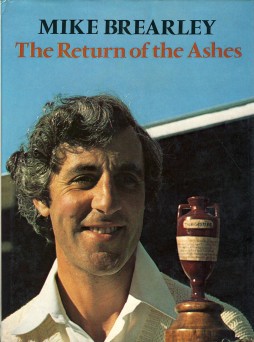

The Return of The Ashes

James Gee |Published: 1978

Pages: 160

Author: Brearley, Michael and Doust, Dudley

Publisher: Pelham Books

Rating: 4.5 stars

The Return of the Ashes is an excellent book co-authored by former England captain Mike Brearley. For the uninitiated, Brearley was a very shrewd captain who was aptly described by Rodney Hogg as “having a degree in people”. This book, Brearley’s first, showcases writing skills of the highest order and is a very engaging read.

The primary focus of The Return of the Ashes is the 1977 Ashes series in England, won 3-0 by the home side. For this work, Brearley collaborated with the late Dudley Doust, a Sunday Times journalist. Doust was an American who relocated to England and who was previously unfamiliar with cricket before he interviewed Brearley during the Headingley Test of this series, a discussion which (thankfully) eventually led to this book being written. Brearley and Doust joined forces again for the The Ashes Retained (1979), another superb book, which examined England’s landslide 5-1 win in the 1978-79 Ashes on Australian soil.

The perspective of the book transcends the 1977 Ashes and the World Series Cricket developments, breaking news in mid-1977, are evaluated in astute style. I will have a more detailed look at Brearley’s views on World Series Cricket later. Brearley, who was also captain of Middlesex at the time, covers key points of his county’s 1977 campaign in succinct fashion. Middlesex’s triumphs in the County Championship (joint winners) and the Gillette Cup were icing on the cake of Brearley’s success in the Ashes. As an Australian cricket follower, the fact that Australia lost the Test series convincingly did not detract from my enjoyment of the book.

The book begins in earnest with England on the verge of recapturing the Urn in the Fourth Test at Headingley (where else?). Australia were 9-248, with Rod Marsh hitting out with only the tail for company. On page 10, Brearley gives an incisive analysis of Marsh’s batting traits and the merits of Brearley’s field placings. The form and mindset of the bowler, Mike Hendrick, are described. Brearley explains the moment so vividly that one can readily visualise the sequence of events that resulted in Marsh top edging a ball to Derek Randall at mid-off, thus sealing the destination of the Ashes. This is the first example of many passages of lucid and absorbing writing that bring the on-field action to life.

In contrast to many books that cover Test series, The Return of the Ashes does not take the easy road of rehashing the on-field events blow-by-blow and restating public commentaries of the day. The authors are judicious in their selection of focus: important parts of the series are put under the microscope and interesting facets are revealed, while other elements of the matches are covered in a high level manner. This approach allows the momentum of the writing to be sustained, avoiding potentially dull descriptions of play that could be adequately discerned from the scorecards.

The authors maintain eloquence without falling into the common trap of using unusual or long words that would require most readers to resort to a dictionary. The language used is accessible throughout. A great success of The Return of the Ashes is that the authors frequently analyse a topic in detail while at the same time maintaining a lively and concise prose. The rigour of analysis is not at the cost of long and tedious passages of text. A case in point is Brearley’s analysis of the merits of Derek Underwood bowling over the wicket to Australia’s right-handers to utilise rough patches near leg stump (see pages 49 and 51-52). Brearley examines the field placing possibilities and some potential problems. Eventually, he persuaded a reluctant Underwood to apply the tactic, which led to Underwood claiming 6-66 in Australia’s second innings in the Second Test at Old Trafford. This situation also demonstrated Brearley’s excellence in understanding what makes people tick, showing empathy and bringing out the best in them.

The Return of the Ashes also displayed Brearley’s capacity for lateral thinking. On page 19, he recalled his experience of bowling a spell of underarm deliveries in a county match and he concluded: “there is no reason under-arm bowling shouldn’t come back. It is a good, freakish variation if you are stuck”.

Turning to World Series Cricket, Brearley takes a balanced and measured approach. He does not condemn his international cricket colleagues (which included teammates Greig, Knott, Underwood and Woolmer) from partaking in the comparative riches of Packer’s competitions. He understood that World Series Cricket would offer financial security to players in an environment where cricket earnings were modest and on-going selection for the national side was uncertain, particularly for players well into their careers. Brearley saw potential merit in innovations such as cricket under lights and drop-in pitches, but he emphasised the need for caution and not disregarding other possibilities. He opposed fielding restrictions and microphones near stumps. Brearley described his philosophy here as being for reform, but not revolution. Brearley implied that World Series Cricket could co-exist with establishment cricket, provided that schedules didn’t clash. He viewed bans on World Series Cricket players from playing first-class cricket as unfair. He cited the example of Underwood, who was banned by his county, Kent, for having signed a contract to play World Series Cricket for a period that was outside the period he was employed by his county.

In relation to the potential for World Series Cricket to appeal to the public, Brearley (writing in November 1977) was sceptical of the notions that the Australian public would be guaranteed to support the Australian World Series Cricket XI and that spectators would turn up in large numbers to see the world’s finest cricketers (see page 95). This observation showed significant foresight. In World Series Cricket’s first season of 1977-78, the attendances at many World Series games were low and the public tended to support the official, albeit weakened, Australian Test side in their hard-fought 3-2 series win over India. Brearley picks up these observations in his writings from February 1978 (page 97). Brearley adds that he is not in favour of players coming in and out of Test teams when it suited the country or the player.

A delightful feature of The Return of the Ashes is the photographs and, in particular, their captions. Most of the photographs were taken by legendary Patrick Eagar. The enjoyment of the photographs is accentuated by Brearley’s pithy and erudite captions. A case in point is the caption on page 50, which shows Doug Walters being caught adjacent by Tony Greig. Brearley provides an illuminating explanation of why he chose to bowl Greig in the last over before lunch and a dissertation of why Greig opted to bounce Walters early in the over. Another terrific example is the detailed caption on page 52, which pictures Greg Chappell playing on to Underwood, bowling over the wicket into the rough outside leg stump. A feature of this caption is the explanation of Alan Knott’s wicketkeeping technique. Nirvana for the true cricket nerd.

After the drawn Fifth Test at the Oval is covered, the narrative section of the book comes to a close with an enlightening chapter of perspectives. Brearley evaluates the performances in the series of the Australian and English sides. In relation to the impact of the World Series Cricket ructions on the Australian camp, Brearley opined that “it is sheer speculation to say that Packer’s spectral presence contributed to Australia’s defeat”; and “I am sure that Chappell and his side set out as would any other self-respecting team, saying, in effect, ‘if this is our last fling, let’s show them’” (pages 105-106). Brearley attributed England’s superiority in the series to excellent bowling, better depth in the bowling ranks, fielding (especially close catching) and, possibly, greater determination in batting. Brearley pays tribute to his predecessor as England captain, Tony Greig, who was able to put aside losing the captaincy before the series and, in support of Brearley’s leadership, “could not have been more helpful” (page 108). Brearley offers some ideas about the role of captain (a possible entrée to Brearley’s seminal work on cricket captaincy, 1985’s The Art of Captaincy?) and he reflects on a personally successful 1977.

A positive feature of The Return of the Ashes is the appendix of statistics near the end of the book. The appendix details the close of play scores for each day of the Test series, with a complete scorecard for each innings that ended on the relevant day. The use of day-by-day scorecards enhances the reader’s ability to understand the flow of the match and to read the scorecards in conjunction with the narrative.

The Return of the Ashes is a terrific book. It is a vital addition to a cricket library alongside Brearley’s other books The Ashes Regained, the magnificent Phoenix from the Ashes (1981 Ashes) and the must-have The Art of Captaincy.

Leave a comment