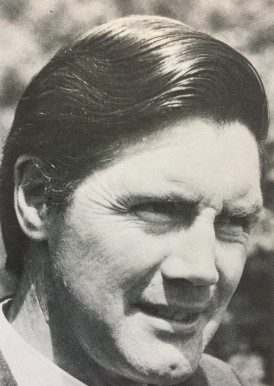

Gerald Howat

Martin Chandler |

Bad luck batsman, were the only words Gerald Howat ever spoke to me. Had I realised who he was at the time I would have had a great deal more to say to him after our game had finished. It was back in the 1980s and he would have been pushing 60, but he was still keeping wicket for Moreton Cricket Club in Oxfordshire, something he had done for many years, and it would be a few more years before he hung his gauntlets up (although he had not played regularly for some time before it, his final appearance came at the age of 77!).

At the time I was a bit more concerned about his son, Michael, whose bowling I was facing. Described on cricketarchive as medium fast double blue Michael Howat was, of course, far too quick for a club batsman of such modest ability as I and my innings against him lasted just two deliveries. The first would have bowled me if the stumps had had an extra coat of varnish, and the second pinned me as plumb in front as it is possible to get.

The problem with having been dismissed so quickly was that, naturally in the circumstances, looking at the scorebook was the last thing I needed or wanted to do, so I never picked up on the surname of ‘keeper and bowler. Had I done so then, at that stage already owning a couple of books with Howat’s name on them, I would certainly have taken the opportunity of speaking to him in the pub after the game.

Sadly for me however none of those members of my team who knew who Howat was bothered to enlighten me until our end of season tour a month or so later. I was to look in vain for the name Howat in the opposition ranks on the couple of subsequent occasions I played at Moreton. It was my bad luck that our fixtures then were scheduled for a time he was away.

Howat was born in Scotland in 1928, the son of an Episcopalian minister. I do not recall, from those three words Howat uttered within my earshot, any obvious accent although I dare say it may have been discernible. In any event Howat was educated at Trinity College in Glenalmond before reading history at Edinburgh University, by which time his passion for cricket was well established. He had, by all accounts, already shown some ability as a wicket-keeper and had the good fortune to be coached whilst at school by, amongst others, Learie Constantine.

After University it was, in the manner of the times, National Service for Howat and he opted for the Royal Air Force. His first gainful employment then took him out to the Caribbean where he worked as a teacher for an oil company, Trinidad Leaseholds. The storeman at the school where Howat taught was Sonny Ramadhin, and whilst he was employed there he renewed his acquaintance with Constantine, who was the company’s lawyer.

It was 1955 that Howat returned to the UK. A teaching career that began at Kelly College in Tavistock took him then to Culham College and then Radley College in Oxfordshire. He also did a research degree on the subject of the place of history in education and for a time was involved in publishing being, on a part time basis, the general editor of the historical division of Pergamon Press, a company that was part of the Robert Maxwell empire. For three years Howat was also a visiting professor at Western Kentucky University in the US.

As an academic writing came naturally to Howat and there were many papers and literary contributions in his field throughout his career in education. His first book however was on a different theme. Co-authored with his wife, Anne, who he had met at University and had become a consultant psychiatrist, the book was The Story of Health and was published in 1967. Other books on historical and education topics also appeared.

In 1985, still only 57, Howat would retire from education in order to concentrate on cricket and writing about the game. He had written his first cricket book some ten years previously, a biography of Constantine that won the Cricket Society Book of the Year award for 1975. Clearly Howat was in a good position to write on Constantine and was encouraged to do so by John Arlott. What is less clear is why Arlott suggested the project as it is clear that the pair had never met before the suggestion was made, so perhaps it was just the case that Arlott, believing correctly that a biography of Constantine was long overdue, did some research into likely candidates and discovered the links with Howat.

Constantine had died in 1971, and had not left behind any great cache of personal papers or correspondence. That said he had written a number of books and had featured widely in the news throughout his life. Howat had access to his daughter and brother as well as many who had known him. He spent a good deal of time in Nelson where Constantine had first made his name as a professional in the Lancashire League, and most valuable of all came across a substantial volume of material at the BBC, who had retained many recordings of Constantine broadcasts.

Subsequent to Howat’s there have been two more biographies of Constantine, and Harry Pearson’s Connie is a fine book, but for anyone interested in Constantine’s many and varied achievements after he left the game of cricket Howat’s book remains the most comprehensive account of a remarkable life.

One interesting aside on the book is the reaction to it of CLR James. The man who wrote the acclaimed Beyond a Boundary and who, in 1933, had “written” Constantine’s autobiography felt that Howat had misrepresented the relationship between the two men. Despite that criticism he still felt able to describe the book as not merely a good but a valuable book, and was later to invite Howat to write his biography. That one was an invitation that Howat decided not to accept.

There were two books from Howat in 1980 the first of which combined his passion for cricket with his skills as a historian. Village Cricket was, as the title suggests, a history of how cricket was played in English villages from the game’s earliest incarnations up to date. There was, naturally in light of Howat’s origins, a chapter on Scottish villages as well.

The Constantine biography was published by George Allen and Unwin and Village Cricket by David and Charles. The second book of 1980 was a much more homespun affair, effectively self-published by the North Moreton Press. Cricketer Militant is an unpretentious paperback biography of Jack Parsons.

Far from a household name now or then Parsons remains an interesting character. He played as a professional for Warwickshire between 1910 and 1914 before joining the Army where he earned a Military Cross for gallantry. He remained in the Army until 1923, playing as an amateur as Captain JH Parsons. He then joined the professional ranks for another six years until, having been ordained in 1929, he reverted to his amateur status as Canon JH Parsons until, at 44 he retired from the game.

A good batsman who might well have played for England in different circumstances Parsons’ life was an eventful one and, although he was in his late eighties when Howat started work, was still around to assist his biographer. The book is well worth seeking out.

Four years later Howat returned to a major publisher, once more George Allen and Unwin, for a biography of Walter Hammond. In the years after the Second World War Hammond had lent his name to a number of books and in a cricketing sense had left an indelible imprint on English cricket and in 1962 Ronald Mason had written his biography. Fine book that Mason’s was it had dealt almost exclusively with on field matters so a second look at Hammond’s life was fully justified.

Howat did a good job with Hammond, interviewing or corresponding with many of his subject’s contemporaries both cricketing and from outside the game, and from the UK and overseas. He also took the time to travel to South Africa, to where Hammond had emigrated in 1951, and interviewed his widow and daughter. The book was well received and, unlike Mason’s effort, made a serious attempt at unravelling the complexities of the man, a job that was finished just over a decade later in David Foot’s definitive Hammond biography, Wally Hammond – The Reasons Why.

The first post retirement project for Howat was one, that for me at least, remains his best book. Despite substantial volume of writing from the man himself ‘Plum’ Warner had not previously been the subject of a full biography and Plum Warner certainly filled a gap in the literature of the game. The fact that no one else has attempted the task since is telling. As with his Hammond book Howat spoke to many who had known Warner and, most importantly, the family gave Howat access to Warner’s personal correspondence and it was that that interests historians the most, vividly illustrating as it does the depth of the despair that Warner felt during the ‘Bodyline’ series and the extent of his personal animus for Douglas Jardine that developed as the tour progressed.

The Warner biography was reviewed by two of the bigger names in cricket writing, by EW ‘Jim’ Swanton in The Cricketer and by David Frith in Wisden Cricket Monthly. Swanton described Howat’s writing as competent and professional but did not give the impression of being particularly enamoured of the book. Frith was much more enthusiastic, describing Howat as a skilful biographer and his book as absorbing. As would be expected from the man who would in time write the definitive book on the ‘Bodyline’ series Frith was, unsurprisingly, particularly enthused by the contemporary correspondence.

The next, and as it turned out last, biography from Howat was Len Hutton – The Biography, which appeared at the same time as its subject celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his record breaking Ashes 364 in 1938. Four years earlier, with the assistance of Alex Bannister, Hutton had written one of the better cricketing autobiographies but he was keen to have a biography written and fully co-operated with Howat. The book is not a hagiography although as one reviewer rather diplomatically put it it is a sympathetic portrait. That said whilst Hutton might have played the game with typical Yorkshire grit and a burning desire to win, he was always a charming man.

In retirement Howat took on a number of writing tasks, many on the subject of schools cricket. He reported on that for the Daily Telegraph and, for a number of years contributed the schools section to Wisden. He also wrote regularly for The Cricketer and, if not quite with the same frequency, for Wisden Cricket Monthly and the Journal of the Cricket Society. His penultimate publication, Cricket Medley, appeared in 1993 and was an anthology of his best work, primarily from those sources, but from one or two others as well.

His oeuvre clearly marks Howat out as an aficionado of the inter war years and his 1989 book, Cricket’s Second Golden Age, demonstrates his passion for that era. It is unlikely that too many reading this will not know a good deal about that period and there are no ground breaking revelations in a book that, by looking at cricket the world over for a twenty year period does perhaps spread itself a little too thinly. On the other hand for those new to cricket history it is an excellent introduction to a fascinating era.

And that, so it seemed, was that. Howat was not a man with a fondness for modern technology and that seemingly contributed to his decision to stop writing books. That said Howat was not lost to us and he did pop up in 2001, on the face of it well outside what might have been expected to be his comfort zone. In conjunction with the MCC, bookseller John McKenzie published Vernon Royle’s diary of the 1878/79 tour to Australia, and in the same volume include the reports and scorecards of the tour that had appeared in Wisden 1880. Howat contributed an excellent and detailed introduction which, if truth be told, is a good deal more readable than the rest of the book.

Finally, and perhaps unexpectedly, in 2006 Howat produced an autobiography, Cricket All My Life. In truth the book is more of an anthology of other writings and those form the bulk of the content. But that series of chapters is bookended at the front by the story of Howat’s life up to his retirement, and at the back by an account of his later years. Sadly he did not live for too long after the book’s release and, at the age of 79, died the following year.

Leave a comment