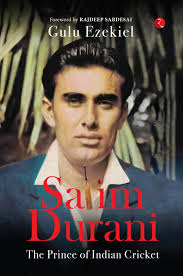

Salim Durani: The Prince of Indian Cricket

Martin Chandler |Published: 2024

Pages: 179

Author: Ezekiel, Gulu

Publisher: Rupa

Rating: 4.5 stars

There are many Indian cricketers from past generations who are deserving of a biography, and I was delighted to learn last year that at long last one of them, all-rounder Salim Durani, was going to be the subject of a book by Gulu Ezekiel. The project has proved to be a thoroughly worthwhile one, Gulu’s research revealing a great deal about Durani’s life and times. I sincerely hope that whilst memories are still intact Gulu and others of India’s fourth estate are inspired now to chronicle the lives of others of Durani’s and earlier generations.

Until now, certainly outside India, Durani’s name has meant little beyond being the answer to the well worn quiz question as to who the first Afghanistan born Test cricketer was, received wisdom being that he was born in Kabul in 1934. That claim to fame, made by others on Durani’s behalf and not by the man himself, was one that Gulu had already exploded in an earlier book, Myth-Busting, so I suppose it was only right and proper that he should then be the writer to give Durani the recognition he actually deserves, for being a fine cricketer and a fascinating man.

Irrespective of where Durani was actually born, and in fairness to him some corner of the Khyber Pass under the open sky is at least as interesting a prospect as Kabul, he has an interesting back story. That tale begins with his father who, as Abdul Aziz, kept wicket for India in one unofficial test in 1935/36, but whose greater claim to fame was being responsible for the cricketing development of Hanif Mohmmad and his brothers. Exactly how Durani’s early life took shape is not as clear as one suspects Gulu might have liked, but he has done very well with the material that he has been able to track down.

As a cricketer Durani was an all-rounder. A dashing batsman with a penchant for hitting sixes he could also, if necessary, dig in and build an innings. With the ball he was much the same, an orthodox left arm spinner who attacked the batsman, relying on spin and variations of pace but, once again if the situation demanded, he could bowl as parsimoniously as his miserly teammate and fellow slow left armer Bapu Nadkarni. Add in to the mix Durani’s matinee idol good looks and a generous nature and his popularity in the 1960s is easy to understand.

Durani’s career falls into three distinct parts. In the early 1960s he was a regular for India and was capped 23 times and in the course of those matches he turned in several stirring performances. Then, after scoring 55 and 17 and bowling economically in the first Test against West Indies in the 1966/67 series, he was dropped. The reason has never been entirely clear, but Gulu advances two theories, Durani inadvertently tripping up one of the selectors in the team hotel or that his captain, ‘Tiger’ Pataudi simply did not want him in his team. The fact that the third part of Durani’s career, which contained his last six Tests, begun in 1970 when the selector concerned was gone and Pataudi was replaced by Ajit Wadekar rather suggests that both of those may well be correct.

As is so often the case injury brought Durani’s playing career to an earlier conclusion than might otherwise have been the case, and after that it would be fair to say that life was seldom straightforward for him and seems to have been something of a struggle. The story of what became of the not inconsiderable proceeds of a benefit match in the UAE is, perhaps, as accurate a summary of just what sort of man Durani was as appears anywhere in his story.

Sadly Durani died in 2023, his passing being the catalyst for the writing of the book. Thus there is no direct input from the man himself, although it would be wrong to say that he had no personal involvement as Gulu did know him and had met him on a number of occasions. He also tracked down a number of interviews given by Durani over the years to different writers and publications and has taken the opportunity of speaking to people who knew Durani well as well as to his former teammates and opponents.

This sort of account of a life well lived inside and outside the game has much to commend it and, as I indicated in opening this review, I sincerely hope other Indian writers will follow Gulu’s lead and that we will see a steady stream of these sort of books in the coming years. All who are tempted to pursue such projects would do well to take a long look at Salim Durani: The Prince of Indian Cricket before starting out. All sources are scrupulously noted at the foot of the page they are referenced on, there is an excellent index, all the important statistics are included and there is an interesting selection of images albeit not all reproduced as crisply as the would be in an ideal world. If I had to find one complaint it would be that the book appears neither in hardback nor as a limited edition, but then there are only a few of us who will be troubled by that one.

Leave a comment