Bruce Harris – Bodyline Author

Martin Chandler |

Stephen Bruce Harris was born in Ireland in 1887, although he was brought up in Somerset. A career journalist he began that calling in the north east of England before moving to Birmingham. His writing was interrupted by the Great War, which Harris spent as a Lieutenant in the Fifth Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, primarily serving in the Middle East. He returned to Birmingham after the war, but in 1920 joined the staff of the Evening Standard in London and, moving to the capital, he spent the rest of his life living in Ealing.

The first position that Harris had with the Evening Standard was on its news desk before becoming a sports editor, and then the paper’s tennis correspondent. His career path changed markedly however in 1932 when his employer became the first English newspaper to send a journalist to Australia to follow an Ashes tour.

In May of 1932 a young EW ‘Jim’ Swanton was told he would be the man going. Swanton was only 25. A decent club cricketer who would go on to play three times in First Class cricket Swanton understood the game and in time became one of the giants of post war cricket writing. A man who strongly disapproved of Douglas Jardine’s ‘Bodyline’ tactics cricket history might have been different had he gone. As it was however a bad mistake in the middle of June cost him the chance. Having been dispatched to Leyton to report on the visit of Yorkshire to Essex Swanton watched Herbert Sutcliffe and Percy Holmes compile their record breaking opening partnership of 555. Last in the queue for the single telephone at the ground Swanton failed to get his copy back to the office in time.

It took some time for the decision to be made not to send Swanton to Australia, perhaps through a lack of alternatives but, in the end, it was decided to send the experienced newshound Harris, who was promptly dispatched to the end of season Scarborough Festival to start his crash course in cricket. Understandably bitter Swanton was, in his 1972 autobiography, critical of his colleague’s appointment. He described Harris as a very decent, conscientious fellow who knew nothing about cricket at all.

In his splendid book, Bodyline Autopsy, David Frith made his point rather cleverly in recognising that what Swanton said was true, but adding that Harris was, like many a tabloid scribbler skilful at concealing his ignorance. His means of doing that was to quickly establish a rapport with the England captain, Douglas Jardine. The Iron Duke was, of course, no fool himself and saw the importance from his point of view of having a friend in the press box.

There were only three English writers in Australia in 1932/33. Jack Hobbs was one, and whilst he did not approve of Jardine’s tactics he was not about to openly criticise his county captain. The other source of copy was the Reuters correspondent, former Australian skipper Warwick Armstrong. The Big Ship was not overly impressed with ‘Bodyline’, but was nonetheless the man who had unleashed the formidable pace attack of Gregory and McDonald on England a decade earlier so the English public were never going to attach to much credence to criticism from him. In any event the Reuters style tended towards neutrality and objectivity.

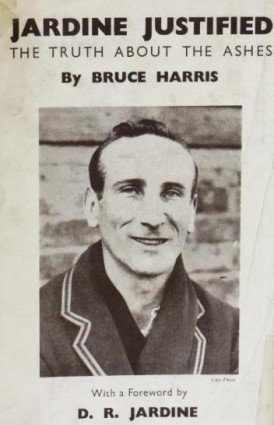

As for Harris the title of his post tour account tells the whole story of his attitude. Jardine Justified began with a reproduction of a hand written letter from Jardine, fulsome in its praise for Harris, followed by a considered foreword. The book is inevitably approving of Jardine’s tactics but is certainly not a bad read and set down a benchmark for Harris’s style of writing. He was not afraid to leave the cricket from time to time and look at other aspects of the touring experience.

The book was well reviewed. A delightful and valuable story according to the West Sussex Gazette and the Derby Daily Telegraph described it as first class reading. Harris’s former employer the Birmingham Daily Gazette referred to a fascinating account. In Australia Arthur Mailey, writing in the Sydney Sun, was not impressed with the backslapping exchanges between Jardine and Harris at the front of the book, but that apart his views were largely positive and Harris was no doubt delighted to see that no less a man than the former Test leg spinner complimented him on his understanding of the technical aspects of the game.

Harris was back in Australia in 1936/37. Again he wrote a book,1937 Australian Test Tour. Interestingly he once again had a foreword from the England captain, this time of course Gubby Allen, the man who refused to bowl ‘Bodyline’. Of Harris Allen wrote; he has been a very good friend to me – one wonders what Jardine would have made of that one? Harris’s publishers in 1937 were Hutchinson, the company who had published Don Bradman’s Book in 1930. The closest Harris came to writing any biographical work was to add a few chapters to that book to produce a second edition, and some competition for Bradman’s new book, My Cricketing Life, which also appeared in 1938.

In his late fifties by the time cricket resumed after World War Two Harris toured with England again in 1946/47, 1950/51 and 1954/55. There was a book each time and, in the case of the latter, a foreword from the England captain Len Hutton. Harris was clearly unable to persuade England’s captains in 1946/47 and 1950/51 to similarly contribute. Interestingly both men, Walter Hammond and FreddieBrown were veterans of the ‘Bodyline’ campaign, albeit Brown had not played in any of the Tests. Harris also wrote a book on the 1953 series, his first book on a home series, although for that one, assuming he was invited to do so, Hutton could not be persuaded to contribute.

Tour books were plentiful in the 1950s and the home series in 1955, 1956 and 1957 against South Africa, Australia, West Indies were all dealt with in books by Harris. In each of them he secured a foreword from England captain Peter May and in the first two one from the visiting captains as well, Jack Cheetham and Ian Johnson, notwithstanding that both men had their own books in the marketplace. Harris’s books on home series lacked the stories of the touring experience that marked his books from his trips to Australia so were rather less distinctive amidst what, in 1953 and 1956 particularly, was a crowded marketplace. In 1953, the year England finally reclaimed the Ashes Padwick lists ten tour accounts, with nine for 1956. Times changed quickly however and by 1957 Harris had the field to himself. His account of a disappointingly one sided contest was West Indies Cricket Challenge.

The final book from Harris was his only one from a genre other than that of the tour book. The True Book About Cricket, published in 1958, has an interesting title but the main eyebrow raiser, the use of the word True, is something of a misnomer. At that time the book’s publisher, Frederick Muller, had a whole series of The True …. books, which were aimed at a school aged audience. This was therefore a relatively modest (144 page) history of the game. A review in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News described it as containing a great deal of interesting historical information about the game. It is not a book I have personally seen, but if I see a copy I will certainly look at it if for no other reason that the reviewer’s later comment that the text is not enhanced by the illustrations,which lose their point through to an occasional tendency to be facetious.

Bruce Harris died at the age of 74 in October 1960. He had married late in life at 64 in 1951 but, despite his wife being twenty years younger than he was, she predeceased him by a couple years. According to Harris’s obituary in The Cricketer he had been ill for a long time. Given that there was a legacy in his will to Cancer Research that suggests that was the disease that claimed Harris. He left a similar amount to a local church and the bulk of his estate to his younger sister. He left his collection of cricket books to the Ealing cricket club, and his tennis books to a journalist friend.

Leave a comment