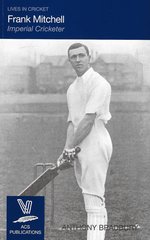

Frank Mitchell: Imperial Cricketer

Martin Chandler |Published: 2014

Pages: 136

Author: Bradbury, Anthony

Publisher: ACS

Rating: 4 stars

Having had the great pleasure of reading a significant number of the titles issued so far in the ACS Lives in Cricket series, I feel bound to say that I did not expect, on opening this one, that I would end up concluding that it is my favourite so far. It is not that it is necessarily the best written – one of Douglas Miller’s contributions would probably get that particular plaudit. Neither is subject Frank Mitchell the most talented cricketer to have been profiled – that would be Frank Foster or Tom Richardson. So why is it my favourite?

After a few days of reflection what I believe makes Anthony Bradbury’s first cricket book stand out in the way it does is that Mitchell is the perfect embodiment of the sort of cricketer who this series is designed for. He is a man who did not always lead the happiest of lives, but is a fascinating figure in many ways and his story is an ideal one for a sporting biography simply because, if it was published as fiction, it would be rightly slated as not being believable.

One of the very few Test cricketers to have been capped by two different countries, Mitchell was born in the East Riding of Yorkshire. His family were in farming, and there were clerics and lawyers amongst them, but no great wealth, thus Mitchell was one of those amateur cricketers who struggled to maintain his lifestyle. As a result he left school at 18 to become a schoolmaster, although after three years in that calling he was able to borrow the funds to enable him to go to Cambridge University where, after four years he graduated in Classics.

Whilst captain at Cambridge Mitchell was involved in what at the time was a tremendous controversy about the follow on law. During his University days he captained an England national side six times too, the other sport at which he excelled being Rugby Union, so he was a “double” international in another sense as well.

After graduating, using the many social connections he had, Mitchell was happy to accept invitations to tour North America and South Africa, the latter with Lord Hawke. This 1898/99 trip resulted in two Test caps for England, although the matches were not at the time recognised as such. Having impressed Hawke in South Africa Mitchell had a full and successful season of county cricket for Yorkshire in 1899, before he volunteered to go back to the Cape, this time to fight in the Boer War. As a result he missed the 1900 season before being back for 1901, his second and last full season for Yorkshire in which there were 1,807 runs at 44.07, including seven centuries.

A successful career with one of the strongest sides in the country beckoned, but by then pushing 30 Mitchell needed a regular income, so at this point he returned to South Africa where he made his home for the next decade or so, met and married his wife, and became a stockbroker.

There was a non-Test tour of England in 1904 which Mitchell, playing for his adopted country, was a part of, but he had no role at all in the four series that followed, three against England and one against Australia, during which South Africa established their credentials as a Test-playing nation. Thus it was a surprise when he suddenly reappeared, despite having played no “big cricket” in the meantime, as South African captain for the 1912 Triangular tournament.

After arriving in England Mitchell was served with a High Court writ issued by a Savile Row tailor seeking a sum that would today be of the order of GBP15,000, and strikingly illustrative of the “cost” of being a successful amateur cricketer at the time. Mitchell did not return to South Africa with his team, and was eventually adjudicated bankrupt over this debt the following year.

Other than a fine innings against his old county Mitchell’s 1912 season was a failure, the 39 year old being too far off the pace to make an impact, and apart from a single game in 1914 that was the end of his First Class cricket. After that he went to war again, ending up as a Lieutenant-Colonel. Returning to civilian life Mitchell became interested in the mining industry in Nigeria, and he also wrote regularly for the Cricketer. He was 63 when he died, leaving a very modest estate for his widow.

Those are the bare bones of a story that Bradbury fleshes out superbly. It must have been a tough ask with so many non-cricketing leads to follow up, and he admits there were times when he almost gave up – I am very glad he didn’t. A retired solicitor,Judge Bradbury’s legal background is clear in the way he writes. He is inquisitive, but impartial, and when points arise at which a judgment is required he sets out his own views concisely, but is at pains to point out both sides of the issue at hand, the best example being the analysis of his subject’s personality, and his rejection of another recent writer’s conclusion that Mitchell was a “racist bigot.”

Frank Mitchell: Imperial Cricketer is not quite perfect. I would have liked to know a little more about how Rugby Union was played in the 1890s, as on reading the contemporary sources that are quoted I struggled to get to grips with Mitchell’s role in a game that has clearly changed significantly. I would also like to have known more about the 1912 litigation, and particularly when the cause of action arose. But those are observations and not criticisms. Were I to describe them as the latter I am sure the kindly Judge Bradbury would give me a slightly withering look and remind me firstly that the series with which he is concerned is called neither Lives in Rugby Union, or Lives in Litigation, secondly that there are plenty of good books around on the history of the oval ball game, and thirdly that if I was really interested in how High Court cases were conducted in 1912 I could have studied English Legal History as part of my degree.

Leave a comment