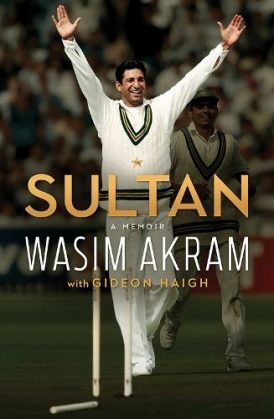

Sultan: A Memoir

Martin Chandler |Published: 2022

Pages: 296

Author: Akram, Wasim

Publisher: Hardie Grant

Rating: 4.5 stars

There are fifteen chapters in Wasim Akram’s autobiography. The first one is prefaced by a fulsome tribute from Pat Cummins, and each of the next fourteen by a similarly effusive quote from someone else, generally an opponent, Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, Allan Border and Steve Waugh amongst them.

Perhaps, as a Lancastrian, I saw so much of Wasim that he became just a bit too familiar, but in any event I have to confess that in the two decades since his playing days ended I had rather forgotten just what a great cricketer he was. Those brief excerpts brought that fact sharply back into focus, and reminded me that Wasim has as strong a claim as anyone to the title of the finest left arm fast bowler the game has seen.

But of course Wasim was much more than just a bowler, and whilst his batting stats probably don’t do his talents in that department justice, no one whose top score in Tests is an unbeaten 257 is a mug with the bat. Wasim was indeed one hell of a player, and for bringing back those memories of days gone by alone I am glad I read Sultan.

Over the best part of twenty years Wasim played in 104 Tests and 356 ODIs for Pakistan, so there is a vast amount of cricket to be described. He played with and against some great players, some remarkable characters, and in some fascinating contests. Much cricket is described and, as all who read about the game will know, there is no man better at recreating cricket matches in the form of the printed word than Gideon Haigh whose undertaking of the writing duties propel the book, almost as a matter of course, to the ranks of the very best cricketing autobiographies.

The Pakistan teams that Wasim was part of had some giant characters. He was very much a protege of and favourite of the biggest of them all, Imran Khan, notably the only non-Lancastrian teammate to contribute one of those chapter introductions. On the other hand there were other compatriots with whom his relationship was much more difficult, and there is no holding back when it comes to describing the high points and the low ones within successive Pakistan dressing rooms.

But, for once with a cricketing autobiography, there is much, much more to Wasim’s story than what happened on the field of play and the success or otherwise of this book, for me at least, was always going to depend on the way in which Wasim dealt with the corruption allegations that were levelled at him, and other players the world over, during his career.

A good deal mud was thrown in Wasim’s direction over the years, not least by some of his own teammates, which makes his observations in Sultan on the dressing room interactions all the more important. It is a matter of record that Wasim emerged from the various investigations with no findings of guilt to blacken his name, but he would have been far from the first man to have come out at the other end of such an investigation less than satisfied with the extent to which he was vindicated, and mutterings about Wasim’s involvement in dastardly deeds have never entirely gone away.

I do not for one moment suppose that Wasim’s own account of the scandals that touched and concerned him will satisfy his sternest critics. After all his account is inevitably exculpatory, and in an autobiography there is no scope for anyone else to express a view or put forward a contrary position. There is no opportunity to cross-examine the author and inconvenient facts and opinions of others can, if necessary, simply be ignored.

So is Wasim’s account a convincing one? Having read it I have to say that with one slight reservation* I believe it is. The first three reasons for this conclusion are all Gideon Haigh. Firstly Haigh’s ability to say what he wants to say with clarity and precision is second to none. Following on from that Haigh is no one trick pony, and in addition to his cricket writing he has also written in the true crime genre, and will have had all the tools he needed to dismantle what Wasim was telling him if he had doubts about its veracity. Finally, and rather more prosaically, I have no doubt but that if Haigh himself hadn’t believed what he was writing were true, then he simply wouldn’t have involved himself in the project.

There are however other reasons why I am happy to accept Wasim’s account, and both of those relate to other areas of the narrative which have inevitably attracted attention, those being his drug taking, and the loss of his first wife. Wasim did not have to go into either in as much depth as he does, and certainly in relation to the post playing career issues he had with cocaine he could easily have spun that in a different way had he so chosen. The obvious honesty with which those two aspects of the story were approached helped persuade me that I could accept the truth of the entirety of Wasim’s account of his life.

So all in all Sultan is a fascinating story of the whole of Wasim’s life, and I express the hope that writing it has proved cathartic for him, and I am certainly looking forward to hearing him in the comms box for England’s forthcoming series in Pakistan. The book is completed by a comprehensive statistical section, an excellent index and a good selection of photographs. It also permitted me the luxury, for the first time ever in a book involving Haigh, of spotting a factual error, albeit one so inconsequential it isn’t necessary for me to dwell on it.

*Wasim admits to making one mistake, in relation to, presumably, conversations with an old friend who, unbeknown to him, had become involved in betting. He doesn’t duck the issue, but the nature of and extent of whatever interactions there were could have been made clearer.

Leave a comment