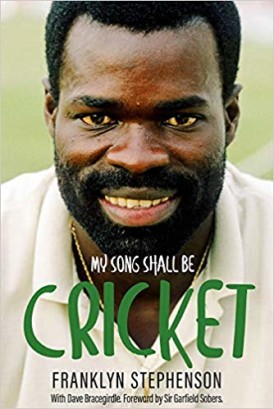

My Song Shall Be Cricket

Martin Chandler |Published: 2019

Pages: 285

Author: Stephenson, Franklyn

Publisher: Pitch

Rating: 4 stars

Franklyn Stephenson is some way from being the best known cricketer of his generation, and he makes the point in the introduction to My Song Shall Be Cricket, his autobiography, that when his name is mentioned there are generally only two reasons. The first is his trips to South Africa with the so called ‘rebel’ West Indian sides of 1982/83 and 1983/84, and the second his being the last man, back in 1988, to do the double in an English season a record which, it seems, he is likely to hold in perpetuity.

Despite being patently good enough to play the game at the highest level Stephenson never did. In fact there were only two seasons, eight years apart, in which he played any First Class cricket at home in Barbados. He spent his Northern Hemisphere summers in England playing either in the northern leagues or for one of his three counties, Gloucestershire, Nottinghamshire and Sussex. Outside England he also spent a season in the Sheffield Shield for Tasmania, and played domestic cricket in South Africa for several years in the 1990s.

Against that background Stephenson’s career is an unusual one by definition, and well worth reading more about. He also made a shrewd move in engaging the services of the Nottinghamshire based journalist and broadcaster Dave Bracegirdle to write his book. The pair no doubt know each other very well, and the result of their collaboration is an absorbing and entertaining read.

Cricketers’ autobiographies tend to rush through their author’s childhood and formative years, in most cases doubtless wisely. Stephenson however spends more time than most on his upbringing in Barbados, which is useful as it gives an insight into what shaped the character that Stephenson became. As a starting point it takes a determined and mature outlook to, as Stephenson did, leave a home in Barbados for a first stint as a professional cricketer the day before his twentieth birthday

Back in 1995 there was considerable controversy when the old Wisden Cricket Monthly published an article entitled Is It In The Blood, which questioned the loyalty of England cricketers who were not, technically, English. The article was rightly condemned and the career of Franklyn Stephenson amply demonstrates why its entire premise was wrong.

The one thing that is clear above all else from Stephenson’s story is that he was the consummate professional, always giving his all for whoever was paying him irrespective of any emotional attachment to the team concerned. I found slightly surprisingly, given the inherently insecure nature of professional cricketers’ careers, the stories of Stephenson playing through what sound like relatively serious injuries. If there is one criticism of the book it is perhaps that on the subject of those injuries Stephenson tends to describe the pain, but not go on to explain what his actual problems were, and it is not therefore entirely clear whether he risked permanent damage in playing on in the way that he did. His commitment does come shining through however, especially when pitted against his fellow professionals. The stories that involve opposing fellow West Indian speed merchant Colin Croft are particularly entertaining.

Much of the strength of Stephenson’s personality is apparent from the ‘rebel’ tours episode. He was, at only 23, a late addition to the first party due to a belief amongst those organising it that he would not be interested. As it was when the offer came in he did what he believed was best for his family, and whilst he does not express particularly trenchant views on the wider moral and political issues he clearly believes that the tours were of some assistance in moving South African politics and policies forward in a positive way.

What history does record, and which has been a subject of renewed interest in recent years, is that the lives of some of the ‘rebels’ were, effectively, destroyed by the ferocity of the negative reaction they received upon their return to the Caribbean. Others chose not to face that and left for less hostile climes. Stephenson on the other hand had the mental strength to ride out that particular storm.

Another subject that crops up from time to time in the book is Stephenson’s prowess on the golf course. A late starter at a game he seems not to have played before coming to England Stephenson’s subsequent progress suggests a prodigious talent that, had he been able to play the game in Barbados as a youngster, might well have blossomed into that of a world class golfer. As it is he has had to confine himself to playing the game largely for pleasure, albeit since his retirement from cricket he has played professionally at the renowned Sandy Lane resort on Barbados. The game is a passion Stephenson shares with his great friend, Garry Sobers, who contributes a foreword to the book.

As is always the case from this publisher My Song Shall Be Cricket is attractively presented and well illustrated. There is no index, but an extensive statistical section is present. That is somewhat unusual in that the bulk of it is two straight forward lists of the First Class and List A matches that Stephenson has played. What is lacking is a season by season breakdown of his record, and although the nature of his career is such that is not as important as it is for some, it would have been good to see the numbers from that remarkable 1988 summer recited.

It would also have been interesting, given Stephenson’s history, to have some figures from his performances in the leagues, but there is still much information that is of use and in particular the approach taken highlights the peripatetic nature of Stephenson’s career.

The story of Franklyn Stephenson is certainly different from that of most cricketers, and is a pleasure to read. My Song Shall Be Cricket is recommended.

My aunt and uncle are mentioned in this book I would like to know how to thank franklin as he remembered them and never forgot them

Comment by karen whitty | 5:26pm BST 11 October 2020