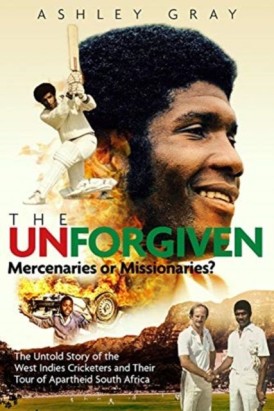

The Unforgiven

Martin Chandler |Published: 2020

Pages: 256

Author: Gray, Ashley

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 5 stars

Who remembers Lawrence Rowe? The reality is that for any cricket enthusiast who was around in the early 1970s his is a familiar name, but that is about it. The blistering start to his career is occasionally recalled, but more often it is the eye problems and the comedic value of the grass allergy that are mentioned. Even his leadership of the two West Indian rebel tours of the early 1980s tends to be forgotten.

Unlike the trips undertaken by the English and Australian rebels in the same era interest In the West Indian tours has taken off in recent years. The sad stories of the wretched declines, through alcohol, other drugs and mental health issues of the likes of Richard “Danny Germs” Austin , David Murray and Herbert Chang have all attracted interest, and their stories have taken a number of writers and journalists to the Caribbean.

Foremost amongst those looking into what became of the West Indian rebels is Australian Ashley Gray and his book, entirely appropriately entitled The Unforgiven, is a long hard look at the lives of the twenty black cricketers whose lives were profoundly affected by their decision to take a handsome pay day in return for taking a trip to a land where they were, despite their outstanding sporting talent, regarded in law as second class citizens.

There is a hard hitting introduction to The Unforgiven which spells out the situation in South Africa at the time, the reasons why the tour took place, and the cloak and dagger moves that went on to arrange them. The rights and wrongs of the argument are not however the subject of Gray’s book, at least not directly and nor indeed, other than in passing, is the very competitive cricket that was played throughout both trips. The book concentrates very much on the lives of those involved and its power lies in the twenty individual stories that feature many examples of human strength, and just as many of our frailties.

Appropriately enough the twenty chapters begin with Rowe, and a reminder as to just what a massive talent he was when he first burst onto the Caribbean cricketing scene. I must have seen him in 1976 when he played twice in England but by then his career, from an initial high that was almost Bradmanesque, was already on the way down. The promise he had shown as a youngster and his ‘leadership’ of the rebels no doubt added to the strength of feeling that was directed against him for what he did, but he at least managed to survive, relocated to the US, and has seen later life treat him pretty well. His story an absorbing one, very well told and it whets the appetite for the following nineteen.

A fine example of the lengths that Gray went to gather the back stories of the rebels is in the chapter concerning Bernard Julien, a man who was at one time hailed, not without cause, as the new Sobers. In the end for reasons that Gray carefully and sympathetically records his career disappointed, but there were some fine performances along the way.

Julien was one of those whose international career was effectively over by the time of the rebel tours. Gray was successful in speaking to him over the telephone, briefly, on a number of occasions and visited Trinidad for a meeting that never took place. He certainly tried had to make it happen though, that journey being a decent tale in itself. If Gray was frustrated at not actually meeting his man he can at least rest assured that such was the information that he gathered along the way that it is unlikely to have made a great deal of difference to the quality of the chapter on Julien had he succeeded in meeting his man.

After an unpromising beginning in his search for him Gray was able to meet with off spinner Albert Padmore, who has lived in Miami since 1986. Padmore was one of the three spinners who could not prevent India successfully chasing more than 400 for victory in Port of Spain in 1976, a result which convinced Clive Lloyd that a pace battery was the key to success in Test cricket. Padmore’s take on that and the background to his departure for the USA are the most rewarding parts of a little known story.

One man who did have an international career after the rebel tours was Monte Lynch. England qualified Lynch was persuaded that, having been overlooked by the West Indies selectors, it was in his interests to join the second rebel trip. Five years later in 1988 he was selected to play for England in three ODIs against West Indies. I vividly recall being present at the Lord’s match and having a most enjoyable day in the company of a number of West Indian supporters, who were exhilarating company and deeply knowledgeable about the game.

The depths of the scars inflicted by the rebel tours, which I had long forgotten by then, was brought sharply into focus for me when, for a couple of overs, Lynch came out to field on the boundary close to where we were all sat. The change in my new found friends was palpable and the hostility demonstrated by them towards Lynch went far beyond the sort of banter you would expect simply as a result of a Guyanese born man playing for England. Thirty years later Lynch was happy to share his life story with Gray, and a thought provoking one it is too.

One man who I was particularly looking forward to reading about was Ray Wynter. A First Class career of just 18 matches altogether and a description on Cricketarchive as ‘fast medium’ has always suggested to me that he was something of a makeweight. He went on the first tour, but was surplus to requirements for the second albeit he still received his contractual payment. In fact it seems that he was genuinely fast and certainly extremely hostile. His story is slightly different from his fellow tourists in that he seems, the suggestion being because of his lower profile, not to have attracted quite as hostile a reaction from his fellow West Indians as the others and, having spent a number of years in the US in between, he is now back in Jamaica enjoying the fruits of a successful career outside the game, kickstarted by the money he made from the tours.

All of Gray’s essays contain something of note. There is a bittersweet account of the life of that great fast bowler, Sylvester Clarke, and the accounts of the torment of men like Chang, Murray and the late ‘Danny Germs’ are compelling. The essay on Austin shows just how long Gray has been working on this book, as it is assisted by an interview with its subject who, as the reader learns, died more than five years before the book was published.

I could go on waxing lyrical about The Unforgiven for a while yet, but the reality is I would be wasting my time and yours. Having given a flavour of what readers can expect from Ashley Gray’s first book I would encourage every one to go and buy a copy. Gray has added a fascinating book to the literature of our great game, and comfortably earns our top ranking.

Hi Martin. Would you be able to correct the Author’s surname in your review? It’s not Young.

Comment by Mitchell Hall | 10:50am BST 26 April 2020

Hi Mitchell, this is done, thanks for letting us know.

Comment by James Nixon | 11:31am BST 26 April 2020