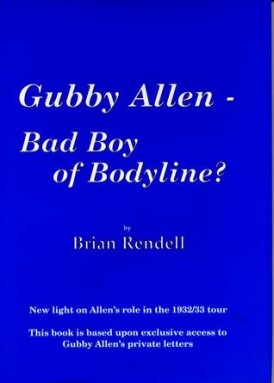

Gubby Allen – Bad Boy of Bodyline

Martin Chandler |Published: 2004

Pages: 72

Author: Rendell, Brian

Publisher: Cricket Lore

Rating: 4 stars

If there is one thing that is to blame for my becoming a cricket tragic it is ‘Bodyline’, and that fateful night in 1983 when I stumbled across that fiftieth anniversary documentary that BBC 2’s Forty Minutes put out late one mid week evening. I had always been a cricket lover, but at that time my knowledge did not stretch back beyond what my father could tell me about, so my knowledge of pre war cricket was sketchy. The Bodyline series and its leading characters captivated me immediately and, if truth be told, have never let go.

Such was the grip that the men of 1932/33 had on me was that next day, rather than go to my lectures, I went into town and bought a copy of the recently reprinted autobiography that Harold Larwood had, with the assistance of Aussie journalist Kevin Perkins, originally published in the early 1960s. Nowadays we are only a few years away from the centenary of what remains the most famous cricket tour of them all, a reminder if ever there was one that I am no longer young, and indeed am only just clinging on to middle age.

The Larwood Story was by no means the first book on the 1932/33 Ashes series, and the reprint I bought nothing like the last. Over the years interest in the series has endured and if anything grown, but what has really changed is the reputation of the architect of the controversial England tactics, skipper Douglas Jardine. In the years that followed the tour he became almost a pariah, effectively shunned by the cricketing establishment and the deeds of his side largely forgotten. That fiftieth anniversary turned the tide however, and in the twenty first century Jardine is a hero to many who were not even born when he departed this mortal coil in 1958.

If truth be told despite all the books not a great deal that was genuinely new emerged either at the time of that fiftieth anniversary or subsequently. The story and interplay between the cast of characters was and is a familiar one but some new light was shed on what happened when, in 2004, Gubby Allen – Bad Boy of Bodyline was published. Allen was the man who stood up to Jardine and refused to bowl fast leg theory, but despite that he played an important part in England’s 4-1 victory. The very embodiment of cricketing nobility Allen was the anti-Jardine, and what we know of him came, until 2004, from a gushing hagiography by that other great establishment figure, EW ‘Jim’ Swanton.

With that in mind the many who now regard Jardine as one of English cricket’s heroes will enjoy this one. The content of the book is an analysis by author Brian Rendell of Allen’s letters home during that tour, and it turns out that in actual fact Allen was, not to put too fine a point on it, a bit of a shit.

That in 1932/33 Allen refused to bowl as Jardine would have liked him to was self-evident, as is the fact that Jardine continued to select him. It is perhaps curious that, in those circumstances, Allen still felt able to field in the leg trap. He clearly didn’t like Jardine though, early in the tour writing home that sometimes I feel I should like to kill him. As for his fellow fast bowlers, Larwood and Bill Voce, they were described as swollen headed, gutless, uneducated miners – no need to sugar coat it Gubby!

Allen complained in his letters before the third Test that he never got a chance to bowl at the tail, the gentleman amateur upset that the professionals got the first chance at the rabbits in the Australian lower order (although the scorecards show he got eight wickets from numbers 8-11).He also complained of Jardine’s relationship with the Australian press writing that he asks for it with his offensive manner and is then hurt when they say nasty things about him. The first part of the comment is doubtless fair, but the latter seems deeply improbable from what we know of Jardine.

Towards the end of the tour Allen opined that there is no getting away from it Jardine is a perfect swine, before adding Plum simply hates the sight of him and so does everyone else. The views attributed to manager Warner is doubtless true, but the latter part of the comment, given the attitude demonstrated by the professionals in the party for the rest of their lives, is palpable nonsense.

And what of our hero Jardine – he must have had a lot to put up with from a man who he thought was a friend – did he turn on him? Not a bit of it – at the end of the tour Jardine wrote a letter to Allen’s father, which Rendall found was also in the correspondence. Jardine cannot have been anything other than fully aware of Allen’s antipathy to him over the preceding months, but Allen senior was still informed that his son set a truly magnificent example to the side ….. and was an excellent tourer in every way. It is crystal clear now as to who was the better man.

As Gubby Allen – Bad Boy of Bodyline is one of the books on the subject of the 1932/33 tour that has appeared in the last fifty years and actually added anything to the story it is, for that reason alone, well worth four stars. It would have been improved if there had been a few well chosen photographs, some statistics, an index and, above all, a complete transcript of the letters, but you can’t have everything. Nothing in that comment is intended to indicate other than that a copy of Brian Rendall’s first book is well worth tracking down, particularly for the many admirers of Douglas Jardine.

There’s probably scope for a good biography of Allen. It’s been done, of course, but by EW Swanton, who was a close friend of Allen’s and produced a hagiography of little value. Personally, I always wondered a bit about Allen’s sexuality – he was a lifelong bachelor, which Swanton put down to him never having met the right girl. Of course, on one level Allen’s sexuality (if indeed he had any) was his own business. But it may make him more interesting as a person, because he was a highly conservative man, strongly associated with the Establishment. If he were secretly concealing part of his life that was inconsistent with his public face, it would have been an awful strain – and would make him a more complex, interesting man. (I did once ask one of his cousins about it, who said something along the lines of “We never knew, but we always assumed”.)

Comment by Max Bonnell | 8:09am GMT 4 March 2020