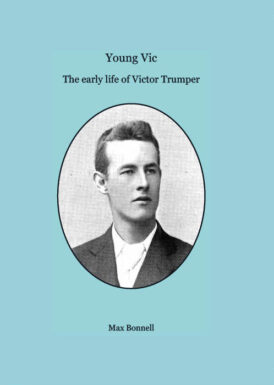

Young Vic

Peter Lloyd |Published: 2025

Pages: 98

Author: Bonnell, Max

Publisher: Red Rose Books

Rating: 5 stars

Later this week Max Bonnell’s look at the early life of Victor Trumper is published. Having been fortunate enough to have been provided with an advance copy of the text I was able to review the book three weeks ago here.

Those who have not read my review, or those who did so promptly, will probably not have seen Max’s comment:-

Thank you for a most generous review. I do hope you’re wrong, though. I know at least one writer is about to attempt a detailed biography (I’ll leave it to him to announce it when he’s ready) and I do hope he finds something that eluded me – that’s how history advances. I believe I found one potentially important document that no previous researcher has uncovered, so who’s to say there isn’t more?

Someone else who has been able to read Young Vic pre-publication is Peter Lloyd who, after his impeccably researched biographies of Warren Bardsley, Monty Noble and Charlie Macartney is, if there is more to be found, the man I would back to make the discovery.

Peter has kindly agreed to let us have his thoughts on Young Vic, and I do hope that his closing sentence means that he is the writer Max is referring to. If he is then Max’s optimism may well prove prescient.

In the Summer 2024-25 issue of 1876, the annual magazine for members of the Sydney Cricket Ground, Gideon Haigh wrote, yet again, about his reasons for not undertaking a “conventional biography” of Victor Trumper[1]:

I…experienced misgivings. Three previous biographers [Jack Fingleton in 1978, and Peter Sharpham and Ashley Mallett both in 1985] had struggled to make much of [Vic]. The primary material was thin, his period remote, his contemporaries long gone, and the mythology thick indeed.

Haigh contended that legend is an uneasy companion of biography, if not an outright enemy. His compromise (a bargain struck with the past) was to focus largely on Trumper lore. To this end, he argued persuasively that an iconic, increasingly pervasive, image of the beau ideal has helped to consolidate and extend Victor’s stature as a combination of peerless cricketer and modest man. While Trumper’s timeless reputation was thereby enhanced, others, many of whom had superior records to the Australian’s first-class career statistics, and who possessed both sublime sporting talent and indomitable spirit, suffered from a naturally progressive diminution of their glory day brilliance. What they were lacking was the lustre of an aesthetic signature. Such an appealing perspective.

This recent nostalgia 1876 essay concluded with the explicit suggestion that George Beldam’s 1905 action photograph of Trumper ‘Stepping Out’ prevented his subject from becoming no more than a distant name with a fading echo, a statistical remnant buried deep beneath a century’s further achievement. Haigh doubts wherever an older version of himself would have appreciated the long since departed cricketer’s credentials, had he not been exposed as a youngster to such a photograph resonant of the gaiety and gallantry of unorthodox batsmanship.[2] Bold as this statement is, it rings hollow. However, that’s not the focus of this review, rather more of a preface to the main story. Perhaps for the efforts of a future biographer but still, nevertheless, pertinent to what follows.

Well credentialed Australian cricket historian and prolific author, Max Bonnell, has taken the bit between the teeth and tested the depth of Victor Trumper’s immortality. In an engaging new publication, Young Vic: The Early Life of Victor Trumper[3], to be published in March 2025, Bonnell looks beyond what has gone before and asks whether there’s any genuine opportunity to advance our appreciation of the roots of Trumper’s artistry and talent – his “genius”. In so doing, he suggests an avenue of historic enquiry that has lain largely dormant for well over a century.

Bonnell concurs with Haigh regarding previous efforts to explore, at least the early decades, of Trumper’s life, describing them as “imperfect” investigations. He strives, in his forensically clinical way, to examine how an illegitimate child, born into hardship, with no cricket in his family and no material advantages, became the most memorable cricketer of his generation. With the rationale for the book explicit upfront, Bonnell’s focus remains true to purpose throughout. In hindsight, however, he may have considered modifying his depiction of intent to include just Australian-based players. While Trumper’s unique credentials were heralded widely throughout the cricketing globe, his batting talents were far from universally acclaimed in the ‘Motherland’ after two lacklustre Ashes tours, with several English heroes of the first decade of the 20th Century held in higher esteem. A minor issue but one warranting consideration.

The author is at his best when discussing Trumper’s ancestry. He begins by dispensing with the historically thorny issue of illegitimacy, a matter which had proved, under advisement, an unnecessary confounder, a bridge too far, for biographers Fingleton and Mallett. In the 1870s and beyond in colonial Australia, as in the Motherland, bastardry was still a blight on the character of all concerned – parents and children alike. So it remained for some, or so it seemed, a century later.

Distancing himself from such concerns, Bonnell argues persuasively, and for a range of reasons, as to why Charles Trumper and his wife Louisa (née Coghlan) are unlikely both to be Victor’s biological parents. He speculates then that there is some possibility that Louisa may be his mother. Exploring all ancestral research avenues, Bonnell admits to coming up with blanks. No birth certificate for Victor has been found. Nor is it ever likely to materialise. Adoption records are non existent, such documentation not being required until well into the second decade of the 20th Century when the process was legally formalised in New South Wales. The unfortunate loss by fire of the 1881 New South Wales household census forms was a likely calamitous blow for any would-be future biographer as it may have provided evidence of Victor’s place of residence when he was a mere toddler.

Bonnell asks all the pertinent questions, circles around the tiny handful of inconclusive facts (including the tantalising prospect that Trumper was born a year later than commonly believed) and concludes that there’s only the most minuscule chance of the question [of who Victor’s biological parents were ] being answered a century and a half later. As a lawyer, Bonnell is well positioned to advise that circumstantial evidence and guesswork are often uncomfortable bedfellows.

Ultimately, he concludes that, regardless of the “true nature” of the biological connection between Charles and Victor, the former carried out his fatherly duties in a caring and diligent fashion. Presumably, while not being explicit about Louisa’s maternal instincts, he assigns her much the same loving parental qualities.

Beyond the matter of the subject’s birth, Bonnell handles all the regular family parameters with aplomb. United Kingdom ancestry, migration to and from Australia and New Zealand, marriages, births and deaths of siblings and others, and the sites of various family abodes in the inner Sydney suburbs during the period under review (broadly 1870-1900) are noted in a fashion far clearer than in the past. Added to which, specific sources of information are provided as endnotes. A small quibble with the extensive referencing from newspapers and the like. Page numbers of cited issues of broadsheets, tabloids, magazines and gazettes are not provided. For devotees driven to agonise over all materials this is more than a minor issue, one that could have been remedied by a mere click of the mouse.

A matter of far greater consequence and perhaps the weakest (we are keen to suggest ‘least informative’ because, truly, the book is a superior product overall) element of Young Vic is the paucity of attention which Bonnell gives to poverty as an endemic feature of the Trumper domestic, community and commercial world. This lacuna is far from an unknown circumstance as the author himself acknowledges from the outset. Bonnell’s most explicit commentary about the pervasiveness of poverty in inner Sydney during the mid to late 19th Century is contained within two brief, albeit graphic, paragraphs:

For at least three generations, the Trumper family was stalked by premature death. Like most working-class people, they lived in cramped houses in inner-city suburbs, served by only the most primitive sanitation. Contagious bacteria thrived in these environments, where it could be hazardous simply to breath the air or drink the water.

And:

Surry Hills was not a comfortable neighbourhood. There’s a whole sub-genre of Australian fiction about the hardship of growing up poor in Surry Hills. Its small, dingy terrace houses were jammed up against factories and workshops in narrow, pungent streets. Drainage was inadequate, poverty endemic and crime was common…[4]

Bonnell is onto something important here but baulks at consolidating his argument. Any number of selected passages from the fine body of Australian fiction that flags the desperate straits within which Australian middle- and lower-class urban dwellers toiled throughout the second half of the 19th Century and beyond, would have enlivened and coloured his account. Writers of the calibre of Ruth Park, Kylie Tennant, Lewis Rodd, Henry Lawson, Louis Stone, Christina Stead and, more recently, Helen Garner, among others, are all sensitive observers of the squalor of life in the Sydney slums, and, importantly, of the human capacity to ‘make do’ by various organisational, familial and personal means even without access to state welfare or religious and benevolent charity systems. In his short account, Bonnell has, perhaps through necessity, foregone an opportunity to provide an additional layer of insight by blending the heightened allure of fiction, with its capacity to allow the poor to speak for themselves, with his more prosaic narrative.

The essence of Bonnell’s treatise is that, somehow, Victor Trumper, despite growing up in an environment of extreme vulnerability (notwithstanding that his father/elder male in the household was gainfully employed throughout the entirety of his youth), was able to survive, and indeed, thrive in his chosen field without any significant cricketing heritage.

The explanation of this phenomenon is disappointingly thin. Fundamentally, Bonnell’s account fails to address the structural causes of poverty in New South Wales for the entirety of the period under review. As Anne O’Brien, now Emeritus Professor of History at the University of New South Wales, wrote in the foreword to her seminal 1988 graphic portrayal of the extent of destitution in the “working man’s paradise”, Poverty’s Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880-1918[5]:

As the central economic unit, the family was very vulnerable: to fluctuations in the macroeconomy, to environmental pressures such as poor housing and serious illness, and to a patriarchal ordering of social relationships. It was also vulnerable to having too many dependent members at any one time, as well as to sheer bad luck. In analysing structural causes of poverty [my] book uncovers destitution in a land of plenty.

Several disciplinary branches of Australian historical scholarship provide an impressively detailed and compelling theoretical body of work which describes and explains the grim realities of the final quarter of 19th Century urban life for the working classes.[6] Researchers include those with a focus on urban studies, social geography, social collectives, economic history, labour politics and the working classes, poverty, feminist history, transport and the family. Some names that spring readily to mind include Jenny Lee, Shirley Fitzgerald, Max Solling, Christopher Keating, Brett Lennon, Garry Wotherspoon, Max Kelly, Eric Fry, Michael Gilding, Jill Roe and Robin Walker. And the list goes on.

It would have been useful for Bonnell to allude to the work of at least some of these diligent researchers and capable authors in contextualising the circumstances of Victor Trumper’s prodigious early cricketing stature in an otherwise unremarkable (for the times) upbringing. Two examples, below, suffice to suggest how such inclusions may have enhanced his account.

First, given that the author focuses on Charles Trumper’s long career as a Sydney boot maker, “boot-clicker” or “clicker”, it seems appropriate to explore the extent to which pedestrianism remained the major form of transportation even in the last quarter of the 19th Century. A two or three mile walk to and from work at the factory or docks or building block was considered unexceptionable for the time. Horses were expensive to buy and fares for horse-drawn carriages were steep. A system of tramways (first steam and later electric) was established in Sydney between 1880 and 1884 as the city expanded to the west and, to a lesser extent, the south. However, the price of a trip from an inner suburb to the heart of the city was an initially prohibitive 3d.[7]

As a corollary, knowledge about the number of tradesmen (skilled and unskilled) working in the shoe industry during this period and where they were located would be valuable. How competitive a trade was it and how cut-throat did manufacturing and retailing become as a consequence of changes in technology? What impact did mechanisation have on full time employment and on part-time and casual labour? And what was the typical wage of a factory employee? This is but one example of how contextualising a major commercial activity might enhance our appreciation of individual circumstances. So important if a family’s well-being was dependent on the breadwinner (overwhelming the father) mastering a trade and thereby ensuring his viability as a provider.[8]

Shirley Fitzgerald (née Fisher), for many years the City of Sydney’s Historian, with overall responsibility for the collecting, cataloguing and displaying of the City Council’s historic archive, undertook a review of the urban workforce by occupational groups in the 1980s. Boot and shoemakers figure prominently in her oft quoted classic study Rising Damp.[9] She describes how mechanisation of the boot industry saw a proliferation of factories in Sydney with a concomitant deskilling at the individual level but increased output per worker[10]:

The total output of boots and shoes for Sydney in 1870 was estimated to be about 15,000 a week. The industry was strongly located in the city, and the suburbs of Redfern and Waterloo immediately south of the city. Factories employed more hands, rather than proliferating. For the colony as a whole, the number of boot factories had been reduced over the twenty-year period, while employment doubled. In eight New South Wales factories over 100 hands were employed in 1891, with one factory employing 290.

The wages paid varied according to skill, age (school-age boys and girls were often employed for a pittance) and gender, with male clickers, considered to be among the more expert and paid accordingly, earning perhaps as much as £2/10s a week in return for working 10-hour days “all year round”, as Bonnell notes from a column in the Sydney Morning Herald.[11]

From another column in the same issue of the Herald, we learn that the overall Sydney labour market was tight with general labourers of all classes walking about in large numbers unable to procure work. However, the boot and shoe trade was less affected by the depression than other branches of industry, notwithstanding the fact that there was a slackness of work” and [boot and shoe men were also] walking about. In a quintessential Australian way, coopers were considered to be the only tradesmen enjoying anything like brisk times![12]

Charles’s bold decision, as described by Bonnell, to leave steady employment, which provided a reasonable wage, to establish his own shoemaking business (in partnership with Arthur Brown who likely provided the requisite financial capital) was full of risk. He likely realised that a fixed salary would always be insufficient to extricate his growing brood from strapped circumstances. He knew too that, in the mid to late 19th Century, people (more often than not women) tended to shop locally with Sydney already splintering into distinct socio-economic groups based on class divisions.[13]

To this end it seems probable that Trumper and Brown marketed the wares of JW Ward Bootmaker in ways that promoted their standing within the local community. As Max Solling noted in his social history of the nearby suburb of Glebe, and which has relevance throughout the inner city, retailers and their wholesale suppliers, needed to rely on the continuous patronage of a relatively small but fairly concentrated clientele.[14]

The pair’s prospects of commercial success would have been heavily dependent on their capacity to restrain manufacturing and labour expenses while maximising profits. Charles’s lengthy union affiliations (Bonnell points out that he was elected President of the Sydney branch of the Boot Trade Union in 1892) would seemingly have meant that he and Brown paid their employees wages at least the equivalent of their competitors. The business was successful enough over the course of the next several years for Charles to be able to relocate his family from a small Surry Hills rented tenement to a larger house in the more salubrious adjacent suburb of Paddington in 1896, and a short while later to an even airier terrace house in the same suburb. While still a tenant, he would by then have been optimistic of future prospects, perhaps even contemplating land and house ownership.[15]

Extrapolating from known details, Bonnell fills in as much of this period of the Charles Trumper family saga as he can through assiduous research and careful assessment of motivation. His scholarship here is impressive. What he may usefully have added was that Charles possessed an exceptional degree of spirit and grit that helped him confront significant adversity and challenges. Qualities that could be witnessed by members of his close family circle and, perhaps, emulated and channelled into their own areas of endeavour. As an adult, Victor was an astute observer of life and behaviour, far more so than has been traditionally alleged and retold ad infinitum. In his formative years, the young man would have been fully aware of Charles’s determination to improve his, and his family’s, circumstances. And he would have admired his father’s doggedness to succeed.

A key component of Bonnell’s treatise is attempting to explain the improbable. How did Victor Trumper’s ascendancy to cricketing grandeur occur given his socially humble beginnings? The overview of the early stages of Victor’s career from eagerness to participate as a youngster in regular morning practice on the green, open spaces around Moore Park, through his Fort Street Superior High School match performances and his emergence as a club and then representative cricketer of rare talent is well depicted. As is the sense of growing pride shown by his father as the teenager matures towards manhood. Yet there is a missing contextual feature of the late colonial New South Wales era which, with due consideration, has the potential to shine some light on the question as to how the young boy’s nascent talent at cricket expanded exponentially in an apparent familial sporting vacuum. This missing factor is the increasingly significant concept of contested sport, and recreational physical exercise more broadly, as an important element of popular culture.

In the last quarter of the 19th Century the colonial working and wage earning classes in the inner, factory-dense, suburbs of Australian cities, and in some of the larger country towns, were defined by their patterns of housing, work and consumption.[16] However, as Richard Waterhouse, among others, contends, they would also come to be distinguished, at a period when the luxury of leisure time was becoming more widespread, by recreational activities which were closely tied to their community identity and status.[17] As part of this process, particular aspirational values and competitive attitudes were attached to participating in contested games or watching others play. Qualities such as setting goals, undertaking hard work, and testing oneself through personal risk and sacrifice, were becoming important features within the social and cultural milieu among the working-classes of colonial society.

Concurrently, there were also emerging ideas about club allegiances and neighbourhood affiliations, group co-operation, inclusiveness, and ethics of care between participants. Much of the essence of cricket, and of the game’s hallowed laws appear, at least superficially, to be wholly amenable to such ideals and beliefs. The momentum of this dynamic cultural force was burgeoning in New South Wales just as Victor Trumper, with a free-spirited mindset and with firm personal motivations, was just getting into his stride. His determination to succeed at his chosen sport was deeply rooted while he was still living at home with his parents and siblings.

In this review two possible avenues for further development of Bonnell’s Young Vic, have been presented. There are other features of Trumper’s early days that could be expanded profitably. For example, more could be made of his school boy experiences. Charles Rodd’s personal account of his schooling at Fort Street in the first decade of the 20th Century in his A Gentle Shipwreck, an engrossing social history of the era, before and during the First World War[18], is a goldmine of intimate details which night add substance to what are generally known bare-boned, generic facts of Trumper’s years at the same school.

Notwithstanding these suggestions, this reviewer has nothing but praise for Bonnell’s excellent crystallisation of the known circumstances of the formative years of Victor Trumper and for the additional details that he’s uncovered which add immeasurably to the information base about the cricketer’s early life. Although the author suggests that all that happened after Vic’s selection for the 1899 Ashes Tour of England is already known, and that as a consequence a biography is unnecessary, it seems there remains an opening for a diligent biographer to test that assertion.

[1] Haigh, G. “A Thousand Words”, 1876, Summer 2024-25, pp. 28-31

[2] Haigh, G. (2009) “Top Shot That”, Portrait 34, National Portrait Gallery. See: https://www.portrait.gov.au/magazines/34/top-shot-that

[3] Bonnell, M. (2025) Young Vic: The Early Life of Victor Trumper, Red Rose Books, Reading, United Kingdom. See: https://redrosecricketbooks.com/

[4] The population of Surry Hills in 1871 was around 15,000, doubling over the next twenty years. While housing stock (of poor quality) was increasing apace, overcrowding was becoming a significant problem, with “five or six people occupying a two- or three-room house”. See: M. Kelly (ed) (1978) Nineteenth Century Sydney, University of Sydney Press, Sydney, p. 71

[5] O’Brien, A. (1988), Poverty’s Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880-1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, p. 2

[6] Jenny Lee and Charles Fahey provide an excellent summation of the reasons why the working classes in Australian cities did not share in the fruits of the periods of national economic boom between the early 1860s and about 1891. See: Lee, J and Fahey, C. (1986) “A Boom for Whom? Some Developments in the Australian Market, 1870-1891”, Labour History, Number 50, pp. 1-27

[7] Wilson, R.et al (1970) The Red Lines: The Tramway System of the Western Suburbs of Sydney, Australian Electric Traction Association, Sydney, p. 7

[8] Fisher, S. (1985) “The family and the Sydney economy in the late nineteenth century” in P Grimshaw et al (eds) Families in Colonial Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 153-62

[9] Fitzgerald, S. (1987) Rising Damp: Sydney 1870-90, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp. 147-50

[10] ibid, p.149

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 March 1880, p. 7. Fitzgerald reports 48 shillings a week for a male clicker and 23 shillings for a female doing the same work.

[12] ibid

[13] Fitzgerald, S. (1987), op cit, p. 227

[14] Solling, M. (2007) Grandeur and Grit: A History of Glebe, Halstead Press, Sydney, p. 109

[15] See RV Jackson (1970), “Owner-Occupation of Houses in Sydney, 1871-1891, Australian Economic History Review: Urbanization in Australia, Volume X, No 2, pp. 138-54 for an account of the percentage of tenanted and owner-occupied private dwellings by Sydney suburb. The percentage of tenanted dwellings in Surry Hills in 1891 was 86 of 4,513 houses; and 77 percent in Paddington of 3,141 houses.

[16] Solling, M. (2007), op cit, p. 181

[17] Waterhouse, R. (1995) Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman, Sydney, pp. 112-14. See also Waterhouse, R. (1908) “Culture and Customs”, Dictionary of Sydney at https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/culture_and_customs

[18] Rodd, LC (1975) A Gentle Shipwreck, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne

I have to say that I find this continued, and seemingly obsessive, interest in Victor Tumper misplacd. Especially when there’s virtually nothing new to discover by way of dcuments, and crtainly no unexpected discovery of video action on the Test field when batting. Surely, the researchers and interpreters’ time could be spent in far more rewarding ways – to themselves, as well as to other cricket enthusiasts – than this morass of gloating and further homage. I suspect that Trumper himself woud be acutely embarrassed by it all!

Comment by PETER BARRINGTON KETTLE | 8:36am GMT 10 March 2025

COMMENTS ON PETER LLOYD’S REVIEW OF THE BOOK TITLED

YOUNG VIC: THE EARLY LIFE OF VICTOR TRUMPER (2025)

Although I have a keen interest in Australian history of Victorian times, I know about very few of the leading cricket players of that era. But one exception is Victor Trumper, as a couple of years ago a friend lent me Peter Lloyd and Peter Schofield’s impressive tour through Victor Trumper’s times and his cricket career. I found the two Peters offering absorbing as well as being visually stimulating with its showcases of interesting memorabilia. My appetite whetted, I’ve since found out quite a bit more about this extraordinary player, looking over some of the papers presented ten years ago at the seminar held in Sydney on the centenary of his death.

Peter Lloyd seems to have gone – how shall I put it – overboard in his lengthy review of the Young Vic book, running as it does – after his “preface” is finished – to a touch over 3,000 words, covering four and a half pages of A4 paper (without including his eighteen End Notes). Not that length itself should be a stumbling block as it took me no more than around forty minutes to peruse it.

I have subsequently gone back over Peter Lloyd’s review in order to produce these comments. Reflection on it all, I have found it difficult to decide whether his two main suggestions – both discursively unfurled – for an elaboration of Max Bonnell’s 98 page book is a genuine attempt to be constructively helpful; or whether his lengthy review is essentially a vehicle to display his scholarly grasp of the socio-economic circumstances of the mass of people living during the time of Victor Trumper’s upbringing? I’m still not sure, either way, though there are a number of places where his review seems to self-contradictory and at other times prone to nebulous statements. Let me give a few examples to hopefully forestall readers of my comments thinking me over-critical or harsh.

Taking Peter Lloyd’s first suggestion, of adding a fleshed out context for Trumper’s upbringing by focussing on the pervasive hardship and poverty of Sydneyites in the late-19th century, including the squalor of its residential slums. He chides Max Bonnell for “the paucity of attention” which is given to this feature (“two brief paragraphs”), saying that he has “foregone an opportunity to provide an additional layer of insight by blending the heightened allure of fiction {meaning novels} – with its capacity to allow the poor to speak for themselves – with his more prosaic narrative.”

Yet immediately after this, Peter Lloyd alludes to the fact that the grinding hardship and poverty which characterised the generality of Sydney’s residents – especially those of the inner areas in which the Trumper family lived when Victor was growing up – didn’t actually apply to his own parents, nor to his relatives it seems! So wouldn’t it have been better to have a few paragraphs saying just that, incorporating the reference he makes to Trumper’s father – Charles – being “gainfully employed throughout the entirety of his {Victor’s} youth”. Later on, noting Charles’ enterprise, and boldness, in setting up his own, commercially successful, shoemaking business during the relevant period, 1870-1900.

“The business was successful enough over the course of the next several years for Charles to be able to relocate his family from a small Surry Hills rented tenement to a larger house in the more salubrious adjacent suburb of Paddington in 1896, and a short while later to an even airier terrace house in the same suburb.”

Peter Lloyd’s second suggestion is to have the question more fully addressed of how it was that Trumper had a zest for cricket, and flowered at this sport, when there was no background of cricket in his family. “Victor Trumper, despite growing up in an environment of extreme vulnerability, was able to survive and, indeed, thrive in his chosen field without any significant cricketing heritage.” (The term vulnerability, he indicates soon afterwards, is used to refer primarily to the risk of bad luck and falling out of work or falling seriously ill from the primitive sanitation that typified most of Sydney’s inner city housing during the late-nineteenth century.)

At this point, Peter Lloyd puts the boot in, saying: “The explanation of this phenomenon is disappointingly thin”. Whilst inherited interest and skill is, I gather, common among sports stars, the absence of these features is by no means rare. And so one should not be all that surprised of their absence in the case of Victor Trumper. To take just a few other examples: Mike Tyson’s parents and relatives were not known for their boxing ability, and this applied also to Muhammad Ali. Nor did Gary Player’s parents play golf. And Bjorn Borg’s parents were no good at tennis (though his father was highly competent at table tennis). So I don’t think the puzzle that Peter Lloyd feels he is confronted with needs an in-depth or special explanation.

From a short piece by Gideon Haigh, produced in November 2009, I learned that (to quote him) “Trumper was tutored as a junior by Charles Bannerman, Test cricket’s first centurion {making 165 not out, on debut}, but proved uncoachable. Writing of Victor Trumper’s youth in early-1913, SH Bowden recalled Bannerman’s unheeded entreaties (‘Leave it alone, Vic; that wasn’t a ball to go at’) and his eventual decision to let the boy do as he pleased. The characteristic lasted. Monty Noble described it as Victor Trumper’s capacity for listening politely and attentively to all advice but going his own sweet way”.

As Victor Trumper’s will to succeed at cricket was nurtured by an external force, we are left with the question of why cricket attracted his attention more than other sports – though Peter Lloyd doesn’t offer an insight on this particular matter.

At this stage in his review, having just emphasised the “vulnerability” of the generic family of inner Sydney to economic fluctuations and environmental pressures, it seems that Peter Lloyd may have come under the influence of some kind of mind expanding substance or perhaps became light headed with exhaustion from doing all this writing. He proceeds to ramble on about braches of scholarship describing the dismal realities of life in those times. To quote him verbatim:

“Several disciplinary branches of Australian historical scholarship provide an impressively detailed and compelling theoretical body of work which describes and explains the grim realities of the final quarter of 19th century urban life for the working classes. Researchers include those with a focus on urban studies, social geography, social collectives, economic history, labour politics and the working classes, poverty, feminist history, transport and the family. Some names that spring readily to mind include Jenny Lee, Shirley Fitzgerald, Max Solling, Christopher Keating, Brett Lennon, Garry Wotherspoon, Max Kelly, Eric Fry, Michael Gilding, Jill Roe and Robin Walker. And the list goes on.”

Peter Lloyd continues, somewhat loftily:

“It would have been useful for Bonnell to allude to the work of at least some of these diligent researchers and capable authors in contextualising the circumstances of Victor Trumper’s prodigious early cricketing stature… Two examples, below, suffice to suggest how such inclusions might have enhanced his account.”

By now I feel that Mr. Lloyd may have been in urgent need of medical attention! Though he battled on manfully, seemingly in subconscious mode. We are treated to:

…pedestrianism…horse-drawn carriages…a desire to know the number of tradesman working in the shoe industry…and what the typical wage of a factory hand was. And, to cap it all off, he refers to an estimate made of the total output of boots and shoes in Sydney in 1870.

This material comes before telling us something of greater relevance – though it’s only an inconclusive snippet – concerning the wages paid in the boot and shoe trade, being the sector that Victor Trumper’s father was active in for a long while. In running his own business, as Peter Lloyd points out, success would have been “heavily dependent on the capacity to restrain manufacturing and labour expenses.”

Some six paragraphs later, Peter Lloyd returns to the subject of Victor Trumper’s ascendancy to cricketing grandeur, though this time he poses the question of how this occurred given his socially humble beginnings. After some rather patronising praise of Max Bonnell’s depiction of the eagerness of young Victor to join in local cricket practice sessions and his emergence at club and then representative level, following school match performances, Peter Lloyd highlights what he views to be a “missing contextual feature” which is revealed to be “the increasingly significant concept of contested sport, and recreational physical exercise more broadly, as an important element of popular culture.”

At this juncture, I would ask you – the reader – to check my quotes against the text of Peter Lloyd’s review to assure yourself that I’m not just making up this stuff!

As he drones on, we are given mentions of:

…patterns of housing, work and consumption…Richard Waterhouse contending…community identity and status… particular aspirational values and competitive attitudes attached to participating in contested games or watching others play…

Building to a crescendo, Peter Lloyd highlights:

“Qualities such as setting goals, undertaking hard work, and testing oneself through personal risk and sacrifice …becoming important features within the social and cultural milieu among the working-classes of colonial society.”

Perhaps in the wake of a harrowing nightmare about Max Bonnell’s potential, or likely, reaction to what he has written, in closing Peter Lloyd is at pains to emphasise:

“…this reviewer has nothing but praise for Bonnell’s excellent crystallisation of the known circumstances of the formative years of Victor Trumper and for the additional details that he’s uncovered which add immeasurably to the information base about the cricketer’s early life.”

To conclude: I feel that Peter Lloyd’s bloated review has, ultimately, been self-defeating in putting forward a couple of suggested enhancements to Max Bonnell’s short book. Perhaps he inwardly acknowledges this as he awards the book the maximum possible rating – 5 stars!

All of what Peter Lloyd says that is of direct and significant relevance to Victor Trumper could, in my opinion, have occupied one side of A4 paper.

THE END

Comment by Caroline Hendry | 10:42am GMT 13 March 2025

I’m giving this follow-up note by me, Caroline Hendry, the title: ILLUMINATION.

It occurred to me in hindsight – having some days ago posted my comments on Peter Lloyd’s review of Max Bonnell’s new book, Young Vic – that perhaps a few members of cricket history’s cognoscenti have been mulling over the possibility that my surname is connected in some way with the former NSW, Victorian and Australian team player, HSTL (“Stork”) Hendry. To satisfy their curiosity, I can disclose the fact that I am Stork Hendry’s great grand-daughter. He would tell me, as a youngster, many intriguing stories about his life and those of some of his friends. As a nine year old, I attended his funeral in late-December 1988, Stork having passed away at the advanced age of ninety-three.

My strong desire to put matters straight in my submitted comments arose from the fact that Victor Trumper and my great grand-father, respectively, played the game during immediate pre and post WW1 times. Trumper playing his final first-class match just four months before hostilities began – doing so on 24-27 March 1914, for Australia against New Zealand at Auckland (making 84 in his one innings), this being when Stork Hendry was 18 years and 10 months old. And Stork starting his cricket career at state level twelve months after WW1 had ended, doing for New South Wales on 21-22 November 1919.

It is likely that my great grand-father (who lived in Sydney until the mid-1920s) watched Victor Trumper bat on a number of occasions for New South Wales and when playing some matches in Sydney grade competition. And also in one or two Test matches. If present, as a sixteen year old he would have enjoyed watching Trumper bat against England at the SCG in December 1911 – making a century at number 5 in the order – and two months later scoring 50 runs when opening the second innings against England, fronting up to another legend – the 38 year old Sydney Barnes, still with another ten Test matches ahead of him over the next two years.

And as an eighteen and a half year old, perhaps watching Trumper bat for NSW against the New Zealanders on a Boxing Day fixture in 1913 (though compiling only 33 in his one innings).

It is also entirely possible that Stork was introduced at some stage to the great man. There would likely have been a good number of opportunities for this to have taken place at club grounds during some of Trumper’s First Grade cricket matches for the Gordon side from the 1909/10 season through to the initial four matches of season 1914/15, Stork then being of age 14-19.

The details are contained in Renato Carini’s book The Genius (2018), which I’ve looked through these past couple of days. (It has a revealing way of dissecting Trumper’s record at Test, State and club level, leading to plenty of interesting insights.) Taking one or two highlight scores in each of those six seasons, Stork may well have watched Trumper play some of these innings:

Jan 1910: 87 vs Glebe at home (Chatswood)

Feb 1910: 105 vs Balmain at Birchgrove (in a team total of 186)

Nov 1910: 81 vs North Sydney at home

April 1911: 79 vs Burwood at SCG

March 1912: 71 vs Middle Harbour at home

Oct 1912: 118 vs Sydney on the RB Oval (in a team total of 230)

Dec 1912: 127 vs Cumberland at Parramatta

Sept 1913: 84 vs Paddington at Hampden Park

Nov 1913: 122 vs Sydney at home (in a team total of 276)

Oct 2014: 123 vs Glebe at Wentworth (in a team total of 269)

The Grade cricket matches during this period, Carini tells us, were often more competitive than NSW’s generally one-sided inter-state matches, with the cream of the State’s talent spread around the twelve sides.

On a separate matter, since commenting on Mr Lloyd’s review I have been pondering whether the “showy” nature of his suggested elaborations of the book might, conceivably, be a precursor to an attempt to build on his earlier highly visual tour through Victor Trumper’s cricketing life and times. That is to say, be a forerunner to an endeavour to produce something that could be billed as a thorough-going, comprehensive, biography of the great man. In effect, using his review of Max Bonnell’s book to whet the appetites of potential buyers of whatever he might ultimately produce.

May I say that, in my view, this would seem to be a somewhat misplaced and risky assignment. The Victor Trumper 2015 centenary seminar papers (subsequently published as a single volume which I have looked through) show there is a great deal already written about his life and times and cricket career, his capabilities and uniqueness – articles and books written from different and complementary angles. It is hard to imagine that anything new could emerge, no matter how diligently Mr Lloyd might search. Certainly no video footage of Trumper actually batting in a Test or Sheffield Shield match, nor during a club match. Perhaps one or two minor documents, such as letters written to cricket authorities or friends and relatives, might emerge – with luck. Though that’s about it, I would guess.

It seems also that there is quite a risk attached to such an endeavour. If nothing really significant by way of new material is turned up, Mr Lloyd could be at the mercy of a latter-day Major Rowland Bowen – the guardian of book readers with his forthright and often stinging new book reviews in the Cricket Quarterly journal – which, I learn, ran from 1963 through to 1970 with a total of 32 issues. I came across this Major Bowen gem condemning Ronald Mason’s book, Sing All a Green Willow (published in 1967):

Although the ideas which gave rise to his essays are often well conceived…

we can only consign this book to that sadly growing pile of rubbish which the cricket publishers have been so bent on increasing.

This drop of acid being followed by a disparaging comment about the price of the book.

Yet I find that Martin Chandler, for one, had nothing adverse to say about these essays on notable players when reviewing Ronald Mason’s whole oeuvre in a piece written in November 2019 (posted on this website).

On reviewing a new, claimed to be comprehensive, Trumper biography, a harsh critic might well weigh in with a tersely dismissive: Another wholly unnecessary book!

Also, in teasing out his proffered elaborations of Young Vic, Mr Lloyd has now given away part of his own potential contribution. So I really do think he will be wise to give such a venture a wide berth.

Comment by Caroline Hendry | 12:11am GMT 20 March 2025

Caroline Hendry’s observations and historical context are fascinating.

Comment by Tom Clark | 8:36am GMT 26 March 2025