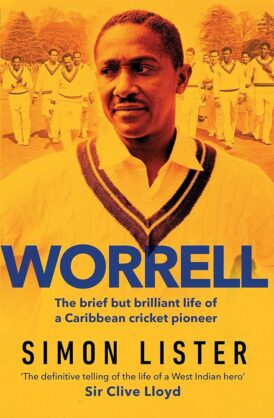

Worrell: The brief but brilliant life of a Caribbean cricket pioneer

Martin Chandler |Published: 2024

Pages: 416

Author: Lister, Simon

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Rating: 4.5 stars

Almost a year ago to the day I posted a review of Vaneisa Baksh’s Son of Grace. Conceding immediately that it is something I have a tendency to do anyway, in that case I felt it a useful exercise to set out at the start of the review a summary of previous writings on the subject of Frank Worrell. This is what I wrote then;

The name of Sir Frank Worrell shines out like a beacon from the annals cricket history, he is universally regarded as a great cricketer and leader of men. But despite that Worrell remains, for those interested in him, a source of some frustration as whilst his achievements on the cricket field are well chronicled the essence of the man remains elusive.

There have been books, the first of them an autobiography, Cricket Punch, published in 1959. As books of its type go it isn’t bad, but it reveals little of its author, and in any event it was published prior to his taking over the captaincy of the West Indies team.

In 1963, just after Worrell’s retirement, the Guyanese broadcaster Ernest Eytle published Frank Worrell, a biography to which its subject provided a commentary. That one is very much a cricket book rather than anything more wide ranging.

After Worrell’s tragically early death in 1967 there were two slim books published in the Caribbean, by Undine Guiseppe and Torrey Pilgrim, in 1969 and 1992 respectively. Neither added a great deal, although in 1987 a very slim biography, also titled simply Frank Worrell, appeared from English writer Ivo Tennant. That is better, and is certainly more than a review of a cricket career, but still not the complete package.

I was aware at the time that Simon Lister, biographer of Clive Lloyd and the author of a masterly study of the development of the all conquering West Indian side that Lloyd put together, was also working on a biography and that one has now been published as well. Thus Worrell’s life has been the subject of two detailed accounts in the space of just a year more than half a century after his passing, a fact that of itself underlines his importance and, perhaps, indicates why a thorough understanding of Worrell has proved elusive in the past.

By their nature both books cover the same ground, so there is inevitably a question as to whether both are a necessary investment for the many who remain interested in Worrell to this day. Lister had the benefit, which he freely acknowledges, of reading Son of Grace as part of his research, but I am pleased to report that there are more than sufficient distinctions between the two books to justify any reader investing in both. The pair complement each other more than they compete.

To quote myself again one observation that I made on Son of Grace was throughout the book the story remains one of Worrell the man rather than Worrell the cricketer. The two are of course inextricably linked, but Worrell is very much more a ‘cricket book’ than Son of Grace.

There is another significantly different perspective in the two books. Baksh is and always has been based in the Caribbean whereas Lister is English. For long periods both the Caribbean and England were home for Worrell, and whilst neither writer has in any way skimped on the ‘other’ side of the story there are inevitable differences of emphasis.

As an example in Worrell Lister tells one particularly memorable story, that of Siggy Cragwell. Born in Barbados in 1939 Siggy came to the UK to work on the railways, something he continues to do after more than sixty years and, now in his eighties, he still plays cricket. He was there at the Oval in 1963 when Worrell played his final Test, and his memories of that game and his life in England are nothing short of priceless. If Lister finds himself with time on his hands in the coming months then having given us such a tantalising taste of it he would do well to assist Siggy to get his life story into print.

In terms of the writing of Worrell the research that has gone into it is hugely impressive. The bibliography extends to eight pages and there are an impressive list of names in the acknowledgments, as well as an explicit acknowledgment of the importance of Son of Grace.

Lister’s epilogue captures the essence of what he had to deal with very well when, referring to his subject’s arresting duality, he describes the fervent Anglophile who endorsed the Nationalist project; the hard-drinking late-nighter who forbade card-playing; the suave diplomat who bore a chip on his shoulder; the cheating husband who was a paragon of decency, the Black captain who repudiated the extent of the colour bar, the beautiful bat for whom Test tons could mean little.

It follows from all that I have already written that I give Worrell a ringing endorsement, but it is not quite perfect. Given the emphasis of the book, and conceding that it has an excellent selection of photographs and a ‘proper’ index it would have benefitted from at least a summary of the stats of Worrell’s playing career.

The responsibility for the lack of a statistical appendix lies, I suspect, at the publisher’s door as I would think does the rather jarring sight on one occasion of ‘British Guiana’ being referenced as ‘British Guyana’, and the name of the Australian left arm wrist spinner who featured more than once in the famous 1960/61 series appearing as ‘Klein’ rather than ‘Kline’ in a couple of places.

I am not so sure about where the blame lies for the one ‘continuity error’ in the book however. Anyone familiar with Farokh Engineer will know that, in the manner of his fellow Lancastrian Neville Cardus, he is not a man to let the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth get in the way of a good story. But I doubt even he claimed to have been touring the Caribbean as a fourteen year old in 1952/53, and that somewhere between the cutting room and the typesetter his tale of his meeting Worrell during the Indians’ 1961/62 tour of West Indies has got into the wrong chapter – that much said like all of Rookie’s stories, apocryphal or otherwise, it is a very good one.

I liked both books a lot. But Lister has Wes Hall worried about the position of his front foot in 1960, more than 2 years before the front-foot law became operational.

Comment by Chris Caton | 11:15am GMT 29 December 2024