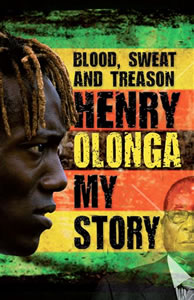

Blood, Sweat and Treason

Martin Chandler |

On 10 February 2003 two narrow strips of black insulating tape, worn as armbands by two International cricketers, brought the plight of the Zimbabwean people home to the world more starkly than anything said or done in the previous twenty years. Sporting contests, where raw emotion is often close to the surface, are an ideal vehicle for the protester and so it was to be for Henry Olonga and Andy Flower, the two cricketers involved, as the cricket world listened to their plea.

No sane person could suggest that the cause that Olonga and Flower championed that day in Harare was not a just one. It was one of those occasions when millions of consciences were pricked and a conflict of emotions felt by many. I recall to this day the admiration I felt for the two men, who in truth I knew little about, coupled with the embarrassment, which persists to this day, that the government of the country I live in seems so reluctant to lend the degree of support it surely should to the beleaguered population of a nation that until 1965, in theory at least, it took responsibility for.

In 1968 Tommie Smith and John Carlos, with their Black Power salute during the medal ceremony for the mens 200 metres at the Mexico Olympics, made a non-violent protest that reached all corners of the globe and which, perhaps, is in part responsible for the fact that within their lifetimes their countrymen elected a black president. It was only the cricket world that heard Olonga and Flower’s message, at least initially, and we do not yet know when the nation of Zimbabwe will finally match the hopes and dreams that they have for it, but we do know that, unlike Smith and Carlos, the two Zimbabweans risked their lives by the wording of their plea and the manner in which they made it. The full text of what was said was:

“It is a great honour for us to take the field today to play for Zimbabwe in the World Cup. We feel privileged and proud to have been able to represent our country. We are however deeply distressed about what is taking place in Zimbabwe in the midst of the World Cup and do not feel that we can take the field without indicating our feelings in a dignified manner and in keeping with the spirit of cricket.

We cannot in good conscience take to the field and ignore the fact that millions of our compatriots are starving, unemployed and oppressed. We are aware that hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans may even die in the coming months through a combination of starvation, poverty and Aids. We are aware that many people have been unjustly imprisoned and tortured simply for expressing their opinions about what is happening in the country. We have heard a torrent of racist hate speech directed at minority groups. We are aware that thousands of Zimbabweans are routinely denied their right to freedom of expression. We are aware that people have been murdered, raped, beaten and had their homes destroyed because of their beliefs and that many of those responsible have not been prosecuted. We are also aware that many patriotic Zimbabweans oppose us even playing in the World Cup because of what is happening.

It is impossible to ignore what is happening in Zimbabwe. Although we are just professional cricketers, we do have a conscience and feelings. We believe that if we remain silent that will be taken as a sign that either we do not care or we condone what is happening in Zimbabwe. We believe that it is important to stand up for what is right.

We have struggled to think of an action that would be appropriate and that would not demean the game we love so much. We have decided that we should act alone without other members of the team being involved because our decision is deeply personal and we did not want to use our senior status to unfairly influence more junior members of the squad. We would like to stress that we greatly respect the ICC and are grateful for all the hard work it has done in bringing the World Cup to Zimbabwe.

In all the circumstances we have decided that we will each wear a black armband for the duration of the World Cup. In doing so we are mourning the death of democracy in our beloved Zimbabwe. In doing so we are making a silent plea to those responsible to stop the abuse of human rights in Zimbabwe. In doing so we pray that our small action may help to restore sanity and dignity to our Nation.

Andrew Flower – Henry Olonga”

Henry Olonga’s autobiography has just been published in the UK and Cricket Web were fortunate enough to receive an advance copy. You can see what I thought of the book here. More importantly Henry and his publisher have kindly allowed us to reproduce Chapter 1 here. The Chapter begins by quoting the prescient observation of the 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

“Tell your son that he needs to get out of Zimbabwe before the World Cup ends.”

With these words my life in my homeland came to an end. I already knew that the secret police were bugging my phone and I was pretty sure they were following me too. I’d been dropped from the Zimbabwean team and banned from taking to the field even to distribute drinks. I had received death threats by e-mail; I’d been intimidated by members of Mugabe’s infamous youth militia and warned that members of the government were seriously displeased. Now my father had received this urgent message from a contact within the central intelligence organisation. It was a warning based on concrete information.

When Andy Flower and I had made our black armband protest a few days earlier at the 2003 World Cup cricket match between Zimbabwe and Namibia, mourning the death of democracy in our country, I’d been really energised. Over a number of years I had come to know the full extent of Mugabe’s atrocities against the Zimbabwean people and to finally take a stand against him had been the biggest challenge of my life. But now I was really concerned, even a little scared.

I knew what could happen to people who crossed Mugabe. I knew that he and his henchmen were alleged to be responsible for the torture, rape and murder of hundreds and thousands of my countrymen. I felt I could be carted away at any minute and never be seen again. I knew there were rumours that people had quite literally disappeared by being thrown into baths of sulphuric acid. Maybe I would just be imprisoned. But Zimbabwean prisons are amongst the worst in the world. They are brutal, disease-ridden places where beatings and rape are part of the daily routine. In a country where one in four people has AIDS, as far as I was concerned prison meant death.

Of course Andy and I had been aware that the consequences of our actions could potentially be life-changing. I had hoped they would not be, but now it was clear to me that my life was in danger. In fact probably the only thing keeping me alive was the presence of foreign journalists covering the World Cup here in Zimbabwe and a watching world. Allowing the presence of the world’s press had been a stipulation in awarding Zimbabwe the World Cup, and many of the world’s top news reporters had taken the opportunity to gain access to the country and get an insight into what was really going on in our increasingly troubled and controversial nation. But what would happen when they left? I had to get out. But how? Unless I made a run for the border, my only chance was Zimbabwe qualifying for the Super Sixes of the World Cup which were to be held in South Africa. Mugabe’s people would never be able to stop me leaving then, it would be too obvious if I didn’t turn up for the second round of matches.

OK, so that was all great in theory: there was only one problem. Between me and that flight to Johannesburg and freedom was the small matter of the mighty Pakistan, one of the great teams of the tournament, boasting a host of world-class cricketers including Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Saeed Anwar and others. To get to the Super Sixes we needed at least a draw against Pakistan but who draws one day matches? Since they themselves needed a win to stay in the World Cup, to say it wasn’t going to be easy would be a massive understatement.

To be honest, in the run-up to the game, cricket was the last thing on my mind. I had been dropped from the team after the black armband protest anyway by the furious officials of the Zimbabwean Cricket Union, as it was called then. I had also received an e-mail from a well-wisher who said a woman who worked in a government minister’s office had a warning for me. In it she warned me that the minister had been overheard in his office saying, “This Olonga guy thinks he is so clever. Just wait until after the World Cup is over. He won’t be so clever then. We will sort him out.” And a few days after the protest I had been speaking on the phone when I’d heard a third voice on the line: they were clearly tapping my calls. I started seeing secret police everywhere. “How long has that car been following us?” “Who’s that man lurking in that doorway?” One day in practice in the nets I joked about something and Heath Streak said, “You won’t be laughing when they’re putting electric shocks through your balls!” Then in the end my father got the message that I needed to get out.

I was in a daze. All sorts of different people were saying all sorts of different things to us – we were going to be charged with treason, warrants were going to be issued for our arrest. Treason? They could call me anything they wanted other than a traitor. We were making a stand for our country’s future: how could we be traitors? To this day I don’t know if I was ever formally charged with treason, but I do know that the penalty for treason in Zimbabwe is death and that there is no right of appeal. Mugabe has charged many an opponent with treason and very often it is a gruelling process to receive justice.

So why did I do it and how did I get here? The famous quote from Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing” rang through my mind. I would never call myself a good man but people had to stand up against this evil regime.

During all this time I never once doubted that what we had done was the right thing. I never once regretted the decision to make a stand. In the years leading up to our protest I had read dossiers that told of unspeakable atrocities being carried out in the name of Mugabe and I had spent hundreds, if not thousands, of hours on the Internet trying to get a feel for how the outside world viewed my homeland. I had been brought up to believe that my president was a hero, but the rest of the world viewed him very differently and it had become clear to me that the foreign view was most accurate. That is a pretty dreadful thing to realise about your country and its politicians.

It was this journey of discovery that had led me to the place where I was now, fearing for my life and the lives of my family. On the eve of the Pakistan match I really didn’t know what I was going to do, and then I had an encounter in the foyer of the team hotel in Bulawayo that was final confirmation for me that if I didn’t get out of the country I really was finished.

As I was preparing to leave for the match, I was chatting to an old friend when a man called Ozias Bvute, a big noise in Zimbabwean cricket, came over and butted in. He was an administrator and had played a key role in the integration taskforce employed to make sure more black players made it into the Zimbabwean team. He was a powerful man in the game. My friend looked him in the eye and said, “Ozias, I know you ZANU-PF guys, and Henry is my friend and I don’t want you to mess with him.”

ZANU-PF is an extreme political party in much of its ideology. If someone not a member of the party was accused of being one they would surely protest. But Bvute didn’t deny he was a member: all he did was laugh. There was something about his laugh: it was cold and heartless. His mouth laughed but his eyes held no humour. He was saying, “Oh no, Henry’s a part of our plans for a very long time into the future,” but I sensed that he wasn’t being honest. If he was ZANU-PF then perhaps he knew that the minister had it in for me as soon as the World Cup was over. The second I heard him laugh I knew my time was up. If there had been the slightest doubt in my mind up to that point, now it was gone. If there was a single defining moment for me, that was probably it. I find it almost impossible to describe how unsettled I was by his insincerity. I knew that I simply had to get out and that I might never be able to come back.

So it came down to our match against Pakistan: my life-or-death game, a game in which I wasn’t even going to be playing so I wouldn’t even have the opportunity to play the match of a lifetime to save my skin.

The night before the match I was in my hotel room in Bulawayo and I got down on my knees and prayed. “God, I think I heard you on this,” I said. “I think this was the right thing to do, to take a stance against this tyrant. I need your help to get out of Zimbabwe.” It was a short prayer, simple and to the point. He had helped me before and I believed that if He thought it was right to do so again then He would step in one more time.

Then I went out for dinner with some friends and when I returned to the hotel one of my teammates, Craig Wishart, asked if I had seen the weather forecast. I didn’t pay too much attention. Instead I went upstairs to my room and went to sleep. But when I woke up the next morning and turned on the TV weather report, lo and behold a cyclone had built up off the coast of Mozambique.

We got to the ground and although I was not playing I spent my time geeing up the players, telling them they could win this game. Please win this game! We bowled 14 overs and had Pakistan 73 for 3, and then it started to rain. From the Queens Ground in Bulawayo it is usually possible to see far into the distance towards a place called Ascot, famous for its racecourse just like the place of the same name in England. There is a huge building at the course that stands out for many miles, but when it rains heavily you can’t see it from the cricket ground so it’s a good barometer for how likely it is that play will resume soon. I had been keeping my eye on Ascot and it had disappeared. The rain was still falling in Bulawayo. Not too heavy, but enough to stop play. It kept coming in sheets. Wave after wave after wave of this rain kept coming. I kept glancing over in the direction of Ascot, hoping of course that it would not reappear.

As the rain continued and continued, my sense of fear and trepidation lessened and lessened. Mid-afternoon arrived and the umpires announced that they were abandoning the game. The match was a draw. Sensationally, Pakistan were out of the World Cup and we had got the point we needed and were through to the Super Sixes. Within a short time of play being called off for the day, the clouds disappeared and the sun peaked through briefly. Pakistan may have felt they had been undone, but not me. I believed my prayers had been answered. I had been given the chance to get out of Zimbabwe and preserve my life.

I had been running all sorts of ideas through my head about how I was going to smuggle myself out of the country, usually involving a late-night dash to some remote border post, to Botswana or Zambia. Had we been ejected on that day, who knows whether they wouldn’t have sent someone to pick me up straight away. Maybe the police would have come for me in the changing rooms, I don’t know. This is Zimbabwe: there’s a news blackout, so there’s no story. There would have been no foreign journalists in Zimbabwe any more with the World Cup switching completely to South Africa. Even if there had been anyone to ask the questions, what would the answer have been? “What happened to Olonga?” “Oh, we don’t know?” End of story.

But that hadn’t happened, because the rain had come. You can make of this what you will. It might have been coincidence but at the time I was convinced that it was divine intervention and I still believe that to this day. God decided that He had plans for me, and they did not include being thrown in a rotten, stinking prison cell, being beaten to within an inch of my life, or worse. I’m sure there are a lot of people who will read this and think, “This guy’s nuts: what’s he on about with divine intervention and isn’t he exaggerating the consequences?” But as coincidental as it may appear to a lot of people, for me that was an answer to prayer. Whether it was an act of nature or an act of God I will not endeavour to explain, because I cannot adequately give an answer that will appease everyone. But what I know is that I was in trouble, I needed something extraordinary to happen, I prayed and it happened. That enabled me to get out of the country and may well have saved my life.

Now we were still in the World Cup and on our way to South Africa, the authorities couldn’t touch me. I knew it and they knew it. I went home to Harare. Days later I got on a plane to Johannesburg with the rest of my teammates, knowing that I had my ticket out. Beyond that I hadn’t a clue what was to become of me, but at least I had escaped the clutches of Mugabe’s murderous regime for now

Blood, Sweat and Treason, is published by Vision Sport Publishing and the UK cover price is a penny shy of nineteen pounds. It is available, as the old cliche goes, at all good bookshops.

The piece that was reproduced from the book is extraordinary. Thank you so much for your time on the articles Martin.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 27 July 2010

Great Review Martin.

Comment by Sanz | 12:00am BST 27 July 2010

Excellent review.

Comment by GingerFurball | 12:00am BST 27 July 2010

Divine intervention or not, it’s an incredible tale. Can a greater consequence have ever rested on the outcome of a cricket match? Another tour de force, Martin!

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am BST 27 July 2010

That chapter is great i’ll be ordering a copy of this book when i get home. It is an interesting event and I’m sure unless you knew what was going on in Zimbabwe at the time, the outside world has no clue what could have happened to him at the time.

Comment by outbreak | 12:00am BST 27 July 2010

Really like the title of his book actually. Fairly intriguing. Good review on the whole.

Comment by Himannv | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Good Review by Martin.

Would be a good read that book i am sure.

Comment by Cevno | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Excellent pieces Martin, the pair of them are terrific. 🙂

Have ordered my copy online, am very much looking forward to having a read of it.

Comment by Marcuss | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Amazing chapter. Wow. Talk about a meaningful match….

And we give thugs like Bvute a voice at the ICC table. Disgraceful.

Comment by silentstriker | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Good memory Jack 🙂

Cricket Web – Interviews – Henry Olonga

Comment by James | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Henry is a fantastic bloke – was very co-operative for the interview and gave some real depth with his answers. Because of his stance in the 2003 WC, sometimes his cricket ability was underestimated – was certainly a very capable fast bowler.

Good cricketer and even better human being – glad to see he is enjoying life and making the most of his opportunities. Only deserves good things.

Comment by Andre | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Great stuff, Martin.

Am I right in saying that Andre (former staff member) once conducted an interview with Henry? Is there still a link to that?

Comment by Jack | 12:00am BST 28 July 2010

Henry Olonga’s autobiography was fortunate enough to receive an advance copy. You can see what I thought of the book.

As we are aware that hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans may even die in the coming months through a combination of starvation, poverty and Aids.

Comment by Daniel Parker | 12:00am BST 30 July 2010

That first chapter is gripping.

Would love to get a copy of the book, certainly would be an interesting read. And is Olonga playing in Zimbabwe’s new domestic set-up?

Comment by Fiji-Bati | 12:00am BST 1 August 2010

Henry is alive and well and living in West London but he won’t go back to Zim if for no other reason than he’s currently effectively stateless, as the Zim authorities won’t even consider renewing his passport unless he goes back there to do it in person which, understandably, he has no intention of doing at the moment.

Comment by Martin Chandler | 12:00am BST 1 August 2010

Mr Chandler in fine form atm, it keeps coming with his and David’s review of Frith’s new book, which will be up tonight.

Comment by Sean Ehlers | 12:00am BST 1 August 2010