Bradman to Sehwag : Redefining Great Batsmanship by Defying Tradition (Part 1)

Swaranjeet Singh |

“After being warned for years as to the dangers of playing back on a fast wicket and especially to fast bowling; it came as rather a surprise to see the great Indian batsman transgressing against a principal so firmly fixed in one’s mind.” – Jessop talking of Ranji

“Find out where the ball is. Go there. Hit it.”– Ranji’s three precepts of batsmanship

“There was nothing ferocious or brutal about Spooner’s batting, it was all courtesy and breeding.” – Neville Cardus (legendary writer and a hardcore traditionalist) on R.H. Spooner

At the outset let me clarify two things. Firstly, I am not putting Sehwag in the same bracket as Sir Donald and secondly, I am not moved by the pyrotechnics of Sehwag’s astonishing 293 last week to write this piece. I have been wanting to write about the phenomenon that is Virender Sehwag and this last innings only nudged me to finally put my thoughts into words. That knock was amazing in its ferocity and a stunner particularly when the realization sunk in that he was on the verge of an unprecedented third triple and may well be on course to a quadruple hundred. Yet, the most compelling part of India’s two hundred run opening partnership, for me at least, was the batting of young Murali Vijay. Sadly an ugly sweep brought an end an innings of rare beauty. One hopes we do not have to wait for another wedding in the Gambhir (or Sehwag) household before we see this talented youngster again. His time is now.

But we digress. This is about Sehwag and his batting and most of all it is about what he does to the likes of yours truly, the much-derided traditionalists. He irks us. He turns our long held beliefs on their heads, which makes us very uncomfortable. Eighty years ago an Australian had the same effect on traditionalists and that young man, from the then unknown village of Bowral, provides us the context for understanding Sehwag’s apparent defiance of what we euphemistically call conventional wisdom or tradition.

Traditionalists are very possessive of their turf. Not because they make the laws of the game or coach future generations of cricketers but because they see themselves to be performing a more vital public service. They are the self appointed evaluators of cricketing acumen. They sift the wheat from the chaff, the mediocre from the good and the great. They are the custodians of cricketing greatness. They decide what, besides mere statistics, constitutes a great cricketer. They evaluate using criteria varying from purity of technique (or rather degree of deviation from the orthodox) to the more subjective criteria of aesthetics and attitudes.

Traditionalists have convinced us that purity of technique (more or less settled since around the end of the Golden Age), solidity in defense, perfection in stroke play, correctness of footwork, body positioning etc. were pre-requisite criteria for entering the hallowed halls of the truly great. Add to that the firm conviction that Test cricket was serious business, which required playing each ball on merit, according to match situation and pitch conditions thereby confining the limits for batsmanship by what the bowler, wicket and/or the situation preordained. In other words good batsmanship required respect for your adversary, be it ball, bowler or conditions. Finally there was aesthetics. The fluidity of stroke play of a batsman steeped in the grammar of cricket lent grace, elegance and beauty to the game. The ball in cricket is not hit – it is stroked. Hence the Woolleys, Ranjis and Trumpers personified all that was aesthetically pleasing in batsmanship and essential to be canonized as a great.

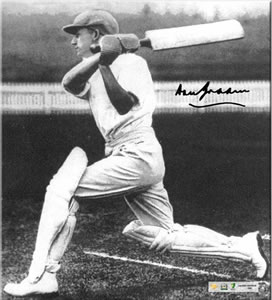

And then came Bradman. . .

Then came the Ashes series of 1928-29 and the 20 year old Donald Bradman. He had a modest start in Tests and did drinks duty in the second Test but came back strongly enough to average 67 per innings in the four Tests he played. Overall against the visiting Englishmen, he scored 925 first class runs that season at 84 per innings. It was a great start by a young man in his first International series but it did not impress the English critics. England had dominated the series, winning 4-1 albeit with consistently diminishing returns. England’s own young prodigy overshadowed Bradman’s figures. Hammond, batting in classical style, had scored an unprecedented 904 runs in his very first Ashes series and was the brightest star on cricket’s firmament not this “most curious mixture of good and bad batting” as Percy Fender, that keenest uf students of the game, called Bradman in his coverage of the tour. Fender was scathing in his criticism. “If practice, experience, and hard work enable him to eradicate the faults and still retain the rest of his ability, he may well become a very great player; and if he does this he will be in the category of the brilliant, if unsound, ones. Promise there is in Bradman. . though watching him does not inspire one with any confidence . . . he makes a mistake, then makes it again and again; he does not correct it or look as if he is trying to do so. He seems to live for the exuberance of the moment. . .”

Unbelievable. No, the traditionalists were not impressed with Bradman.

They found everything wrong with him. His right hand was too dominant, his backlift wasn’t straight, he pulled far too much and, horror of horrors, he pulled even from the stumps deliveries that were almost of good length! He had hardly any defense. No. This wouldn’t do, not against good bowling in seaming and swinging conditions. He would be exposed. They would see him in two years time at home.

The boy wonder, as the 22 year old was called then, kept his appointment and came to England in April 1930 and while the English media was busy writing his epitaph, he scored 236 against Worcestershire in the tour opener. Exactly one month and just seven completed innings later he was at Southampton on the 31st of May, 46 runs short of becoming only the 4th man after Grace, Tom Hayward and Hammond to get 1000 runs in May. Australia lost the toss, Hampshire batted first, were bowled out by mid day and Bradman requested Woodfull to allow him to open the batting to try and reach his milestone. By the time he was finished he was just 9 short of yet another double century.

By the end of the tour he had crossed the two hundred mark six times and the three hundred mark once. His 3000 runs had come at 98.7 per innings. In the Test matches he had innings of 131 at Trent Bridge, 232 at Oval, 254 at Lord’s and 334 at Headingley. He came close to scoring a thousand runs in this his first complete Test series. A record that still stands after eight decades.

The traditionalists who had been scandalized by his obscene disregard for convention were now stunned into disbelief. One wonders what Mr Fender was thinking.

The orthodox in England just could not swallow the fact that Bradman had turned all they had thought they knew about batsmanship on its head. They waited for him to falter and were still waiting twenty years later when he finally called it a day. Those who could not reconcile themselves to his phenomenal success continued to deride him obliquely for not being the batsman on sticky wickets that Hobbs was and this was true. However, what was also true, and what the sharp brain of Bradman realised early, was that he wasn’t likely to face a sticky wicket often enough to change what was otherwise a devastatingly effective batting style. It wasn’t pretty but the scorebook has no columns to record beauty of stroke play. Of what it does record, he scored by the thousands and at a staggering pace.

The fact of the matter is that Bradman’s batting wasn’t radically unorthodox. In fact his Art of Cricket remains, to this day, one of the finest cricket coaching books ever. With exemplary footwork, fantastically early judgment of line and length and exceptional hand eye co-ordination he demonstrated batting the like of which had never been seen before. But he wasn’t orthodox as in orthodox with bold capitals. Yes he had a very dominant right hand grip, which showed even when he drove but he made up it. He hit the ball harder since his grip curtailed his swing particularly in the follow through. He played the ball late as he drove to keep it unerringly on the carpet. His fantastic early judgment and great footwork meant he drove almost everything he could reach from the crease or by jumping out which he did often to lesser pace because of his amazing early judgment of length and great footwork. And yes he pulled almost everything he couldn’t drive but he did it again by fantastic early judgment of line and length and by moving fully back and across – quickly and decisively. Of course, he did not defend much but not because he couldn’t but because he didn’t have to.

And finally, while he appeared to be treating the bowling with utter contempt, this was really an illusion. Bradman never showed anything but the highest professional regard and respect for his peers on the field. Yes his lack of respect for line and length appeared to extend to the reputations of the bowlers that faced him. However, his apparent arrogance is better understood as the supreme self-confidence of an athlete of rare ability who was also blessed with uncommon physical and mental faculties.

The traditionalists in England refused to understand the Bradman phenomenon but today when Bradman and all his critics are gone, no one talks of his unorthodox grip anymore or his lack of respect for line or lineage. All that remains is the unanimous consensus that he was far and above the greatest batsman that ever was.

Bradman’s example did not lead to a revolution in the sense that the world has yet to see another like him. But that’s not surprising. Too many attributes of natural talent, finely honed skills, mental and physical strength were combined in this supreme athlete and it will take nature much longer than just eight decades to duplicate the mould. Nevertheless, the fact that Bradman was a one off phenomenon meant that we continued to define great batsmanship in classical terms.

Some things, however, did change with Bradman.

The world understood, over time, that while changing conditions may not alter the fundamentals of the game, the basics could be adopted and harnessed by talented individuals to obtain the best results under varying conditions. As conditions continue to change over time and vary greatly from one country to another cricketers need to be adaptive enough to add to the vocabulary of batsmanship even while remaining largely true to its basic grammar.

Test batsmen have always played percentage cricket, selecting shots that were least likely to bring about their demise. They still do that but the percentages are not always the same. With increasingly batsman friendly conditions the risks and risk-assessment by batsmen has changed. On the hard true surfaces of West Indies, batsmen started playing a brand of cricket that made the Caribbean and entertainment synonyms. The dead sub-continental wickets made for wristy stroke play that is uniquely South Asian. The Australians, batting mostly on truer though still somewhat sporting wicket, played with great all-round aggression. Those from England continued to fall between the two stools of traditional orthodoxy and the aggression that seemed to be lacking only amongst them of all the major cricketing nations.

In our hall of cricketing greats, where we had reluctantly allowed Bradman to join Grace, Trumper, Ranji, Hobbs and Hammond, we continued to restrict membership to those who fitted our rigidly orthodox criteria. Thus the Huttons, Worrells, Soberses, Chappells, Gavaskars and Pollocks received wide acceptance with batting built around a basically orthodox technique. But the batsmen, barring the openers showed increasing belligerence at the crease. Barry Richards made the first crack in that mould too. Overall, however, Test batsmen continued to respect the line of the ball and the lineage of the bowler.

Vivian Richards in the 1980’s and Sachin Tendulkar in the 1990’s changed that to offer the world a glimpse of what Bradman had once done. Like him, these masters remained, at their core, technically close to the basics. Their feet moved close to the ball, their heads remained still and the bodies perfectly balanced and above all their stroke play, despite the latent and surface aggression, remained a thing of beauty. Where they followed Bradman’s example was in realising that the percentage had been redefined beyond mere covering of the wickets and the risks for more aggressive stroke play were minimal. Most importantly, they were Bradman like in their irreverence of the opposition. Tendulkar (at his peak) and Richards showed no respect for reputations and their attitudes, even more than their batting styles, made a mockery of the most defensive field placements put in place to curb their stroke play.

They are universally accepted and celebrated as modern day greats. We were willing to condone hitting the ball from outside the off stump to midwicket and stepping back to cut from the leg stump past point. To that extent we had already redefined great Test batsmanship for good but were not prepared to grant more concessions to unorthodoxy.

And then came Virender Sehwag. . .

Very good article, and thought provoking.

Comment by silentstriker | 12:00am GMT 13 December 2009

Great article so far. Enjoyable reading as you’re laying out your case. If I’m picking up where you’re going correctly, the emergence of Hayden and Gilchrist at near the same juncture as Sehwag is not to be viewed as coincidence.

Comment by Matt79 | 12:00am GMT 13 December 2009

nice article …. looking forward to reading part 2

Comment by ret | 12:00am GMT 13 December 2009

Very interesting some of the comments made about Bradman by contemporary critics….you could use them verbatim for Sehwag. Bradman seemed to be record concious which Sehwag is not. Maybe this is something he should now do?

Comment by bode | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

Hi SJS, excellent article. But I think Lara from the modern batting greats would be a much better example to your point than Sachin. Sachin is perhaps the closest to technical perfection among the modern greats, AFAIC. 🙂

Comment by honestbharani | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

Looking forward to part 2, excellent article so far.

Comment by GingerFurball | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

Traditionalist in the house!!!

Well written SJS. Some things i agree with but i disagree with alot of stuff TBH. I shall bring my complaints to you in a few days…

Comment by aussie | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

Very good as usual SJS – some thought provoing stuff there.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

There’s some interesting analogies in there SJS…..thanks well written

Comment by JBMAC | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

“He plays the ball on merit (the Sehwag definition of merit mind you) and plays it accordingly, hits it between fielders and so on.”

This part could maybe have been expanded on, it’s perhaps the thing I love most about Sehwag’s approach to batting.

Comment by GingerFurball | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

I had warned that there is going to be some controversial stuff here so I am not surprised. Look forward to the “complaints”. Will try to answer.

Comment by SJS | 12:00am GMT 14 December 2009

No offence, SJS.. I agree about Lara’s footwork and that Sachin is not as good in that. But I was talking about the backlift and that arc that is created and Lara’s jumping around during the initial part.. Far more prone to danger than Sachin’s technique, IMHO. But yeah, I agree that was not the point. I was juz referring it mostly in jest.. Hence the smiley..

The article is wonderful though.. I seriously didn’t have any idea that Bradman was ridiculed for his technique so much back then. Even in the books you had sent me, they refer to him in a pretty reverential tone.. So hard to imagine him, of all people, copping it so much. I mean, I have heard that people commented his technique was not perfect, but never thought it was to such an extent.

And I agree completely about Sehwag.. The main thing is his aggressive intent. He thinks of defending a ball ONLY when he cannot hit an attacking shot to it. There are so many around the world, including some all timers like Sachin and Ponting, who resort to defence first and then attack… I mean, you can say he is premeditated in his attacking intent but that is just as true for an Atherton or Boycott or Gavaskar who were premeditated in their defensive intent. And we don’t criticize them for that, do we? Even Ponting and Tendulkar tend to be pre meditated in defence so many times.. And so was Lara when he was around. We never hold that against them.. Why hold this against Sehwag?

Comment by honestbharani | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

Excellent, throught provoking stuff SJS, both articles. Very well done.

Comment by silentstriker | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“No offence, SJS..”

No offence taken HB 🙂

Just to clarify that Lara Sachin point. Its not about being technically stronger or deficient. Both have wonderful techniques. I was talking about deviation from the classical orthodoxy. That’s all. So starting with grip, stance, backlift the classically orthodox has its confines of footwork, body positioning etc. The top hand is the dominant hand, the body for most part is side on, head is over the ball, toes and shoulders are pointing roughly in the direction of the shot and so on.

Sachin deviates more in this than Lara. Tha’s all. Its no big deal really because the basic technique remains solid but it is noticeable and will also affect some of your play. To take just one example, Sachin’s swing is restricted by his right hand dominated grip so in his atempt to keep the bat from closing, he will control the end of the swing and hold the bat blade about horizontal at the end of his drive.

Lara on the other hand is able to swing his bat the in a much bigger arc and the bat’s end will end up facing the sky. Being the great players that they are/were, they both get great results its just that Lara’s is a bit more natural and unrestrained whereas Sachin’s is cultivated and controlled

Finally there is Sobers whose grip is completely devoid of any influence (in the power he generates) from the bottom hand. So he ends up with the bat going on to almost hit him on the back !

One could go to the other extreme to someone like Bradman whose right hand is so dominant that his swing terminates before his hands reach his chest level Bradman, however, does not bother to control the swing, allows his wrists to naturally fold at his wrists and uses his great hands and fractionally late driving to keep the ball on the ground.

Now these four are on everyone’s shortlist of the greatest batsmen of all time yet they cover a spectrum of grips from most orthodox Sobers , through, Lara onto Sachin and then Bradman.

It would be silly to say that any of them were technically deficient but its easy to see how they vary from the classical.

Thats all there is to it.

Unfortunately, the traditionalists can tend to be a bit fanatical and miss the overall package for the specific details which is sad because if every player on the planet played in exactly the same manner, even if it was perfectly correct, the game would lose most of its charm. 🙂

Comment by SJS | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

In the end, people have to understand: technique is a means to an end. It is not the end itself. Once people accept this they’ll enjoy all kinds of batsmen rather than get into tedious arguments about how x would do in y era.

Comment by Ikki | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

That second part is truly excellent and the best cricket article I have read in a while. My understanding of the technical aspects of the game is limited and I too have been rather mystified by Sehwag’s success even while enjoying his innings. The article went a long way in educating me.

Comment by Dissector | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

One of the best threads on the forum.

Comment by G.I.Joe | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

I honestly don’t feel Sehwag is all that special a player. Yes, he has excellent eye co-ordination (no better than a pieterson or Gilchrist however) a very aggressive approach and an excellent ability to keep going.

But the more modern cricket i watch, the less i feel we can judge a batsmans quality on totally flat tracks. It doesn’t take bravery to attack Kulasekara or Matthews on this sort of pitch. Sorry. If anythings redefining batsmanship its the pitches and equipment.

Comment by Irish_Opener | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

Learn something new everyday I guess. Never knew Bradman had a lot of critics against his technique.

Comment by metallics2006 | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“In the end, people have to understand: technique is a means to an end. It is not the end itself. Once people accept this they’ll enjoy all kinds of batsmen rather than get into tedious arguments about how x would do in y era.”

Yeah, this is how I feel.

Comment by Uppercut | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“In the end, people have to understand: technique is a means to an end. It is not the end itself. “

So how would you two feel lets say in the upcoming next decade. We have a potential revival in quality pace attacks in AUS (Hilfenhaus/Siddle/Johnson) – WI (Taylor/Roach/Edwards) – SA (Steyn/M Morkel/Parnell) IND (Sharma/Sreesanth) – PAK (Asif/Aamer/Gul) – SRI (Malinga/Prasad/Thushara).

Along with potential decrease in flat decks (although it may still remain if the ICC doesn’t do some restrcuting & actually do something about pitches worldwide) & the balance between bat & ball becomes a bit more even. Would you still look back at the last 10 years of batsmen with the same high regard?

Comment by aussie | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

They scored bucketloads of runs, more runs than anyone else did. What the hell else were they supposed to do?

Comment by Uppercut | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“They scored bucketloads of runs, more runs than anyone else did. What the hell else were they supposed to do?”

Ha the ideologies are definately coming out now..

Why did they score a bucketloads or runs more than their contemporaries?. Isn’t it obvious the decline on quality pace attacks (outside of AUS) for this decade & increase in flat decks in the main reason for this?.

If you agree with the above then surely if pace bowling standards get better worldwide (along with better pitch standards) in next decade & a more even battle between bat & ball returns & averaging 50 is something [B]only[/B] the upper echelon of batsmen can acomplish – rather than almost everyone who hits a purple patch.

Then surely you can’t rate FTBs of this era in the same breath as the potential future dominant batsmen who would play in a era/period where they will also score runs than their contemporaries also – but rather under more difficult batting conditons – rather than on roads.

Comment by aussie | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

” Would you still look back at the last 10 years of batsmen with the same high regard?”

People look back at the batsmen of the 1930s with fondness and high regard, don’t see why this generation will be any different.

Comment by GingerFurball | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“People look back at the batsmen of the 1930s with fondness and high regard, don’t see why this generation will be any different.”

Really?. Last i checked the 1930s, 20s & post WW1 batsmen (except Bradman, Hammod & Headley also maybe McCabe) have more issues surrounding them vs batsmen of this 2000s era.

Since the pitches where probably flatter & no real quality fast bowlers/fast-bowling combo existed then except for Larwood/Voce & Gregory/McDonald, which is worst than this decade.

Comment by aussie | 12:00am GMT 15 December 2009

“Why did they score a bucketloads of runs more than their contemporaries?. Isn’t it obvious the decline on quality pace attacks (outside of AUS) for this decade & increase in flat decks in the main reason for this?. “

Listen, it’s very simple; if those that were supposedly better score less runs than those that are supposedly worse, then you can no longer devalue those runs.

Not every innings is the same, there are more difficult innings and easier ones. Don’t let me fool you into thinking I think all performances are equal.

However, over 10 years, the fact that someone like Tendulkar, without minnows, is averaging 47 and his teammate (Sehwag) is averaging in the 50s, says it all about supposed easiness to score runs.

There is no “he cashes in on flat-tracks more than others”, because flat tracks are found easier for everybody not just a select few.

Comment by Ikki | 12:00am GMT 16 December 2009

I remember doing an analysis sometime back abt Sehwag in games involving him with Dravid and him with Tendulkar …. At that point (iirc) he beat both Dravid and Tendulkar to 5000 runs (which is quite an achievement considering how good Ten and Dravid are)

Comment by ret | 12:00am GMT 16 December 2009

sachin should make 15500 to 16000 test runs to stop mcgrath to say that ricky will overcome him.. haha.. in 190 tests sachin should go past 15600 runs playing till jan 2012 atleast to stop ricky to think about surpassing him (try to score 16000 test runs)

Comment by Anirban | 12:00am GMT 2 January 2011