How Times Have Changed

Martin Chandler |

Cricket is a sport in which tales of past glories are often part and parcel of the present. The story of the Headingley Test between England and Australia in 1981 is one of the best known. England were looking to retain the Ashes although, thanks to the split in the game that occurred in 1977, by then healed, between the cricket authorities on the one hand, and Kerry Packer and his World Series Cricket on the other, cricket’s greatest contest was in a state of some confusion. In the 1977 contest, which followed the shock of meeting Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in 1974/75, England had regrouped under Mike Brearley and comfortably overcome an Australian side that lacked Ian Chappell, Ross Edwards and Lillee. In addition many of the party who did tour were no doubt, to some extent at least, distracted by the cloak and dagger attempts, largely successful, to recruit them for Packer’s “circus”.

When the time came for Brearley to defend the Ashes, in 1978/79, his side proceeded to decisively beat what was, at best, an Australian second eleven and, as a result the famous old urn was retained for the next full series, that scheduled for 1981. Unfortuately by the time 1981 arrived that was fairly meaningless as a three Test series in 1979/80, hurriedly arranged to celebrate peace returning to the administration of the game, had seen a proper Australian side brush Brearley’s England aside with ease. It had been agreed beforehand that three Tests did not constitute an Ashes series, thus England’s hold on to the Ashes was purely technical.

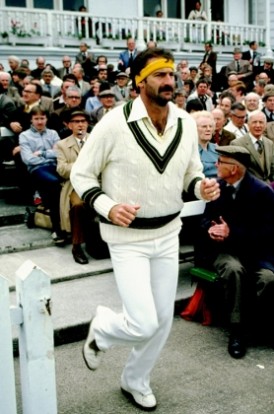

By 1981 Brearley was no longer England captain having handed the baton on to the talismanic Ian Botham. He passed on what seemed to be a poisoned chalice and so it proved. Back to back defeats against Clive Lloyd’s West Indies temporarily tarnished Botham’s aura and, after Australia won the first Test in 1981, followed by his recording a pair in a lacklustre draw in the second, the selectors reacted in the way that selectors do and demoted him to the rank and file and brought Brearley, as captain, back for Headingley. Initially it seemed to have been a pointless move. Aussie skipper Kim Hughes won the toss and the visitors batted. England followed on 227 behind and at one point on the fourth afternoon were 135-7, still 92 short of making Australia bat again. There were of course two momentous acts to come; Act one, enter stage left Ian Botham with the bat. Act two, enter stage right Bob Willis with the ball. The story of how England went on wrest victory from the jaws of defeat is one of the best known in the game.

There was a big story off the field as well. On the Saturday afternoon bookmakers Ladbrokes, who had a tent at the ground, decided to offer odds of 500-1 on an England victory. At the time those odds were first posted bad light had caused England’s second innings to be suspended at 0-1. Ladbrokes got some free publicity from the electronic scoreboard operator once he learned of the odds and decided to put them up on the board. In the gloom it was the only thing the crowd could see and the price on offer, and accordingly Ladrokes, were the subject of much comment in both the BBC television and Test Match Special commentary positions. Ladrokes disclosed later that they took GBP25,000 on the match and paid out GBP40,000. Given what was to occur, and that their name figured constantly in the reports of that, their “advertising outlay” of GBP15,000 proved to be a most worthwhile investment.

The odds offered were also the subject of much interest in the Australian dressing room and a couple of days after the Test ended The Sun, that great bastion of the English gutter press, promoted cricket to its front page. The scoop appeared under the headline “Mystery of Ashes Bets Coup” and went on “Two Australian cricketers allegedly netted GBP7,500 between them yesterday by backing England to win the Headingley Test”.

The embarassed Australian party then individually engaged their mouths before collectively engaging their brains. Manager Fred Bennett, while making the point that there was no law against betting in cricket, assured journalists that he had spoken to his entire team and that all had emphatically denied making a bet. Unfortunately for Bennett his skipper, Kim Hughes, was quoted on the same page as acknowledging that two of the team had gambled, but only because the odds were so attractive. Lillee was quoted as saying “I don’t bet on cricket. Is somebody having a go just because we lost?”

The following August Lillee produced his second volume of autobiography, My Life in Cricket, in which, to the irriation of Rod Marsh, he admitted what had happened. He explained that he considered the odds so ridiculous in a two horse race that he initially considered betting GBP50 on the outcome, and not the ten that he eventually placed. Marsh, according to Lillee, was sceptical as to whether there was any value at all in the bet but, at the eleventh hour, decided he would throw a fiver at it. Lillee confirmed that the actual placing of the bets was done by the team’s English driver, Peter “Geezer” Tribe.

As we are looking at events that unfolded almost thirty years ago it is worth pausing to consider the amounts involved in real terms. Lillee’s actual winnings for his ten pound stake, GBP5,000, would certainly have enabled him to buy, for example, a brand new Ford Capri and ship it back to Australia. Had be backed his initial judgment and placed the fifty pound bet he would have received a life changing sum. As to what actually became of the money a lot of drinks were bought, and a set of golf clubs was bought for “Geezer” who, together with his wife, was later treated to a holiday in Perth as well. A tidy sum would also have gone to the UK Exchequer. In those days tax had to be paid on bets – punters had the option of paying tax on the stake. If that option was not taken, as I believe to be the case here, then the whole of the winnings were subject to tax.

At the time his book was published Lillee was coming to the end of his great career, but still had a few Tests to play, so his making matters public at that stage certainly appears to be consistent with his own steadfastly maintained position that he believed he had done nothing wrong. He had provided a few headaches for the Australian Board over the years and this was another one. When the archives of Cricket Australia were opened up to David Frith and Gideon Haigh for the purposes of their 2007 collaboration, Inside Story they indicated there had been “considerable discussion” about Lillee’s revelations, although the upshot of that was simply that future contracts would have a prohibition on players betting on matches or series in which they were involved. There was a letter written to Lillee, expressing concern about the publicity surrounding the affair, but at the same time accepting that the bet had had no impact on his performance. In reality it was barely an admonishment, let alone any sort of disciplinary action.

At the same time as Lillee’s book was published Marsh went into print as well with The Gloves of Irony. Marsh received legal advice to the effect that a chapter in his book dealing with the bets should be withdrawn and it duly was. Lillee’s book created something of a storm and sold many more copies than Marsh’s, although Ian Brayshaw, who had ghosted books for both Lillee and Marsh in the early 1970’s, expressed the view that the Lillee revelations were ill advised. Whether Lillee was just taking another gamble, or he had strong grounds for a belief that the Board would take no action I do not know, but certainly Marsh’s 2004 biographer, Mark Browning, speculated that he made more money from the book than he had from the original bet.

The problem with sportsmen betting against their own side is that it gives them a conflict of interest. The obvious imputation that might have been cast was that, with a large sum of money coming his way if his team lost, that Lillee, or Marsh for that matter, might underperform. On that point the most significant factor was, in this writer’s opinion, the report in The Sun. If the newspaper had believed that Lillee and/or Marsh, or indeed anyone else given that their information was that the whole team had discussed the bets, had deliberately played at less than their best then they surely would have said so. As the bets were actually laid it seems highly unlikely that the pair could have been libelled, yet despite that opportunity the overall thrust of the article was much more in the nature of mischief making for the sake of it rather than any suggestion of dishonesty. It is self-evident that the odds on offer were ridiculous and England’s wicketkeeper at Headingley, Bob Taylor, has quite openly said he tried to get to the Ladbrokes tent in order to make a bet. Sadly for Taylor, who intended to wager just two pounds, autograph hunters prevented him getting there and winning his thousand. In the commentary box former Ashes captains Ted Dexter and Richie Benaud were also foiled by circumstances beyond their control in their attempts to take advantage of the odds on offer.

So were Lillee and Marsh giving it their all after they laid their bets? Having watched the match on television, both at the time and on many occasions since, it is blindingly obvious that they did just that and I do not ever recall anyone whose opinion was to be respected making a serious suggestion to the contrary. To illustrate the point most vividly no England supporter who saw it will ever forget the highs and lows of the final overs. Before lunch on that fifth morning, with Australia 56-1, everything seemed lost. Immediately Willis changed ends however it looked a different game. As soon as he removed Trevor Chappell the atmosphere changed completely and when, not all that long after lunch, Geoff Lawson went to make it 75-8, it seemed that the victory would be a comfortable one and we all relaxed. It was then that Lillee and Bright added 35. After the panic that had clearly spread through the Australians Lillee took charge and looked in control. He was unfortunate to miscue an intended nudge into the onside and in doing so pick out the only fielder in front of square, Mike Gatting at mid on, who dived forward to take a far from straightforward catch.

Having given what appeared to be a full account of the incident in My Life in Cricket Lillee chose to revisit it again in his 2003 autobiography, Menace. The chapter dealing with the episode begins, surprisingly in view of the foregoing “….. there were suspicions we might have thrown the game to win a 500-1 bet”. In the two decades that had passed since that day in 1981 the cricket world had lost much of its innocence. Match fixing at all levels of the game, including Test cricket, had been uncovered and the reputations of famous players like Hansie Cronje, Salim Malik and Mohammad Azharuddin had been damaged beyond repair. Others, including Shane Warne and Mark Waugh, had been sucked in to the wide ranging enquiries that followed.

It seems likely that Lillee’s comment was prompted more by his own reexamination of the events of 1981 in the light of these scandals rather than any credible allegations being made against him, and he did acknowledge, with the benefit of hindsight, the error of his ways. He must have shuddered to think what might have been the outcome if, for example, he had received an unplayable delivery from Willis first up and been dismissed for nought. Even worse was the fact that he deliberately lifted two deliveries over the slips in the course of his innings. They were well judged shots but, had his judgement just been a fraction awry, it would have looked like he was giving the slips catching practice. Given that it was the manner of his batting more than anything else that allayed any concerns then history might have judged him rather differently.

Lillee’s memory is, however, unreliable in Menace. Firstly he says that his initial instinct was to stake one hundred pounds and not fifty. Later he makes the point that had he known the result in advance he would surely have “put my house on it”. It was a silly point to make and one totally devoid of merit. In any team game you need more than one or two players onside in order to fix a result and to stake everything on a situation such as this would have needed the sure and certain knowledge that the majority, if not all his teammates would have done what was necessary. Lillee’s much better point was the openness with which the bets were discussed in the dressing room coupled with the fact that no real effort was made to prevent the media finding out about them.

Lillee goes on to stress the nature of the contest and that what happened really was an extraordinary fluke. First of all he described Botham’s innings as “bloody lucky” and therefore no fault of the Australian bowlers. This is certainly correct. Botham threw the proverbial kitchen sink at the ball. There were plenty of edges and much playing and missing went on. Where Lillee is wrong is his assertion that “We dropped him countless times….” . It is another poor point, for two reasons. Firstly if it were true then that surely would give rise to well founded suspicion – in 1981 international cricketers were expected to safely hold the overwhelming majority of catches that came their way. Secondly it simply wasn’t true. Early on in his innings Botham slashed one through the gully area that Bright put down – it should however be borne in mind when judging Bright that Botham was striking the ball with such power that at one point an attempted hook, that he timed so badly that it struck his bat somewhere near the splice, still bounced only once before crossing the mid on boundary. The only other possible chance was when Botham was on 109, when Marsh got his fingertips to a top edge. As matters turned out it wasn’t a chance at all although, when the incident was replayed, it looked like Marsh might have increased the possibility of making the catch had he gone for it with one hand rather than both. In any event neither the bowling, fielding or wicketkeeping could be criticised.

Nor, according to Lillee, could the Australian batting be blamed. He was as complimentary about Willis’s inspired bowling spell as he was critical of Botham’s innings. He was correct again. As already mentioned something intangible did change immediately the, by then, demonic Willis started bowling from the Kirkstall Lane End.

Menace goes on to refer to an earlier game, again in Yorkshire, that My Life in Cricket did not mention. Lillee explains that the 1972 Australian team had collectively put a bet on their taking five wickets in the first session against the county side. He goes on to say that with the fall of the fifth wicket (he wasn’t playing in the match) he went to collect the winnings only to have it explained to him that there could be no payout before lunch, as if a sixth wicket fell the bet was lost. Lillee then mentioned this to Bob Massie, who was fielding in the deep and who then, in the five minutes before the interval, clung onto a steepling catch from a mishook from Chris Old. Why mention it all though is a question that struck me when I first read Menace. Although no reason is proffered in Menace it must be assumed that the reason is the incident being referred to in a book written by Ken Piesse, Cricket’s Greatest Scandals, that was published in 2001. Piesse quoted the words of Rod Marsh about the incident “… Dennis yelled out that we couldn’t take any more and we all acknowledged the fact and proceeded cautiously” He added, no doubt tongue in cheek, when referring to Massie’s catch, “We all raced down to kick his backside!” As to the question of whose recollection is correct I can only speculate but Lillee does clearly describe the match as having been played at Headingley when it actually took place, as correctly identified by Piesse, in Bradford.

When organised cricket began betting on the game was widespread and conducted quite openly and legally. It seems highly likely that the keeping of scorecards and the preparation of batting and bowling averages originated, at least in part, to enable form to be assessed by the gambling fraternity, both bookmaker and punter. As has been relearnt in recent years where there is gambling there is a huge temptation for fraud, particularly amongst lowly, or relatively lowly paid professional cricketers, and by the 1870’s bookmakers had been banished from cricket matches. It was only a few years before 1981 that they returned to English cricket grounds and even then the cricket betting was just a bit of fun and generated only a small fraction of the revenue generated. The main interest of the proprietors of the betting tents was to take bets for horse racing. In Australia at this time there were no bookmakers at grounds at all. In the circumstances a little naivety was both understandable and forgiveable.

There can be no doubt either that Lillee expressed some odd views in Menace, first and foremost being his conviction that those who sold information to bookmakers should not be treated in the same way as those who accepted money in return for taking action that would alter the course of a game. Journalist Bob Harris ghosted the book for Lillee and it must be likely that, in common with many “authors” of sporting autobiographies, Lillee did not give the content of the book the attention it merited. That said Harris surely did him a disservice by not thinking that part of his narrative through. It does not need me to highlight the absurdity of viewing the giving of information about tactics and team selection, on the one hand in conversation to a fan outside the ground, and on the other to a bookmaker in return for money, as being a distinction without a difference. Alternatively if we do take that assertion at face value as being the honest belief of a 54 year old former international cricketer then surely we should not be judging an 18 year old from rural Pakistan too harshly?

When cricket betting became a problem in Victorian times the solution found was the simple one of closing it down. In the internet age that is not possible and indeed many observers have suggested that, in actual fact, were betting to be embraced legally throughout the sub continent that that in itself might improve matters. Until a solution is found however it is still necessary to find a means of dealing with the players who become involved in the seamier side of the sport.

How seriously should offenders be treated? There is a category of cricketer, the match fixer, Hansie Cronje, Mohammad Azharuddin and Salim Malik being the most obvious examples, for whom a life ban must be mandatory. Quite apart from the criminal nature of the deceptions involved the integrity of the game itself is seriously undermined. But that should not have been the end of their stories (and of course the bans of Malik and Azhar were lifted within a few years anyway) and all three should have faced criminal prosecutions. Only by the criminal process can these men face being deprived of their liberty, and having to deal with the wide ranging and far reaching powers of the criminal courts to deprive them of their ill gotten gains.

Then there are those who provide bookmakers with information for reward, as Lillee seemed to consider was aceptable. This is what Shane Warne and Mark Waugh admitted to and for which each was fined, it would appear, about double the amount that he received in the first place. Whatever Lillee might say this is a serious offence and may amount to a crime. If a young player is collared at a cocktail party the night before a game and inadvertently passes information that may well be different, but the fact of money changing hands makes this little better than match fixing even if, as Lillee would doubtless point out, it serves only to confirm rather than alter the course of a match.

What of those who agree to accept money to underperform but then for whatever reason don’t do what they were paid to do? Herschelle Gibbs accepted money from Hansie Cronje to score less than 20 in an ODI. In fact he scored a rapid 74, clearly changing his mind. In that same match Henry Williams, a seam bowler, accepted money to concede more than 50 runs in his ten overs. Injured after sending down just 11 deliveries he too did not deliver, albeit for very different reasons. Six month bans were all Gibbs and Williams received. Clean records and assistance in testifying against Cronje notwithstanding surely those punishments, and the lack of a criminal sanction, were unduly lenient?

Changing sports to football Peter Swan was an England international defender who played for Sheffield Wednesday in the early 1960’s. Swan, together with teammates David Layne and Tony Kay, were persuaded to agree to ensure that their side lost a match at Ipswich Town. Swan’s reward was the return on the fifty pounds his wife put on Ipswich to win at two to one. All involved agreed that the Ipswich side won the match comfortably and the guilty trio needed to do nothing. Their criminality was, of course, what they were willing to do and had agreed to do but on that isolated occasion was their conduct more or less serious than that of Malik, Azhar or Cronje? For the Sheffield Wednesday three there was a criminal trial, and a four month prison sentence at the end of it. On release the FA banned them for life – seven years on the bans were lifted but too late for three good footballers to make a mark on the game they had graced, and then disgraced.

Former Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar, together with fellow players John Fashanu and Hans Segers, together with a Malaysian businessman, faced trial twice in 1997 in respect of allegations of match fixing levelled, largely, on the basis of Grobbelaar’s taped confessions in a newspaper “sting” type of operation such as that which has brought Mohammad Asif, Salman Butt and Mohammad Amir to the attention of the Metropolitan Police and the ICC. Despite the confession the jury still saw fit to acquit all four defendants at both their trials. In a subsequent civil case, that ultimately travelled all the way to the Supreme Court, a succession of Judges decided that, whatever the jury concluded to the criminal standard of proof (beyond reasonable doubt), that there was enough evidence of dishonesty to the civil standard (balance of probabilities) to deny the players the protection of the law of defamation.

No doubt influenced by the outcome of the Grobbelaar case the Crown Prosecution Service decided, in 2009, that it was “an inappropriate use of police resources” and “not in the public interest” for a criminal investigation to continue against former Southampton and England striker Matthew Le Tissier. In his autobiography, published that August, Le Tissier had disclosed that in 1995 he stood to win a four figure sum provided the first time the ball went out of play in Southampton’s game against Wimbledon was within a minute of kick off. Le Tissier wrote of his desperation to get the ball out of play after, in his efforts not to raise suspicions, he had failed to put the ball out of play with his first touch. Quite how those conclusions could have been reached are beyond this writer. The decision sends out all of the wrong signals. It tells players they can spot fix with alacrity and having done so can, without fear of any adverse consequences, stick their greedy noses back in the trough after retirement to make sure of an increased payday on publication of their memoirs. Not only did the CPS take no action the FA failed to do so either, and Le Tissier’s hysterical outbursts are still to be heard emanating from the SkySports studios each Premier League matchday. If, as the Crown Prosecution Service quite properly say it is, consistency in the decision making process is one of their aims, then there is a certain logic for saying that Asif, Butt and Amir should not, on the Le Tissier principle, be prosecuted whatever evidence might have emerged from the police investigation that has just concluded.

In fairness to the ICC they have done a decent job of sorting out how they deal with disciplinary matters. There is a code of conduct which applies to all involved in the game and which spells out with admirable clarity what is expected of players and there are guidelines as to the sanctions to be applied if the rules are broken. Having said that it is however self evident that however hard it tries the ICC can only go so far. It is reliant on the prosecuting agencies of its member countries if the ultimate deterrent is going to be available for the sort of misconduct that undermines public confidence in the game’s integrity. The amount of money that is at stake is such that the prospect of imprisonment and asset confiscation is required. In England in the 1960’s it was considered worthwhile to prosecute the Sheffield Wednesday three. Having done so successfully imprisonment was still the only course considered appropriate despite only a relatively small amount of money being directly involved, and the men concerned being of good character, and having had their careers ruined by their actions. Those sort of attitudes are surely essential if the game is to have any chance of being free from the match and spot fixing scandals that have bedevilled it in recent years.

In many ways it is frustrating that so little of the actual proceedings in Doha have been reported, but now that the Crown Prosecution Service have decided to lay charges against all three players let us hope that remains the case. The defence teams will undoubtedly try and exploit whatever publicity the case attracts with a view to arguing that their clients will not be able to have a fair trial. In the circumstances while I am as anxious as anyone to know more about the evidence I am happy to wait to read the reports of the progress of the trial as it unfolds. A particular concern would, in my view, arise if the detail of the evidence that Butt, Asif and Amir gave to the ICC tribunal were held up now for public scrutiny and comment. If that were to happen then certainly my feeling is that a fair trial would be difficult to achieve.

I have to confess that, initially at least, the decision to prosecute Butt, Asif and Amir came as something of a surprise to me. I had rather assumed that after the Grobbelaar/Segers/Fashanu experience, and the subsequent Le Tissier decision, the matter would be left to the ICC. It is gratifying to see that Simon Clements, Head of the CPS Special Crime Division, has felt able to say “we (the CPS) are satisfied there is sufficient evidence for a realistic prospect of conviction and it is in the public interest to prosecute”. I know Mr Clements from a past life when we played cricket together and, had I known the matter was in his hands, I would not have been so sceptical in the first place. He is a man of great integrity so the Defendants can rest assured that they will be treated fairly. At the same time he is also diligent and tenacious and will not be knocked off what he considers to be a right and proper course by any of the silly games that defence lawyers play, particularly when their clients are in difficulty. In short I am confident that, to the extent that it ever can be, justice will be done in this case.

In the ICC proceedings the decision of the ICC has just been announced and, on the basis of what little is in the public domain, it is difficult to see any coherent basis upon which their findings of guilt, or the punishments imposed, might be challenged. Would those findings alone serve to stop those who might be tempted in the future by the bookmaker’s lucre? I am sure they will make any player who is tempted think twice, but I suspect that there will be plenty who might still be prepared to take the gamble, if the price was right. What I have no doubt about is that there would be far fewer were it to be known that, if caught, the death rattle of a cell door closing, together with the prospect of coming out of prison to a future stripped of all assets, might be the result. That prospect is why it is so important that prosecuting authorities investigate these allegations fully and that where there is a case to answer that the matters are tried – if the prosecution fails so be it – but any sportsman who is tempted to sell his soul to the bookmaker must do so in the sure and certain knowledge that he risks his freedom and what wealth he has. The fear of “only” losing his livelihood together with his reputation has clearly, in the past, seems not to have been sufficient deterrent for some.

To return to where I began what of Denis Lillee and his story? As I hope is clear I have not told the “500-1” story in order to cast any stones in his direction. Rather I have referred to it to show just how much attitudes have changed in a short space of time. The Lillee story was one which produced some good entertainment at the time, and made a couple of Australians look a little foolish. Lillee himself, and Rod Marsh, each came into not inconsiderable sums of money, and while there was doubtless strong disapproval in some quarters at the chain of events no one saw the issue as one that gave rise to grave concerns.

What would Denis Lillee have done if he’d been asked to “spot fix” in a manner that would have had no influence on the outcome of a cricket match? If, for example, he had been asked to bowl a no ball first up at the start of his second spell – he alone knows the answer to that but I cannot imagine that, despite his stated views on the admittedly slightly lesser transgressions of Messrs Warne and Waugh (M), that he would have even contemplated taking money from an outsider for doing so no matter how innocent the action requested might have seemed. Had he been invited to do so by a trusted teammate, or respected opponent for that matter, for the craic and nothing else, then I am not so sure, but that comment is merely intended to reflect Lillee’s larger than life personality rather than be a criticism of him.

Turning that thought round I leave Lillee, but remain at Headingley, and set the time machine for 28 years forward to July 2010 and the second Test between Australia and Pakistan. Australia then were certainly still considered a strong side. Pakistan had started the two match series in a state of some disarray, minus their two leading batsmen. They then lost heavily at Lords before losing their captain prior to the Headingley match. What would have happened if Ladbrokes, keen to stimulate a bit of interest, had offered some silly odds on a Pakistan victory, and a couple of the Australian side couldn’t resist the temptation? Leaving to one side the internal breach of contract issue that the ACB would have to deal with I have absolutely no doubt that the incident would not have unwound in the same way as Lillee’s did in 1981 – the players concerned would inevitably have been hauled over the coals by the ICC and severely dealt with, and in addition, it would seem there would have been every prospect that they would have faced a police investigation, and the very real risk of prosecution. How times have changed.

A marvellous piece, well done Mr F

Comment by GeraintIsMyHero | 12:00am GMT 6 February 2011

FFs memory > Dennis Ls memory.

Great read.

Comment by Ausage | 12:00am GMT 6 February 2011