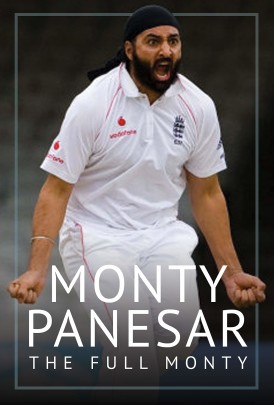

The Full Monty

Martin Chandler |Published: 2019

Pages: 202

Author: Panesar, Monty

Publisher: White Owl

Rating: 4 stars

It’s almost impossible to think of Monty Panesar without smiling, are the first words of The Full Monty, and seldom has a more appropriate comment started an autobiography. Everyone liked Panesar from the moment he first pulled on an England sweater. Forgiving his occasional lapses in the field, and his sometimes disappointing performances with the bat cricket enthusiasts throughout the world warmed to Panesar the moment he demonstrated that whatever he couldn’t do, he could certainly bowl left arm spin, and do so in the old fashioned way with orthodoxy, persistence and skill.

A few weeks ago Panesar turned 37, an age at which the greatest of all masters of the craft of orthodox left arm spin, Wilfred Rhodes, still had sixteen years of First Class cricket in front of him. Yet it is more than five years now since Panesar won his last Test cap. It is almost as long since he last looked like what he briefly was, the best spin bowler in the world, his few appearances in 2015 and 2016 being disappointing. Since then he has not been seen in the First Class game.

As the first Sikh to play for England, and such a popular man to go with it, Panesar’s first autobiography, Monty’s Turn, appeared from a major publisher less than two years after his Test debut. An awful lot has happened to Panesar in the intervening years. There have been highs and lows both on and off the pitch. For several years all was well, with just the occasional disappointment but, eventually, it became downhill almost all the way. As the mental health problems took hold and a marriage failed very quickly Panesar’s cricket career withered on the vine.

Recent books by Marcus Trescothick, Jonathan Trott, Steve Harmison, and Michael Yardy all demonstrate what a tough time cricketers have in the twenty first century, and all of their stories have made interesting reading for the outsider. Panesar looks at all of those former dressing room colleagues, and introduces the travails of Andrew Flintoff and Matthew Hoggard as well. It is striking, if treated as case studies, how different all of those stories are. Until Panesar spelt it out just how challenging it must be to be a medical professional in the mental health field had never really occurred to me.

There was a time when autobiographies were almost always chronological journeys through the writer’s life. In recent years however many have begun with a chapter on a significant event in the author’s career, and Panesar is no exception. Armed with that information the reader might then have expected to be introduced to Panesar’s story by a reference to one of his memorable performances.

There is no shortage of possibilities. First and foremost is probably that remarkable last wicket partnership with Jimmy Anderson at Cardiff in 2009. But other obvious candidates are that first Test wicket, and Panesar’s joyful reaction to trapping the legendary Sachin Tendulkar lbw. Other possibilities might have been his matchwinning 11-210 at the Wankhede in 2012 (including Tendulkar in each innings) or his ten wickets against West Indies in 2007. But no – Panesar’s choice was in the third Test of that 2005/06 series in India when, as England closed in on victory, he contrived to lose sight of a steepling catch offered by MS Dhoni, lost it in the sun and failed to even get a hand to it. At least he made up for it a few deliveries later when he held a similar but rather more difficult chance.

Perhaps the point of that introduction was to make sure that Panesar’s reader started the book with that smile firmly fixed on his or her face, and if so it was probably a prudent move given that not everything that follows paints Panesar in the best light. As his life has unravelled Panesar has taken the opportunity on several occasions to, putting it bluntly, behave like an idiot. He doesn’t shy away from those incidents however and, certainly in this reviewer’s opinion, still has plenty of credit left in the bank when the book ends.

Like Moeen Ali’s recent book Panesar is also interesting when it comes to some of the racism he has had to put up with in his life, and no less readable when writing about other situations where he has experienced precisely the opposite. He has some interesting political views, most of which I agree with, but he probably shouldn’t have allowed himself to be drawn on the subject of Indo-Pakistani relations. A couple of paragraphs in a cricketing autobiography is not the right setting for a meaningful discourse on such a complex subject, particularly if you are expressing views which, according to a man I know who does understand the subject, contain only a grain of truth.

Early on in The Full Monty Panesar expresses the hope that his book will have an uplifting effect on his reader. There are certainly some dark corners opened up and explored, but Panesar’s is a fascinating story. It is written in a slightly frenetic style but, and this is always what any writer aims for, the book is difficult to put down. It also helps that while Panesar does throw the odd brickbat, he always gives credit where it is due, and doesn’t simply use The Full Monty as a forum for settling old scores. It is also important that the book ends on an upbeat note, and Panesar certainly achieves his aim. As I closed the book, the smile was certainly still on my face, although nothing like as broadly as it will be if one day the name of Monty Panesar appears on a county team sheet again.

Thanks Martin. Look forward to reading the book now! Right now an ‘import’ item to India!!

Comment by vincentsunder | 3:03am BST 8 June 2019