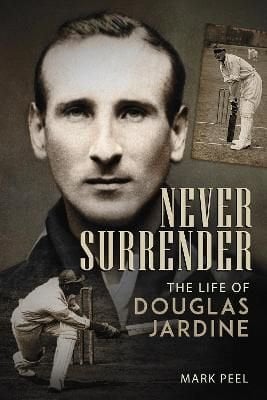

Never Surrender: The Life of Douglas Jardine

Martin Chandler |Published: 2021

Pages: 286

Author: Peel, Mark

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 4.5 stars

Half a century ago Douglas Jardine was a forgotten man. When I was a youngster and first falling under cricket’s spell his was just a name that clung to the bottom of Wisden’s table of the most prolific centurions. Jardine managed 35, the minimum number needed to get on the list in those days. The fact that he had led England to a 4-1 Ashes triumph in Australia was something that, back then, was rarely mentioned.

To those introduced to cricket history in more recent times this will come as a surprise, as Jardine’s name is mentioned more frequently than most who played in his era, between the wars. Most with any knowledge of the man have strong views about him, and not all revere him in the same way that many English cricket lovers (this reviewer included) do, but he is most certainly not the pariah that he once was.

Feelings about Jardine began to change in the early 1980s. There was a huge surge in interest in the 1932/33 ‘Bodyline’ series as its fiftieth anniversary arrived. A slew of new books were published and other media coverage, including a couple of excellent television documentaries, followed. To a new generation of cricket lovers, with the then current West Indian pace pack dominating the game, and just a few years on from the carnage inflicted on England by Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson, Harold Larwood, Douglas Jardine and their supporting cast seemed much more like heroes than villains.

At the time of his greatest triumph Jardine was certainly the most vilified man in Australia, and whilst he may have been feted on his return to England with the Ashes the aura soon tarnished. Once the full picture of what had taken place became clearer to the cricket establishment Jardine found himself and his tactics marginalised, and his resignation from the England captaincy and retirement from the First Class game soon followed.

Jardine himself wrote three books, all in the years immediately after ‘Bodyline’. The first was In Quest of the Ashes, an aloof and rather sour account of the 1932/33 series, but a fascinating one nonetheless. He then, from a position in the press box, wrote Ashes and Dust on the subject of the 1934 Ashes series. Jardine’s personality was stamped on those two books, as was his deep knowledge and understanding of the game, something reinforced by Cricket, an essentially instructional book that appeared in 1936 but which, in addition to the usual explanation of how to play the game, contained a lengthy and illuminating chapter on the subject of captaincy.

In the years leading up to his sadly early death in 1958, at the age of 57, Jardine continued to spend some of his time in the press box at major cricket matches, most notably during the 1953 Ashes series when he famously sat in stony silence next to Don Bradman. In addition one of a variety of commercial interests that Jardine had was occasional writing for newspapers, magazines and journals, but he never wrote an autobiography and, in an outpouring of grief after his death in which she destroyed much of his cricketing equipment and memorabilia, Jardine’s widow no doubt robbed future biographers of much valuable material.

Finally, in 1984, so shortly after that fiftieth anniversary, a biography did appear. Still the only cricket book written by Christopher Douglas Douglas Jardine: Spartan Cricketer is an excellent book, which in his own introduction Mark Peel describes as a sympathetic biography. Amongst his various other projects in other fields Douglas did produce an updated edition of his book in 2002, but that and a brief Irving Rosenwater monograph apart, no other writer has attempted to write a life of Jardine until now.

Despite his widow’s actions there is no shortage of material on Jardine. Literally millions of words have been written on the subject of the 1932/33 tour, both at the time and subsequently. All of the main characters have been the subject of books, and several have ventured into print on more than one occasion. But there are none of Jardine’s contemporaries alive now, which is one important area where Douglas had the advantage over Peel.

So what has emerged in recent years to prompt a second biography of Jardine? I should perhaps stress before answering my own question that for a character as important and fascinating as Jardine, who despite that remains in some ways elusive, no justification is needed for a reprise of the known facts. That said I did hope that, perhaps, some personal papers, scrapbook or other family material might have been discovered in recent years and fallen into Peel’s hands.

Sadly I have to report that nothing has emerged in the last twenty years that demands a reappraisal of Jardine’s role in the history of cricket. That is not really a disappointment however as there is no pleasure to be gained from learning that our heroes are lesser men than we thought, and if nothing dramatic has emerged Peel has his own advantages over Douglas in that he has had the full benefit of that most powerful of research tools, the internet, not to mention the contents of David Frith’s magisterial account of the 1932/33 series, Bodyline Autopsy, that was published the year after Douglas’ updated edition and which contained, inevitably, many previously unpublished insights into the character of the England captain.

Mark Peel himself is a fine writer and an experienced biographer who has already given us lives of Colin Cowdrey, Kenny Barrington, Colin Milburn and Mike Brearley, as well as other books on England’s post war tours, and on some of the games ‘ethical’ disputes including Bodyline. His reconstruction of Jardine’s life brings much fresh detail even if there are no revelations, and that part of his narrative that deals with Jardine’s cricket career contains a number of references to incidents and observations recorded by others that I do not readily recall having read before.

The one deficiency in Peel’s book is the same as in that of Douglas. Jardine is such a fascinating character that how he earned his living (as an amateur that was, of course, wholly outside of cricket) assumes rather more importance than it otherwise might. In that respect between them the two authors have discovered all that I can suspect can ever be found, and managed to establish what the sequence of events and employers was, but essentially that is far as they have been able to get.

After he left university Jardine, whose father and grandfather were lawyers, had qualified as a solicitor. What I have never been able to fathom, and it is a question I have tried without success to find the answers to myself and found all doors closed, is why Jardine did not remain in the legal profession for very long after he qualified and why, when he did, he seems to have dealt only with conveyancing and probate matters. From what we know of Jardine on the cricket field, astute, intelligent and fiercely determined, he sounds like a born litigator. Why did he not pursue his legal career? I have always wanted to know the answer to that one, but I do not now suppose that I will ever.

In terms of Peel’s general approach that, essentially, mirrors that of Douglas and using the same description that he used for his predecessor’s work, sympathetic, would certainly not be out of place. Again like Douglas Peel has chosen some excellent photographs, not all of which have been widely published before, although his book includes neither a statistical appendix nor an index. Ultimately however anyone interested in Jardine need not make a choice. There is room in any bookcase for both books and anyone with deep pockets could do a lot worse than slip a copy of Rosenwater’s monograph between them.

Leave a comment