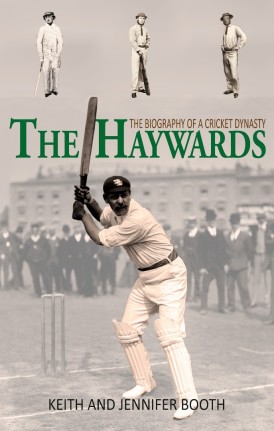

The Haywards

Martin Chandler |Published: 2017

Pages: 347

Author: Booth, Keith and Booth, Jennifer

Publisher: Chequered Flag

Rating: 4 stars

I have been a cricket lover all my life. My earliest memories are of sitting with my father and bombarding him with questions about the game. Whilst he was a way from being what I would now describe myself as, a cricket tragic, he was always happy to watch the game with me and indulge me by answering questions. In addition he had a modest collection of post war Wisdens, that I was allowed to read whenever I wished.

I spent hours with those Wisdens, and when reading them was a very quiet and undemanding child, so much so that from 1965 onwards the Almanack was purchased on publication every April. In those days I always viewed cricket as having started in 1864, simply because I knew that was the year Wisden was first published. My belief was reinforced by the fact that the list of County Champions in the records section of the Almanack, in those days at least, started with that year.

Gradually I learnt more and, thanks to a kindly relative, a first cricket book of my own appeared, a schoolboy history of the game. I learned that in fact the origins of cricket significantly pre-dated 1864. The book wasn’t a detailed one however, and it was to be many years before I started to learn much about men like Fuller Pilch, ‘Silver Billy’ Beldham and Alfred Mynn. Even now however I regard 1864 as a watershed, and everything before that as cricketing pre-history.

Three generations of the Hayward family have figured in the annals of the game, covering a period of the best part of a century, stretching well back before John Wisden launched his publishing venture. Through my childhood reading I knew something of the youngest of the family to grace the game, but until I read Keith and Jennifer Booth’s very welcome book my knowledge of the older Haywards did not extend much beyond the simple fact that there were three more who had played the game at First Class level.

Thomas Walter Hayward, known as Tom, was the second man after WG Grace to record a hundred hundreds. With more than 43,000 runs to his name (not to mention getting on for 500 wickets) he was one of the leading figures of the Golden Age (a loosely defined period usually viewed as being between 1890 and the outbreak of the Great War). There were 35 Test caps for Tom Hayward, although his average of 34.46 is not a remarkable one, even by the standards of the time.

The real stars of the Golden Age were the amateur batsmen, and names like Fry, Ranjitsinhji, Grace, MacLaren and Jackson still shine with the same lustre they had more than a century ago. As a professional batsman Hayward’s reputation, along with those of the likes of Bobby Abel, Arthur Shrewsbury and JT Tyldesley, stands a respectful step or two beneath those luminaries.

No one has written a biography of Hayward before, which is part of the reason why his forebears remain little known. His father, Daniel the Younger, played 43 First Class matches between 1852 and 1869, and his uncle, Tom the Elder, played in 118 between 1854 and 1872. Before them the patriarch, Daniel the Elder, appeared in 24 matches now reckoned to be First Class. The Haywards tells the story of each of the four in turn, and also references various other members of the family who played the game to a decent standard.

The research that has gone into the book is impressive to say the least. The fact that the internet has made it much easier than in the past to access newspaper archives results in more material being available to writers than ever before, but even so I cannot believe that there are any pebbles, let alone stones, that the Booths have left unturned. What they have sadly not had the advantage of is being able to speak to any descendants, Tom the younger not having had any children.

The accounts of the cricketing careers of The Haywards are as comprehensive as a reader would expect. The Booths have gone to all the contemporary reports, some of which are quoted from at length, in order to reconstruct their deeds on the field. But how well have they managed to capture their subjects’ personalities?

To a greater or lesser extent the characters of all four of The Haywards remain elusive, but there are insights throughout the book, especially for those who have any interest in legal matters. Tom the Elder seems not to have been a particularly pleasant individual, and although he earned a good living he knew how to spend money as well, and died penniless. The book contains a full account of one particular piece of litigation where he tried to pursue an associate for a share of the proceeds of a successful bet, the audacity of which, given that he didn’t contribute to the stake, astonished me – unsurprisingly he lost.

As for Tom the younger he too was no stranger to the courts, although the details of his main clash with the English legal system were not comprehensively reported at the time. Young Tom was, similarly to his eponymous Uncle, clearly not the best with money. This was demonstrated in 1905 by the outcome of an action brought against him by an Australian woman for breach of promise of marriage. It is unfortunate for 21st century readers that Tom’s anxiety to avoid as much adverse publicity as possible persuaded him to settle the case out of court at an early stage. The reader of his biography is left with a ghoulish curiosity as to exactly what the nature of that claim was given that it prompted him to pay a sum in damages sufficient to require him to go cap in hand to the Surrey club for financial assistance.

Unlike his uncle however Tom the younger rebuilt his finances, in part thanks to his wife not being without means. Tom was 42 when he did eventually marry, in the January of the year that turned out to be his last season, 1914, and the marriage seems to have been happy enough. In a time when few women were engaged in such work Matilda Hayward was a detective and, on the basis of the single chapter in The Haywards devoted to her, it is a great pity that she never penned her own memoirs.

Given the authors’ impressive oeuvre of Surrey biographies it is only to be expected that The Haywards should be an interesting and satisfying read, and I have no hesitation at all in recommending it. In addition to the quality of the narrative, and because these are issues that the review team at CW care about, mention must also be made of the extensive bibliography and list of sources, the comprehensive and well set out statistics and an excellent index. The photographs deserve a sentence too as whilst they are not the most exciting, hardly surprising with no family collections to call on, much care has clearly gone into their selection and, I suspect, no little effort given that a photograph of young Tom’s wedding was eventually located.

Finally, I like to think (and it is hinted at in the preface) that I bear just a scintilla of responsibility for the book’s appearance in light of a comment I made in my review of Keith Booth’s biography of Tom Richardson. So in the hope that lightning might strike twice I will take this opportunity of reminding Keith and Jennifer that there is no retirement age for writers, and that I also mentioned William Lockwood in that review, and should have added the name of James Southerton.

Leave a comment