Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets

Martin Chandler |Published: 2012

Pages: 256

Author: Quelch, Tim

Publisher: Pitch Publishing

Rating: 4 stars

I had the pleasure last year of reviewing Guy Fraser-Sampson’s Cricket at the Crossroads, a survey of English cricket and English society between 1967 and 1977. This book by Tim Quelch is, in some ways, a prequel, comprising as it does a not dissimilar look at the immediate post-war period, 1945-1959.

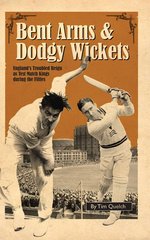

The front cover of the book uses a photograph of Kennington Oval, judging by the large crowd taken on a sunny Test Match Saturday, as a backdrop for images of two of England’s iconic figures of the period, Fred Trueman and Denis Compton. The title refers to two of the great controversies of the time, of which the former came to a head in Australia in 1958/59, when four Australian bowlers were widely accused of throwing, as well as at least one Englishman, and the latter at Old Trafford in 1956 when Jim Laker became one of the game’s immortals.

The blurb on the rear cover gives a flavour of what the book is about, although as ever the bibliography inside makes that clearer. Amongst the references to countless cricketing biographies, autobiographies and tour books there are some of the seminal works on the social history of the period by Anthony Sampson and David Kynaston, as well as my favourite ever novel, John Wain’s Hurry on Down. Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim , John Braine’s Room at the Top and Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning are other works of fiction that are noted. And if that doesn’t give the game away then the appearance of the title of John Osborne’s era-defining play Look Back in Anger, most certainly does.

Moving from introducing the book to reviewing it is rather trickier as Quelch has a difficult balance to strike in the 250 pages available to him. He has as many as 21 Test series to cover and, with an incidental social history of Great Britain to include as well, runs a very real risk of Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets being, to use that well known cricketing idiom, neither one thing nor the other. So there is nothing like a full account of any of the series involved, although all are treated in much the same way with a brief description of the matches, covering in the main the talking points that arose. It really is a case of blink and you may miss something, so this is certainly not a book that lends itself to being skim read.

Occasionally the cricket becomes inextricably entwined with the changing social order and this is where Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets is at its best. The age-old distinction between amateur and professional was still in place throughout the 1950s, but by 1959 it was on its way out, and that is a constant theme. The appointment of Freddie Brown as England captain in 1949, and his skippering the party to Australia in 1950/51, is a curious glimpse at a bygone age. That 1950/51 Ashes series also highlights one of the dangers this sort of book faces, in that by space not permitting a sufficiently detailed examination of issues a wrong or incomplete impression can be created. Denis Compton undoubtedly had problems with his famous knee injury in that series, and he missed one Test and in the other four had as bad a series as any major batsman has ever had, averaging just seven. Quelch dutifully highlights the issue, but there was rather more to it than England carrying a half-fit superstar, as outside the Tests “Compo” recorded four centuries and averaged more than 90.

If I had to criticise Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets it would be the absence of any contemporary input from any of the players of the period, and the slight tinge of disappointment that creates is only heightened by the fact so few of the main protagonists remain with us. I am sure the observations of any or all of Tom Graveney, Frank Tyson, Bob Appleyard or Brian Close, and in particular their recollections of the state of the nation, would have enhanced the book considerably, even if the publishers would have had to accomodate the use of rather more paper.

But whatever faults Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets may have, and in reality to be perfect it would have to the weightiest tome on the game ever produced, it is one of the most enjoyable cricket books I have read in a long time. The best measure of its success is that its overriding frustration for me was that it did not, when quoting from other works, give the relevant page numbers. Time and again the anecdotes that I read aroused a desire for further information that, without a more detailed reference, I could not have found without there being many more hours in a day than there actually are. So in conclusion I would unhesitatingly recommend Bent Arms and Dodgy Wickets, with the caveat that anyone who reads it can expect to get drawn into trawling through Ebay and book dealer’s catalogues in a bid to learn more about the myriad of cricketing and other issues it throws up – if it is of any consolation few of the essential books are either rare or costly, so there will be no financial pain.

Leave a comment