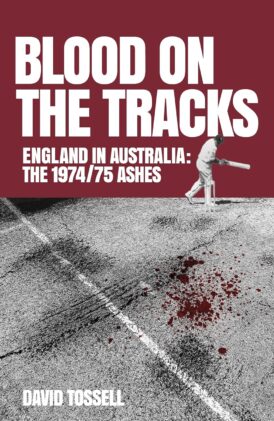

Blood on the Tracks

Martin Chandler |Published: 2024

Pages: 386

Author: Tossell, David

Publisher: Fairfield Books

Rating: 5 stars

I will declare an interest immediately here, that being that I have been eagerly awaiting this one ever since I first learned it was being written, which must be two or three years ago now. The reason is simple enough. I recall the Ashes series of 1968 and 1970/71, but the first one I really ‘lived through’ was 1972, when Ian Chappell’s Australians won at the Oval to level things up at 2-2. That of course meant that Ray Illingworth’s side retained the urn they had taken back in Australia 18 months previously.

By the time of England’s next visit to Australia, in 1974/75, Illingworth was gone, and England were captained by a Scot, Mike Denness. From a personal point of view I had by now completely fallen under the game’s spell, had my own radio that I was allowed to keep in my bedroom and had secured my parents’ agreement to being able to set an alarm and turn it on each morning to listen to the commentary. Later on, in our evening, there was a full highlights package available on BBC2.

And if the result of the series, a crunching 4-1 win to Australia, was disappointing the contest was not as the man with the broken back, Dennis Lillee, and the man no one in England had heard of or seen coming, Jeff Thomson, produced between them as stunning a display of fast and hostile bowling as I have ever seen.

The footage we saw means the series is seared into the memory. The newspapers were full of reports, comment and opinion. Slightly surprisingly there were only two accounts of the tour in book form, one published here by Christopher Martin-Jenkins, and the other by Frank Tyson in Australia. But in addition to that at some point in the last half century almost all of the major players have either gone into print or been the subject of biographies.

David Tossell, a man whose previous writings have deservedly earned him numerous awards, is a man who knows how to recreate a past Test series, his atmospheric account of the 1976 series between England and West Indies, Grovel!, being one of the very best of the genre. Sadly not all of the men involved in 1974/75 are still with us, but many are and their memories together with the fact that, like me, Tossell ‘was there’ add authority to the narrative.

So in truth Tossell was shooting at open goal with this project but, as even the best strikers will tell you, it is still possible to miss one of those. There is no disappointment with Blood on the Tracks however, as the book is right up there with the very best of its kind, or indeed any kind.

Half a century on, before opening the book, it was only the on field events of 1974/75 that stuck in my memory. But reading this fullest of accounts immediately transported me back in time, and reminded me of the selection dilemmas that faced the selectors. They wanted their best batsman, Geoffrey Boycott, but ultimately he declined their invitation. On the other hand they didn’t want their best fast bowler, John Snow, although he would have been prepared to travel.

The touring experience has certainly changed over half a century. Unlike today there was no entourage with the tourists, who were accompanied by manager Alec Bedser, his assistant Alan Smith and physio Bernard Thomas. Also quite unlike the modern tour there were as many as nine games scheduled prior to the first Test, Four were First Class fixtures against South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, and the others a relatively undemanding series of ‘up country’ games.

The early part of the tour was not without its problems for England, mainly related to injuries. But they went into the first Test unbeaten, and with victories over Queensland and New South Wales. The first day of the first Test, Australia having won the toss and chosen to bat was relatively uneventful. Tossell’s writing style is ideally suited to this sort of account. He steers the narrative, but much of it consists of the observations of those involved, some contemporary, and some with the benefit of hindsight. As a means of describing a cricket match the benefits of Tossell’s approach are vividly demonstrated as the England first innings begins, and Lillee and Thomson are unleashed, and the tempo changes completely.

But Blood on the Tracks is not solely concerned with events on the field. The digression around Colin Cowdrey’s call up after the first Test is a particularly good one, and there is one remark of the old stager’s that particularly struck me, that being his reference to it taking at least three weeks to get used to Australian conditions. This one being his sixth Ashes trip no one could speak on that subject with more authority than Cowdrey, and it is a clear indication to me that England will, given the scheduling of the third decade of the 21st century, in all probability never win an away Ashes series again.

Another issue that intrigued me was the question of wives and children accompanying the tourists. I did recall that the wives were invited, but had not realised that they were limited to 21 nights with their husbands, and that their physio had the unenviable task of keeping the necessary records. That was a surprising revelation, but genuinely shocking was that the players had to pay their families’ way to get them to Australia. On that theme the fact that Denness was expected to pay some private medical expenses himself also struck me as quite extraordinary.

The entire story is, of course, one of English defeat, but the Australians contribute their share of the many insights Blood on the Tracks provides, and such troubles as they had are certainly not ignored, one excellent chapter telling the story of Ian Chappell’s constant battle to improve the remuneration the Australian players received which, in these pre World Series Cricket days, verged on the derisory.

The Australians regained the Ashes when they took an unassailable 3-0 lead after winning the fourth Test. At that point Tossell pauses to take a look at the then contemporary attitude of Australians towards the ‘mother country’. It is not a lengthy treatise by any means but, as a consideration that I must admit had not crossed my consciousness at the time, does shed much light on what proves to be an interesting and relevant consideration.

After that the Australians handed out another chastening experience to England in the fifth Test before, Thomson out injured and Lillee breaking down after just six overs England, with major contributions from the previously ineffective Denness and Keith Fletcher, well supported by John Edrich and Tony Greig with the bat and Peter Lever with the ball, coasted to an innings victory, and then it was all over?

Not quite, because this was to be the last Ashes tour which, tagged on to the end, saw a tired and homesick England team visiting New Zealand for, on this occasion, two Tests. If it had been a surprise that no one had had been seriously injured in Australia the first of those two Tests was the one in which, struck on the head by a bouncer from Lever, Ewen Chatfield might well have been a fatality without the intervention of England physio Thomas.

And then it was home for the inquest, something I remember well, although not having access to the Daily Mirror in those days I hadn’t read Peter Laker’s description of the tour as the greatest English cricketing disaster since the squires of Broadhalfpenny Down invented the game, and his description of the team as an apathetic bunch who have theorised themselves silly off the field and performed like clowns in the middle.

The blame was laid everywhere, schools cricket, coaching, the limited overs game, overseas players in and the structure of the county game being the favoured hobby horses. I have to say though that my thought at the time was that the honourable members of the fourth estate were a bunch of idiots, although I understand now that their priority was to sell newspapers and not necessarily to write what they really thought.

The truth as I saw it then, and still see it now, was clearly evidenced by the events that unfolded in that final Test. For ten weeks between the end of November 1974 and the start of February 1975 two great fast bowlers were at the absolute peak of their powers, and Blood on the Tracks is a superb tribute to them, and to everyone else who contributed to that remarkable southern hemisphere summer.

The book itself is very well designed and set out, with a good selection of photographs as well as all the scorecards and tour averages. In addition there are detailed score sheets for each of the six Tests to delight the statistically minded and, of course there is the borrowing of the title of one of Bob Dylan’s finest albums. Only in one respect does Blood on the Tracks fall short of perfection. By my arithmetic seventeen of the men who appeared in the series, seven Englishmen and ten Australians, are still with us and a specially bound limited edition signed by all of them would be the ultimate ‘must have’ item for the bibliophiles amongst us.

It was Cowdrey’s sixth Ashes trip, not his fifth.

Comment by AndrewB | 12:00am GMT 18 November 2024