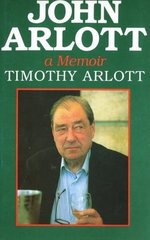

John Arlott – A Memoir

David Taylor |Published: 1992

Pages: 223

Author: Arlott, Timothy

Publisher: Andre Deutsch

Rating: 4 stars

I only caught John Arlott’s commentaries on Test Match Special at the end of his career, and I know many younger fans regret not hearing him at all, but I can remember thinking that he sounded like nobody else on the radio. I suppose nowadays he would be an impressionist’s dream but I don’t remember anyone tackling him at the time, and even Rory Bremner only came close to capturing that rural North Hampshire accent. I didn’t know anything about his writing or journalism at the time; I only discovered that side of him much later. I did read a biography of him a few years ago but this is something quite different, a collection of personal memories by his second son Timothy.

Writing a year after his father’s death in 1992, Tim Arlott didn’t write, and clearly didn’t want to write, a book about cricket, or broadcasting. That much is evident from a glance at the index – one mention of Brian Johnston, and none of Christopher Martin-Jenkins or Bill Frindall. He didn’t write about life in the Test Match Special box for the simple reason that he wasn’t there, and everything in this book is a first-hand account of life in the Arlott household. There is an element of biography as well; the reader is taken through John Arlott’s early life in Basingstoke, his years as a policeman in World War Two, and the series of happy events that led to his becoming a household name in broadcasting – not just on cricket by any means. There was an element of ‘right place, right time’ about his rise to prominence but it was by no means just serendipity – as Tim puts it, ‘at that period of his life [the mid-1940s] he was beating on so many doors at the same time that it was just a question of which one gave way first.’ Covering England’s tour of South Africa in 1948-49 left him with a lifelong detestation of apartheid, which in turn no doubt influenced him in helping Basil D’Oliveira establish himself in England. He spoke memorably and with total commitment in favour of cancelling the 1970 tour. A stop in Sicily introduced him to wine, not a drink enjoyed by the majority of British people at that time, and led to another lifelong passion.

What comes across is the portrait of a driven man, immensely hard-working (although some tasks he clearly considered women’s work) and prepared to consume himself in a new interest to the exclusion of all outside interference. If he often looked lugubrious in later years he had good reason – the death of his son Jim in a road accident on New Year’s Eve 1965 was something he mourned for the rest of his life, and it was followed by the death of a baby daughter and his adored second wife. There is a good deal of tragedy in the Arlott story but the tone is lightened by a series of wonderful stories, many of a surprisingly bawdy nature. I should add that most of the worst misbehaviour was down to his friends and associates rather than the man himself. His friendships with the likes of Dylan Thomas, John Betjeman and Kingsley Amis – he was just as much at home with literary types as he was with cricketers – are described entertainingly and never come across as name-dropping. Arlott became more cantankerous as the years passed, he could be exasperatingly stubborn, and clearly imbibed far more than was good for him. Tim Arlott gives an honest, warts and all account of these flaws but tells his father’s story with tremendous affection and admiration nonetheless. Highly recommended.

Leave a comment