A Nation Mourned – The Story of the Wayside Preacher

Martin Chandler |

Over the years there have been three autobiographies from Garry Sobers. The first, Cricket Crusader, appeared in 1966 and seems, from an acknowledgment at the beginning of the book, to have been ghosted by RA Martin, a man who, to the best of my knowledge, does not appear to have been involved in any other cricket books. Brian Scovell, who in 1988 assisted with Twenty Years at the Top, and Bob Harris who did the legwork for the 2002 My Autobiography, are much more familiar names, particularly Scovell.

Sobers is one of the greatest cricketers in the history of the game, and to illustrate that it is necessary only to look at the exercise carried out by Wisden in its 2000 edition to establish the five greatest players of the twentieth century. Unlike Sir Donald Bradman Sobers failed to make a clean sweep of all 100 voters, but he was nominated by 90, well ahead of the other three men selected, and as many as 77 votes clear of the next all-rounder.

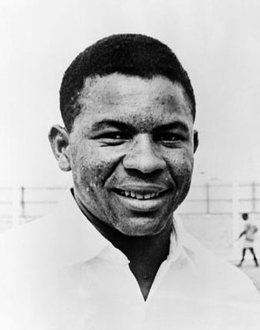

In Twenty Years at the Top Sobers said of O’Neil Gordon Smith, better known simply as “Collie”, that he had the ability to become a better all-rounder than me a judgment which, given Sobers’ pre-eminence in the field, deserves a closer examination. For reasons that I will explain Sobers is not well-placed to make an objective assessment of Collie the all-rounder, but the full potential of the young Jamaican who died in September 1959, in tragic circumstances at just 26, was undoubtedly left unfulfilled.

Sobers himself has never let Collie be forgotten and there are long passages about him in both Cricket Crusader and Twenty Years at the Top. The memory had faded not one iota by the time My Autobiography appeared and in that book the very first chapter, described as a prologue, is devoted to the man of whom Sobers had written more than thirty years previously he was three years older than I, much smaller in physical size, but he had the heart of a giant, an unquenchable ecstasy of spirit, a joyous nature and unmatchable zest for living – and for cricket.

In 1933 the Jamaican Ivan Barrow had been the first West Indian batsman to score a century in a Test in England. In 1952 he said of Collie; He is the best natural cricketer we have had out here since the arrival of Weekes, Worrell and Walcott, and if there is ever to be another Headley, Smith is the one.

It was to be three years on from Barrow’s comment before Collie made his First Class debut in 1955 against Trinidad. In the first of two matches against the Trinidadians in February 1955 his achievements were modest, but in the second he scored an unbeaten 58 in just 57 minutes to claim victory after his team had fallen well behind the clock in pursuit of a victory target of 253.

A little over a month later the Australians, their 3-1 Ashes defeat by Len Hutton’s England having been completed just a few weeks before, began a five Test tour of the Caribbean. Their opening match was against Collie’s Jamaica and the tourists fielded a side top heavy in bowling. Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall were not perhaps the power they had been in the late 1940s, but were still a fine opening pair. Their old back-up Bill Johnston was also playing as was Alan Davidson. If that were not enough that pace attack was augmented by the off spin of Australian skipper Ian Johnson, and the wrist spin of Richie Benaud. After the batsmen who had been so roughly treated by Frank Tyson had regained some confidence with 453, Collie taking four wickets, the home side slumped to 81-5 before an historic stand of 277 between Collie and Alfie Binns turned the match around.

Australian writer RS “Dick” Whitington, a good enough batsman to have played in all five of the Victory Tests of 1945, was sufficiently impressed by Collie’s 169 to write I have attended the birth of so many embryo Bradmans that these confinements tend to become monotonous. But Smith’s approach to a crisis is so Bradmanesque that it is more than possible that at last we have seen the genuine article. In the face of such fulsome praise it must be accepted that Collie lost his way a little in the years that followed, but it is forceful evidence for those, like Sobers, who contend that he was a much better cricketer than his raw statistics suggest.

Collie’s next First Class match, his fourth in all, was the first Test at Sabina Park in Kingston. The Australians posted a formidable 515 on winning the toss and when Collie arrived at the crease the home side were struggling on 101-5. Sadly for West Indies he could not dig them all the way out of the hole that they were in, but the 44 he contributed to a stand of 138 with Clyde Walcott briefly raised hopes that the follow-on might be avoided. In the second innings Collie was promoted to number three and, before succumbing to the second new ball, scored a superb 104. His colleagues could not match him however and Australia were comfortable winners by 9 wickets.

The second Test was drawn but Collie ran out of luck and was dismissed for a pair. In the first innings he had to sit in the pavilion while Walcott and Everton Weekes added 242 before falling to the second delivery he faced from Benaud, a top-spinner that trickled onto his stumps from his bat. In the second innings he was caught by wicketkeeper Langley from a delivery by paceman Ron Archer, although many thought it a questionable decision.

A harsher decision still was to follow as the selectors caused an outcry before the third Test, first by dropping spin twins Sonny Ramadhin (although he was recalled before the game started) and Alf Valentine, and then poor Collie despite his two hundreds in five innings against the tourists. Whitington compared the decision to that made by the Australian selectors in 1928 when they dropped Bradman and said ..the dropping of Smith suggests that the selectors are envious of the ignominy the 1928 panel have borne for 27 years. Another famous Australian writer, Ray Robinson, was equally scathing his comment being that selection methods were based on the oranges-and-lemons nursery rhyme principle of chip-chopping the head off the last man to fail. Predictably the sports editor of the Jamaican Daily Gleaner, LD “Strebor” Roberts was livid. I regard the omission of Smith as an extraordinary piece of injustice to the youngster.

The man himself by all accounts took the decision philosophically, and he was back for the fourth and fifth Tests. He made no major contribution to either game, and it is difficult to imagine that his treatment by the selectors did anything other than adversely affect his confidence.

Runs did not flow from Collie’s bat in his next series either, in New Zealand in 1955/56, as he managed just one half century in the four Tests, although with 13 wickets at 18 it was to prove his most successful series with the ball. He was however back to his best the following year as he scored three centuries in the four domestic First Class matches he played to keep himself at the forefront of the selectors’ minds for 1957.

In that summer following the Suez crisis the West Indies toured England where, on their last visit in 1950, they had humbled their hosts with some superb cricket. Seven years on the stars of John Goddard’s team were all back, but they found a very different England waiting for them and Peter May’s side took the series 3-0, and were well on top in the drawn games at Edgbaston and Trent Bridge. The big names all disappointed, Weekes, Worrell, Walcott, Ramadhin and Valentine failing to live up to expectations, and Sobers struggled as well. The tourists leading runscorer in the Tests was Collie, and he had the best average as well. He lacked consistency but with 161 and 168 in the two drawn games he played two defiant yet thrilling innings. He was immensely popular and was deservedly selected as one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year in the Almanack’s 1958 edition.

The following home season saw a visit from Pakistan and, with three half centuries and an average of 47, Collie began to find some consistency. He might have done even better had it not been for Sobers’ then world record 365* preventing him from even getting to the crease on his home ground at Sabina Park.

The final Tests of Collie’s career came in the following winter of 1958/59 on the sub-continent. Between November and February there was a comfortable 3-0 win in India in a five Test series. The final, drawn Test, was the most successful all-round performance of Collie’s career as he recorded his fourth and final Test century and took eight wickets, including 5-90 in the Indian second innings as the West Indies pushed in vain for a fourth victory. In Pakistan the series was lost 2-1 amidst much unhappiness amongst the visiting players about the standard of the local umpiring. Collie’s main role in the series seems to have been helping his teammates, and particularly Sobers, to deal with the perceived injustices that resulted from that.

For the 1958 English summer Collie had, following his impressive performances with the West Indies the previous year, returned to play for Burnley in the Lancashire League. He only had two seasons at the club but made a huge impression. In his 1992 published history of the Lancashire League David Edmundsen wrote; Of all the professionals who made up that sparkling dynasty of cricketing excellence in the League’s Golden Age, the name of Collie Smith is special. The mention of Collie’s name prompts a sharp intake of breath, a pursing of the lips and a far-away look in the eyes of anyone who saw, or played with or against him.

There were two particular feats that Collie was remembered for, each in their own way equally remarkable. Statistically the most significant was a triple century, an unbeaten 306, against Lowerhouse in June 1959. The innings was spread over three evenings and a record victory by 376 runs was the result. Collie’s other achievement, and the one that gave him the greater pleasure, was the biggest hit ever seen at Burnley, a drive that ended up in the centre circle of the neighbouring ground of Burnley FC, in those days one of the most powerful clubs in the land, who were destined to be League Champions within 12 months.

The penultimate round of matches for the Lancashire League season of 1959 were played on Saturday 5 September. The following day Collie, Sobers and fast bowlers Tom Dewdney and Roy Gilchrist were due to play in a charity match a few miles west of London at Staines. The four West Indian Test players agreed to meet in the evening, following their games that afternoon, in order to drive south together. Eventually the others gave up waiting for Gilchrist and set off. Collie and Dewdney took their turn at the wheel before Sobers took over. At that stage Dewdney was in the passenger seat and Collie, choosing to catch up on his sleep, lay across the back seat.

It was on the main A34 trunk road, near the unremarkable Staffordshire town of Stone, that tragedy struck. At around 4.45am Sobers approached a bend and was confronted by the dazzling headlights of what turned out to be a 10 ton cattle truck. There was a head on collision. Sobers was unconscious briefly but ultimately the injuries he suffered, mainly to his left wrist and hand, did not prevent him being fit to face the 1959/60 England tourists. The career of Dewdney, who had been capped nine times, was to end a couple of years later, but he regained his fitness sufficiently to win a place on the 1960/61 tour of Australia, even if his form could not secure him a berth in the Test side.

Collie however, presumably as a result of the prone or supine position he had adopted on the rear seat, sustained a severe spinal injury and despite retaining consciousness for long enough to tell Sobers to attend to a distressed Dewdney, he soon slipped into a coma and died three days later. Such is the fickle finger of fate. If only Gilchrist had turned up on time, or if the trio had waited a little longer for him, or even if Collie had sat up rather than laid down, then cricket history would have been different. The Burnley Evening Telegraph said; Tears were shed by many Burnley people as news of the death of Collie Smith hit town. There was an eerie silence at Turf Moor for the final game of the season the following Saturday when, ironically, Burnley’s guest professional and main contributor to a comfortable victory, was Gilchrist.

Back home in Jamaica Collie’s popularity knew no bounds. He was a man of deep religious conviction hence the soubriquet that gives this feature its title. He had preached, along with England batsman David Sheppard (later the Bishop of Liverpool) at a special service at St George’s Church in Leeds on the Sunday of the Headingley Test in 1957. Most sources estimate that more than 60,000 people (the figure Walcott gives is 100,000) lined the streets of Kingston for his funeral, a figure which speaks as eloquently as any of the many tributes he received as to the esteem in which he was held.

Inevitably Collie’s death had a profound effect upon Sobers. Simply being at the wheel of the car when the accident happened would of course have been bad enough, but a subsequent fine for the offence that was then called “driving without due care and attention” gave him a weight he found difficult to carry, and which has remained with him ever since. Initially he nearly collapsed under the strain. Before the accident Sobers had been little more than a social drinker, but his grief caused him to start drinking heavily and a fear of sleep turned him into an essentially nocturnal man. In some ways those habits never left him but Sobers, as cricket history records, got a grip on himself and went on to become the great cricketer he is now remembered as. His rehabilitation began when, contrary to his worst fears, he received a hugely supportive reception on his next visit to Jamaica, and he vowed to, as well as making his own contributions to the West Indies cause, also score the runs and take the wickets that should have been Collie’s. He later wrote that Collie was with him for every single delivery of the 226 he scored against England in his first Test innings after the accident.

So what might Collie himself have become? Was the early comparison to Bradman really a sensible one? And what of Sobers’ assertion that Collie could have been a better all-rounder than him? I have already conceded that Sobers’ objectivity has to be questioned but it is impossible to say that of Whitington. His remarks were made back in 1955, and clearly therefore were not coloured by the later tragic events, nor by any nationalistic considerations, yet 26 is a fair number of Tests in which to play and an average of 31.69 is nothing special. However talented Collie was he could never have got near to Bradman’s cumulative records because of his approach to the game. A Bradmanesque single-minded pursuit of runs without taking risks was alien to his nature. Edmundsen’s book summarised him as ..the epitome of the cavalier cricketer, he always tried to hit his first ball for six. In 1957 he played in the traditional tour opener at Worcester, and his first scoring shot cleared the boundary, as indeed did his last, against TN Pearce’s XI at Scarborough four months later.

When Collie first came into the West Indies side the “Three Ws” were still at the peak of their powers, and he was allowed to play in his naturally exuberant style. I suspect that had he lived he would have become a slightly steadier player. I cannot imagine he would have changed his basic approach, but experience, and the responsibility of a place at the top of the batting order would have seen him become, through the 1960s, at least the equal of Conrad Hunte and Rohan Kanhai, and perhaps even Sobers as well. Walcott’s view was that ..he was surely destined to break some of the records of the Three Ws.

And his bowling? Collie began his cricketing life as a seam bowler and it was only when, at nearly 15, he saw Jim Laker bowling in 1948, that he decided to turn to the off spin that brought him 48 wickets at 33.85 in those 26 Tests. Off spinners, as a rule, mature late. Laker is perhaps not the best example as his early career was affected by the war, but at 26, the age Collie was when he died, his 27 Test wickets had cost him 37 runs each. The great Indian, Erapelli Prasanna, had just four victims at more than 40 runs each at the same age. Neither of the world’s current leading off spinners, Saeed Ajmal and Graeme Swann, had so much as played a single Test by the age of 26 and Sobers’ theory, that Collie was just beginning to develop his bowling at the time of his death, seems a sound one to me, particularly bearing in mind that, unlike those others I have mentioned, Collie was a batsman first and foremost. For a more unbiased assessment former England all-rounder Trevor Bailey described Collie as an ..off spinner of enormous promise with a teasing flight and a sharp break….everything suggests he would have become a front-line international spinner. Professor Keith Sandiford, one of the world’s leading cricket sociologists and statisticians, was amongst the crowd in the Barbados Test of 1955. Despite his unashamed admiration for his great friend Sobers, and what he admits is a great difficulty in viewing the great man’s abilities dispassionately, he says of Collie’s bowling in that match; He was easily the best of our spinners in a team that included Ramadhin, Sobers and Valentine.

In the aftermath of the funeral a timeless tribute was paid by Sir Kenneth Blackburne, then Governor of Jamaica; The name of Collie Smith will long live as an example not only of a fine cricketer, but also of a great sportsman. He will provide inspiration for our youth in the future. In the half century or so that has passed since those words were spoken Collie has not been forgotten, and as long as there is breath in Garry Sobers’ body, he certainly won’t be.

Fantastic stuff as usual tangy.

Comment by Uppercut | 12:00am GMT 2 March 2012

I recall a BBC Maestro program featuring Sobers when Smith’s name was brought up – Sober’s reaction led me to look into Smiths brief career. As a result this particular feature probably resonates to a greater degree than any of your features to date – I would have to rate this your best feature yet, though this may be akin to comparing K2 and Everest – lets face it, they’re both feckin huge!

Comment by chasingthedon | 12:00am GMT 3 March 2012