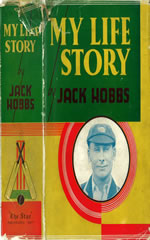

My Life Story

Martin Chandler |Published: 1935

Pages: 320

Author: Hobbs, Jack

Publisher: Star Publications

Rating: 2 stars

Between the wars Jack Hobbs was one of just a few genuine sporting superstars, and over his career around a dozen books purportedly written by him appeared. These days the professional authors who actually write such books are openly acknowledged as “collaborating” with the sporting celebrity. In Hobbs time there was no such indication of any assistance and the “ghost writers”, as they were known, toiled away anonymously in the background.

Some ghosts were better than others and Hobbs was lucky. Most of the prodigious output in his name was actually written by a journalist named Jack Ingham. In the case of Ingham a reader could be confident that the content was provided by Hobbs, and was reproduced fairly and accurately. Such displays of respect from ghost and publisher to subject were, and are, by no means universal. An example of a less satisfactory outcome for a player is Jim Laker’s Over To Me

Hobbs’ career lasted from 1905 to 1934 and there were three volumes of autobiography, published in 1924, 1931 and 1935, of which this is the last. There were also instructional books, three tour accounts, including one on the Bodyline series, and even a best selling novel, a thriller entitled The Test Match Surprise.

So what did Hobbs’ fans get for their five shillings from My Life Story ? There was certainly nothing very controversial. Hobbs always went about his business in the most dignified manner possible. That said the book would cause a sensation were it published for the first time today. On the subject of an appearance on stage as a child Hobbs, or rather Jack Ingham, writes “….. I appeared with a blackened face as a nigger boy and, holding a doll borrowed from a neighbour, I sang ‘I’se a little Alabama Coon’ “. It is difficult, in this day and age, to conceive of a more offensive action, let alone its repetition in writing. It is a vivid illustration of how times have changed – Hobbs would have been mortified at the thought of causing offence to anyone.

As the eldest of twelve children Hobbs describes an austere but happy childhood. It seems that he, like Bradman, began his cricket by hitting a ball with a stump, and that he was completely self taught – perhaps there is too much coaching today – or is the reality that Hobbs would have achieved even more had he had the benefit of modern methods?

His childhood out of the way there is a year on year account of Hobbs long career. He expresses a firm opinion occasionally, and gives praise to others from time to time, but any criticism of fellow players and administrators is mild, and his thoughts, while sound and well set out, were rarely ground breaking, and never revolutionary. By way of illustration he writes a total of just 337 words on his winter in Australia in 1932/33 – none of “Bodyline”, “Leg Theory”, “Bradman”, “Jardine” or “Larwood” figure amongst them.

Later this year Geoffrey Boycott’s biographer, Leo McKinstrey, is publishing a new biography of Hobbs. I am looking forward to reading that and am confident it will be one of the best books of the year. I plucked My Life Story from the deeper recesses of my cricket library on the basis that by reading it now I would be paving the way for a greater understanding and appreciation of McKinstrey’s work. Would I recommend anyone else to do the same? I think I will have to answer that in the negative. Make no mistake it is not an uninteresting book, but its appeal now lies largely in the lesson it gives in social rather than cricketing history. If it is a book about Jack Hobbs the man that you want to read then my advice is to wait for McKinstrey’s book, currently due for release on May 19th.

If, on the other hand, the period piece is attractive then it is not difficult to find an inexpensive copy, either of the first edition or a 1981 reprint. A jacketed first edition is trickier to obtain, but is not prohibitively expensive, but it is difficult, and costly, to acquire a copy of a limited edition of the 1981 reprint, inscribed by an 88 year old Percy Fender, and printed on art paper.

Leave a comment