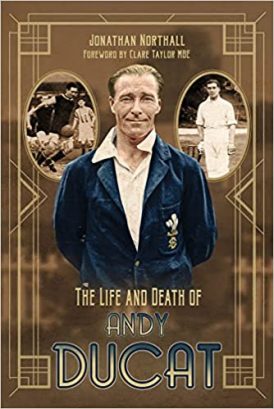

The Life and Death of Andy Ducat

Martin Chandler |Published: 2022

Pages: 255

Author: Northall, Jonathan

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 4 stars

There is something particularly interesting about the double international. In my youth there many of us who dreamt of a life of professional cricket in the summer and football in the winter. It was still possible to do that then, albeit by that stage in the development of the two sports only a few did. As the football season increasingly encroached on the summer top class footballers rarely played cricket as well, but a few county cricketers did play some football, men like Ted Hemsley, Phil Neale, Chris Balderstone and Arnie Sidebottom, the latter two even managing to win Test cap – for batsman Balderstone there were two against the 1976 West Indians, and for fast bowler Sidebottom one against Australia in 1985.

In the more distant past managing two careers had been easier, and all told there have been as many as thirteen double internationals. One of them is a latter day sporting heroine, Clare Taylor, who contributes a perceptive foreword to Jonathan Northall’s biography of one of other twelve, Andy Ducat, of Surrey, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Fulham and England.

The last two male double internationals began their careers in the 1950s, and both have been the subject of biographies in recent years, Willie Watson and Arthur Milton. Of their predecessors books also exist on the lives of Jack Sharp, Harry Makepeace, ‘Tip’ Foster, William Gunn and Alfred Lyttelton, and there are several on the subject of the one legendary figure amongst this elite club, Charles Burgess Fry.

Ducat was born in 1886 and won three soccer caps before the Great War. Already thirty three when sport resumed after the war Ducat enjoyed his greatest success in the early 1920s. On the football field he won three more caps, and was one of the 33 men to be given a game in the selectorial merry-go-round that was 1921. Scores of 3 and 2 meant Ducat was discarded after that single match, but his form over the post war years was such that had any Test cricket been played in 1919, 1920, 1922 and 1923 he would surely have added to that single cap. As it was injury meant he missed the whole of 1924 and the chance to play against South Africa, and he had turned forty by the time the Australians, this time without Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald, returned in 1926.

Not that turning forty affected Ducat’s county form as he remained a key member of a strong Surrey batting line up until 1931 when, in somewhat controversial circumstances, he was not retained. After that Ducat did some newspaper work, wrote an instructional book and then joined the staff at Eton College before, in 1942, tragedy struck and Ducat suffered a fatal heart attack whilst batting at Lord’s for the Surrey Home Guard against their counterparts from Sussex.

One thing that is not clear from The Life and Death of Andy Ducat is exactly what sparked Jonathan Northall’s interest in his subject, but what could not be more obvious is the effort that has gone into the research for this project. The detail that Northall has managed to gather regarding Ducat’s career in both sports must have taken many, many hours of trawling through contemporary newspaper reports, local and national.

There are occasions when the linear approach to sporting biography can grate somewhat, yet despite consisting in large measure of such an approach Northall’s writing holds his reader’s interest. One of the reasons for that is the straightforward one that I am not used to reading about footballers’ careers, and therefore doing so makes a refreshing change. Another is the fact that Northall does not, as some in the past have, simply reproduced the match descriptions written long ago by others without attempting to add some context to what he has read.

One obstacle that was in Northall’s way was the fact that no one alive today who knew Ducat was available to him, nor was he able to trace family members who might have caches of memorabilia. The result is that the real Andrew Ducat remains a little elusive, although it is clear from contemporary writings that he was a scrupulously fair competitor who seems to have been universally liked. Perhaps the lack of a bit of ‘mongrel’ about him was the reason he did not achieve a little more than he did on the field, and I have no doubt that his amenable temperament and demeanour would have been behind the only failure in his professional life, his tilt at football management with Fulham.

For those interested in how professional sportsmen led their lives in the early years of the twentieth century The Life and Death of Andy Ducat is highly recommended and, albeit right at the end, it also deals with one important point. Ever since I was a child I have, on those relatively few occasions Ducat has cropped up in conversation, pronounced his name ‘Duckat’, and no one has ever corrected me – in fact I now learn, from words written by the man himself, that it is ‘Dewcat’, so thanks to Jonathan Northall I must now change the habits of a lifetime – I am sure I will not be alone in that.

Er, Jack Gregory was, in fact, on the 1926 tour (although the slow, wet pitches and his dodgy knee handicapped him significantly).

Comment by Max Bonnell | 11:43am BST 15 May 2022