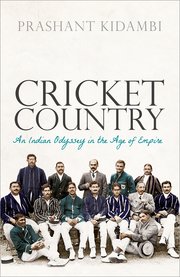

Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey In The Age Of Empire

Martin Chandler |Published: 2019

Pages: 423

Author: Kidambi, Prashant

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Rating: 4.5 stars

The visit to Britain of a team styled as All India in 1911, twenty one years before the country played its first Test match, has long been consigned to the backwaters of cricket history. The introduction to the tour in Wisden the following year explains why; the tour of the Indian cricketers was a complete disappointment. It was clear from the start that far too ambitious a programme had been arranged, and a succession of defeats destroyed any chance of public interest in the fixtures.

A look at the scorecards for the tour, none of which are reproduced in Cricket Country, suggests Wisden may have been a little harsh. The tourists did indeed start very badly, and did not record a single victory until deep in the tour. When they did however they defeated Leicestershire and Somerset in consecutive matches (the pair filled the last two places in the Championship that summer). Those were the only two First Class successes on the tour (out of 14 such matches), but no doubt buoyed by those wins the Indians went on to record victories over Lincolnshire, Durham, North of Scotland and, crossing the Irish Sea, against Ulster.

Author Prashant Kidambi is an associate professor of colonial urban history at the University of Leicester. This is significant for a number of reasons, not least of which is the research skills he therefore possesses. The work that has gone into Cricket Country is astonishing. The key to the text notes in the book’s eleven chapters runs to sixty pages, and another sixteen are taken up with a bibliography that comprises a bewildering list of sources. The downside of academia is that that world can lead to a writing style that is not designed to entertain. Those who have day to day contact with students have a better chance of avoiding that trap, and Kidambi comes nowhere near falling into it.

Cricket Country also has the benefit of being published by the Oxford University Press. There is an increasing tendency in books, no doubt at least in part due to self-publishing, for sloppy fact checking and grammar that can jar the reading experience. This is a disappointment but all things considered is, in view of the wealth and originality of new material coming onto the market, a price worth paying. But there is still a particular pleasure to be had from the experience of reading a book as well edited and produced as this one. In particular the index is a joy to behold for those of us who use them, and have become used to being grateful merely for a list of names at the end of a book.

The book was released in India a few weeks ago where, I now realise, it had a slightly different sub-title; The Untold Story of the First All-India Team. This is doubtless why my early anticipation was for a straightforward account of the cricket played by the Indians in 1911, and details of the tourists. In particular I was looking forward to learning more about the only man in the party whose reputation as a player has travelled down the years, left arm spinner Palwankar Baloo, an untouchable who was able to rise above the caste discrimination of the time.

In fact the tourists do not even arrive in England until page 190, and although the tour continues through until page 314 the narrative bears no real resemblance to the sort of account those used to reading tour books will be familiar with. Cricket Country is as concerned with events off the the field as much as those on it, and indeed the actual play is seldom the main point. It is for that reason that the absence of any scorecards or tour averages, something which I would ordinarily feel somewhat aggrieved about, is of no real significance.

So what do the first 190 pages of Cricket Country concern? First of all, for the uninitiated such as this reviewer, there is an explanation of who the Parsis were and are, their role in the development of Indian cricket and the efforts gone to to establish the game in Bombay and beyond. The route to the 1911 trip taking place was a long road and it was a considerable achievement, in a country where cricket teams split very much down religious lines, for a side that fully justified that ‘All India’ tag to be put together; there were representatives drawn from the Hindu, Muslim and Parsi communities as well as a solitary Sikh in the touring party.

Back in 1911 there was one Indian cricketer who was revered throughout the cricket playing world, Ranji. In 1911 Ranji was 39. He had not played for England since 1902 and the English summer of 1908 apart had been in India. He was not, of course, the player he had once been but was still good enough to come back to England for one last hurrah in 1912 and make more than 1,000 runs for Sussex. Ranji would certainly have improved the playing standards of the 1911 party, and added immeasurably to their appeal, but he could not be persuaded to throw in his lot with his countrymen.

Ranji is a fascinating character who has been the subject of a number of biographies. In 1934, a year after his death, what amounted to an authorised biography appeared from the pen of Roland Wild. It portrayed Ranji as he would have wished, both as cricketer and as a statesman. The truth however was rather different and first Alan Ross, and later Simon Wilde have published biographies that stripped away the carefully constructed outer layers of the legend and discovered the much less admirable aspects of Ranji’s character that lay beneath. That part of Cricket Country that deals with Ranji is Kidambi at his best.

As is only to be expected from a ‘proper’ historian Kidambi uses his closing chapters to draw together his conclusions and put his research in its proper context. Cricket Country goes well beyond the usual parameters of cricket writing, and while it certainly won’t appeal to those whose interest in Indian cricket does not stretch far beyond the IPL, for those who are interested in where the Indian game has come from it really is a ‘must read’.

Probably the most thoughtful review of this excellent book I’ve read yet.

Comment by Dan Weisselberg | 3:48pm GMT 12 March 2020