronism. In 1961, at the Scarborough Festival where a Gentleman v. Players fixture was in full swing, a young Brearley, just 18, had turned up at the dining table sans the obligatory dinner jacket. Later, ahead of the final game of its kind Brearley had dismissed the notion of the fixture as being one for “old colonels”.

Brearley’s subject, C.L.R. James, was all too aware of the contradictions inherent in his fixation with a game which was a colonial implant. Such conflicts were evident even in his choice of team. As the academic Paul C. Hebert wrote in his review of Beyond a Boundary:

For James, choosing a team to play for required navigating a complex system of overlapping social structures in which people sought to maintain whatever advantage their skin colour or class position gave them. White teams like Queen’s Park and Shamrock would not accept James because of his race, playing for Stingo, the team of “the plebeians, the butcher, the tailor, the candlestick maker, the casual labourer, with a sprinkling of the unemployed” was not an option because it represented a step down for a middle-class man like James. Of the remaining possibilities–Maple, a team made up of “the brown-skinned middle class,” where members tried to safeguard the social advantages of a lighter complexion, and Shannon, “the team of the black lower-middle class”–James chose Maple, a decision, that “delayed [his] political development for years” by further isolating him from the popular masses.

Although James had authored the pamphlet The Case for West-Indian Self Government in 1936, he had also devoured, with relish, the Western literary and philosophical canon from a young age. Speaking to an African-American scholar he said of himself “I am a Black European, that is my training and outlook”.

For the cricketer turned philosopher turned psychoanalyst Brearley, his own contradictions were apparent and were also evident to the man himself. Asked about the antipathy which Australians crowds had displayed towards him during the 1979/80 England tour, Brearley professed that “in the externals” such as accent and university background he represented “the kind of Englishman that they (the Australians crowds) were very suspicious of”. However, as Ian Botham’s biographer Simon Wilde had noted, Brearley was a much more layered personality when it came to his English teammates. Wilde wrote:

“He (Brearley) was well grounded and pragmatic – he was a doer as well as a thinker. His antecedents were far from grand and – perhaps helpfully as far as Botham was concerned – from the North. His grandfather, who came from Heckmondwike in Yorkshire, had been an engine-fitter as well as a lively fast bowler; his father Horace, while maintaining the family passion for cricket as a batsman, became a teacher in Sheffield and then in London. Brearley himself seemed happiest surrounded by hard-headed Northern cricketers such as Hendrick, Miller, Randall, Willey, Boycott, Taylor, and (if family origins count) Botham, while one of the few players with whom he failed to hit it off was Phil Edmonds, born in Zambia and every bit the bolshie colonial.”

This very same independence of mind and originally of thought was evident to the journalist Paul Edwards, who, in a The Cricket Monthly interview, observed of Brearley “He is suspicious of the British establishment yet also dislikes north-west London and Guardian-reading conformity. Kerry Packer was never his style, yet he understood the motivations of the cricketers who joined World Series Cricket and he was insistent they be picked on merit for the England team he captained in 1977“.

The ability to comprehend contradictory poses and concepts is perhaps inherent in Brearley’s training and mindset. It is also central to the Socratic method with which Brearley had applied to his subject C.L.R. James. Essentially, a technique which fosters self-discovery, since it involves in-depth questioning and discussion, the Socratic method in turn can reveal a greater depth of self-awareness and understanding, and even tease out and appreciate a subject’s own inherent contradictions. Just as Brearley was able to observe the injustices of apartheid when touring South Africa in 1964/5 and be vocal about the treatment meted out to Basil D’Oliveira by the England selectors in 1968/69, and take moral stances on both, so Brearley was able to insist that his own Packer-bound England teammates should be picked on merit.

The popular image of Brearley is of English cricket’s grey eminence, certainly when considering his intellectual prowess and career post-cricket, alongside his literary output and demeanour as captain. As Jonathan Calder remarked in his Liberal England blog, “When Brearley became England’s captain in 1977 it was almost as though Jonathan Miller or Michael Frayn had been put in charge. Brearley was a representative of liberal North London in an age when cricket was still run by the establishment.” How ironic, then, that Mike Brearley’s finest cricketing hour should be synonymous with a man, in Ian Botham, whose political outlook is the very antitheses of North London’s cultural establishment.

Superbly written article.

Comment by Roy Gibbs | 1:55pm BST 2 June 2024

Splitting hairs a bit, but 1962 was the year of the last Gentlemen v Players match; 1963 was the year in which the amateur/professional distinction was abolished.

Comment by Andrew Bull | 7:12pm BST 7 June 2024