England’s Forgotten Captain

Martin Chandler |

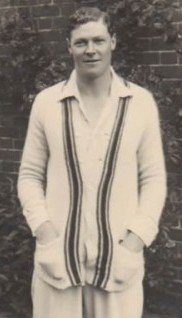

Percy Chapman had it all. He was a supremely talented all-round sportsman and came from, if not a wealthy background, one which had sufficient resources to permit a private education. By no stretch of the imagination a gifted scholar he still, by dint of his sporting abilities, got into Cambridge University where his cricket in particular prospered.

A stylish and attacking left handed batsman, and a brilliant fielder in an era when little attention was paid to that aspect of the game, Chapman had the sort of personality that made him popular with all he met. Such were the gifts that the cricketing gods endowed him with that by the age of 24 he was selected to play for England against South Africa, despite the fact that he was then playing Minor County cricket, and had yet to play in the County Championship.

Two years later Chapman was appointed England captain against Australia despite having no significant experience of captaincy. He led the side to an historic victory, and then on to further victories in each of his next eight Tests in charge, five against Australia and three against West Indies.

To add to his advantages Chapman, in the language of the times, “married well”, his bride being the sister of New Zealand’s first Test captain, Tom Lowry. The combined financial resources of bride and groom were such that there were no pressing financial problems, and the couple’s life was, for several years, one long round of parties and other social engagements.

Unfortunately however Chapman seems never to have stopped to consider living for anything other than the present. As a result as the 1930s wore on the cricketing abilities fell away sooner than they should have. Good living and the inevitable march of time took its toll on the wonderful eye, physique and lightning-fast reactions that, rather more than a sound technique, were the bedrock of his success. A career outside the game as a representative for a brewery made sure that he was never far from the social drinking that eventually consumed him. In time it was to cost him his marriage, and was responsible for a sad decline that ended in his death shortly after his 61st birthday.

Chapman was born in Reading in 1900. His father was a headmaster and an able sportsman himself and, like so many fathers, looked to his son to exceed his own sporting achievements. That encouragement took Chapman to Uppingham School. In 1917, amongst a relatively poor side, he averaged more than 111 and came to the notice of Wisden, where he was described as a punishing left handed player who scored freely all round the wicket. He was less successful the following year, but still did enough to be named as one of the Almanack’s five cricketers of the year in its 1919 edition, all schoolboys given that there had been no First Class cricket in 1918.

In 1920 Chapman went up to Cambridge. The Universities have been the whipping boys of the First Class game for so long it is often forgotten that in years gone by they produced some powerful elevens. The 1920 Cambridge side contained five future Test players, and another two who would surely have been selected had their careers outside of cricket allowed them to devote themselves fully to the game. Out of twelve First Class matches that summer the light blues won eight, and only the full might of Yorkshire defeated them, and even they were given a fright.

The abundance of top quality cricketers at Fenners meant that Chapman was originally only twelfth man for the season’s first fixture of the season, against Essex. A late withdrawal got him in the side though, and he started his First Class career with a century, the first of three that summer. Such was his impact that he became one of the few undergraduates to have represented the Gentlemen against the Players at Lord’s, in those days the biggest fixture of the summer. In a straightforward victory for an immensely powerful Players side the 19 year old Chapman scored 16 and 27*. His batting attracted praise from Wisden, and his fielding was described as magnificent.

In 1921 Warwick Armstrong’s Australians went on the rampage around England, and there were calls, sadly not heeded, to play Chapman in the Tests. He did however play in the famous match at Eastbourne when the 49 year old Archie MacLaren led an all amateur side to victory over Armstrong’s men. Two years later he went with MacLaren on a tour of New Zealand and Australia. An Australian newspaperman wrote Chapman is just a great big boy, a delightful English boy with a pleasant face and a perpetual smile. His enthusiasm and his energy are boundless – this succinctly pinpointed the problem as that description would remain apposite for far too long. Chapman never really did grow up.

Most of Chapman’s cricket in 1923 and 24 was at club and minor county level whilst he set about acquiring the residential qualification he needed to play for Kent. He was however still sufficently well thought of to be invited to play for the Rest in the 1924 Test trial. He contributed two fine innings of 64 not out and 43. He was selected after that for the first two Tests against that summer’s South African tourists, who proved to be no great challenge for the full might of England. Chapman scored just eight in his only visit to the crease. Sadly for him he missed the rest of the series after being injured in a road traffic accident. He was riding a motorcycle at the time, wearing a long coat, the tails of which caught in the rear wheel throwing him from his machine.

The immediate consequence of his injuries was that Chapman missed a large part of the rest of the 1924 season, and he ended it with just 561 runs at 31.16 without a century. Despite that, and still having never played a Championship match, he was selected for the party to tour Australia that winter to, it seems, universal approval. He did save the best till last, an astonishing display of forcing cricket for the Rest of England against the Champion County (Yorkshire) in the then traditional finale to the season, but even with that it is surprising that no real reservations seem to have been expressed. Two crushing series defeats since the Great War and the perceived need for new blood in order to defeat the Australians was clearly recognised as being paramount.

Included in the side for four of the five Tests Chapman didn’t quite come off. He always made a start, not once in his seven innings being dismissed in single figures, but on the other hand there was just one fifty, 58 in the third Test. The former Australian skipper Monty Noble, by then in the press box, summed Chapman up rather well, I have no fears for his future if he can restrain his irresistible desire to bang everything for four or six as soon as he begins his innings. The scoreline was 4-1 to Australia, so a third consecutive drubbing.

Finally in 1925 Chapman made his long awaited debut for Kent but, due to the calls of his employer there were just five First Class matches all season, and not even a half century. In 1926, when the Ashes had to be fought for again, he began the summer slowly but, with the sort of propitious timing he had shown for the Rest almost two years before he scored a superb 159 against Hampshire in his first appearance of the season for Kent, three weeks before the first Test. Handy scores either side of that for MCC and the South against the tourists meant that given his popularity there was little doubt but that he would be lining up against Australia again.

The first three drawn Tests produced scores of 50*, 15 and 42* for Chapman, so he must have been a little disappointed to be dropped for the fourth Test as Lancashire’s Ernest Tyldesley took his place. England’s skipper in the first four Tests was Arthur Carr of Notts, an amateur of course, but one with grit and determination, never afraid of unleashing at any opposition the twin menaces of Harold Larwood and Bill Voce. His had been an odd series, with just one visit to the crease in the four matches in which he scored 13, and reaction to his captaincy was mixed. The final Test was to be played to a finish and the selectors made four changes. Out went Carr, Tyldesley, Roy Kilner and Fred Root and in came Chapman, Larwood (for his second Test), George Geary and one of the selectors, 48 year old Wilfred Rhodes.

There was considerable controversy. First of all the announcement was clumsy, MCC reporting that Carr had offered to stand down. Carr however told the press he had done no such thing. The selection of Chapman to play was popular, but awarding him the captaincy was not. Many felt that the real captain would be Rhodes, but the Yorkshireman certainly disapproved of some of Chapman’s bowling changes, so it seems the youngster did run the show. Anyway it mattered little as a famous Test was won and on the balcony at the end Chapman shook hands with a taciturn looking Rhodes and beamed his famous smile at him. He didn’t let go until Rhodes reciprocated.

It might have just been that one Test as captain for Chapman, had he not had a stroke of remarkable good fortune in another road traffic accident late in the summer. Chapman was driving a car this time, and was journeying from Folkestone to Hythe when he was involved in a head-on collision with another car. Both vehicles were travelling at some speed and given the state of vehicle and road design in those days both drivers could easily have been killed. As it was the two men walked away from the accident. Chapman merely had a cut to his head. The other driver was uninjured.

In 1927 Chapman had his best ever season. He averaged more than 60 and scored 260 against Lancashire at Maidstone after Ted McDonald and Frank Sibbles had reduced the home side to 70-5. The following year his average almost halved, but after no Test cricket in the previous summer he was back as England captain against West Indies, who were playing their first Tests. England won each of the Tests by an innings and it was no surprise when Chapman was named captain of the 1928/29 Ashes tourists.

England retained the Ashes comfortably. They won the first Test by the huge margin of 675 runs and the second by eight wickets before coming out on top in the next two by narrow margins. Only in the final Test, from which Chapman was missing, did Australia salvage some pride. Chapman’s was the most powerful English batting side ever assembled, and Australia were in transition, but his captaincy must still have been a major factor, something clearly evidenced by England’s failure in the final Test without him. His batting was a disappointment, there being just one fifty, and that is often cited as the reason for his missing the last match, although the official line was that he was unwell. But if Chapman’s batting let him down his fielding didn’t. A brilliant one handed catch in the gully to dismiss Woodfull in the first Test was said to be the turning point of the series and Australian wicketkeeper Bert Oldfield described him as unquestionably the greatest all-round fieldsman I have seen.

After the tour ended Chapman spent some time in New Zealand with his wife’s family and did not return to England until July. On resuming his cricket he suffered a nasty knee injury so the season was ruined for him. Jack White and Carr led England against South Africa but Chapman was back for the 1930 Ashes series. There were some who did not approve. Chapman was not the man he had been. From his fighting weight in 1926 he had already put on two stone when he reached Australia in 1928, and he was bigger still in 1930. No longer was he the magnificent outfielder of his youth, although his close to the wicket fielding remained as brilliant as ever.

In the first Test Chapman’s golden streak continued as England took a 1-0 lead. Chapman scored 52 and 29, the first innings fifty being particularly valuable, breathing new life into an England innings that was stalling. The second Test at Lord’s finally brought the run to an end courtesy of, inevitably, Bradman. He scored 254 as Australia piled up 729-6 to bat England out of the game. The Ashes holders began the last day 207 behind with eight wickets standing. A rearguard action was surely called for, but that was not the Chapman way, and after an early let off when Bill Ponsford and Vic Richardson left a straightforward catch to each other he blazed away for two and a half hours for 121. It was by far his highest Test score. Of his five other scores over fifty the highest was that 58 in 1928/29.

Australia were left to score just 71 for victory, but Chapman wasn’t finished. At one point the visitors were rocking at 22-3, with Bradman gone by virtue of a miraculous catch in the gully by Chapman from a full blooded square cut. That low point marked the end of the excitement as Woodfull and Stan McCabe stood firm and took Australia to a seven wicket victory, but the crowd had seen a much better day’s cricket than they would have done if England had chosen to try and bat out time. The third and fourth Tests were drawn, the third dominated by 334 from Bradman and the fourth by rain and then all hell was let loose as Chapman was not only replaced as captain but dropped from the side for the deciding Test. The wheel had turned full circle from 1926.

There was an outcry in support of Chapman. Former England captain Arthur Gilligan described the decision as one of the biggest cricketing blunders ever made. His Australian counterpart Noble was scathing in his criticism of the selectors, describing Chapman as the one man in England capable of infusing life and spirit into the game. Maurice Tate wrote later that to a man the players who served under Chapman were disgusted by the decision. It was Bob Wyatt who had the unenviable task of replacing Chapman. He couldn’t emulate the man he replaced however, and Australia won by an innings – this time Bradman could only manage 232.

Prior to being deposed Chapman had already accepted an offer to captain England in South Africa the following winter. He fulfilled the committment and played his last five Tests. He was not a success with the bat, scoring just 75 runs in his seven innings, but as always he proved to be popular with the hosts and a fine ambassador for English cricket. He arrived back in 1931 and finally captained Kent. There remained a few knowledgable pundits who felt Chapman should still be England captain, but no one could ignore the fact that his mobility was in rapid decline, as was his batting. He played on for a few years more for Kent, and last appeared in a First Class match as late as 1939, but he left the glory days behind at Lord’s in 1930.

What was Chapman’s legacy? Gilligan always championed his cause, once listing what he described as 15 characteristics of a great captain and declaring Chapman the only man he knew who had all of them. Oldfield thought him the best he had seen. Rhodes agreed, a startling comment from the gruff Yorkshireman, but he would add the explanation that was only because Chapman always did as he was told. It was an odd remark from a man not given to cracking jokes, particularly given events at the Oval in 1926, but even if he did not always take their advice Chapman would listen to his senior men, something not all amateurs did.

More telling perhaps than the Yorkshireman who played with Chapman just the once was the view of his Kent colleague for so many years, Les Ames. The wicketkeeper batsman felt Chapman lacked tactical acumen and expressed the view that his greatest talent as captain was his skill at man-management and his ability to bring out the best in others. ‘Crusoe’ Robertson-Glasgow was also a great admirer and wrote His captaincy, like his batting, was natural. It was founded on quick perceptions, a wide knowledge of human nature, and a happiness of disposition. – it seems he had a degree in people half a century before Mike Brearley’s admirers made the phrase popular.

As the thirties wore on Chapman’s appearance changed markedly. Out went the physique that looked like it should be on an Olympic podium, and in its place was a sadly bloated and musclebound man hurtling towards an early middle age. A surfeit of good living and particularly far too much of his employer’s products had done the damage. Undoubtedly an alcoholic, as time moved on the admirers started to melt away, and on occasions the once great cricketer became an embarassment to those loyal friends who remained.

By 1942 Chapman’s wife could take no more and the once golden couple separated. When Mrs Chapman returned to New Zealand in 1946 Chapman made his final move, to the home of a friend who was the steward of the West Hill Golf Club near Woking in Surrey. The decline continued, not aided by arthritis that by the end had rendered him all but immobile. Shortly after his 61st birthday Chapman fell at home and fractured a kneecap. He was admitted to hospital but did not survive the surgery that his doctors advised was necessary.

In the manner of the times the press were kind to Chapman, describing a passing following a long illness and making no mention of his sad decline. More realistic were the views of the former Mrs Chapman, who commented to her late husband’s biographer that he must have died a very sad man. The passing of an England captain inevitably brought forth a stream of tributes. The “right” things were said by those who knew him and cricket briefly remembered Percy Chapman, but to this day he seems to be regarded as something of a skeleton in the game’s cupboard, which strikes me as very sad. It is unfortunate that he travelled a road so often trod by illustrious sportsmen, George Best, Brian Clough and Paul Gascoigne being three names that immediately spring to mind. But his was a prodigous talent, his achievements remarkable and he seems to have been as genuinely likeable and personable a man as has ever lived.

Interesting read as usual. Thanks. Q? Wasn’t Chapman the English manager of Jardine’s side during the Bodyline series?

Comment by JBMAC | 12:00am GMT 15 January 2015

[QUOTE=JBMAC;3389734]Interesting read as usual. Thanks. Q? Wasn’t Chapman the English manager of Jardine’s side during the Bodyline series?[/QUOTE]

Pelham Warner was manager on the 32/33 tour.

Another good read, thanks

Comment by Midwinter | 12:00am GMT 15 January 2015