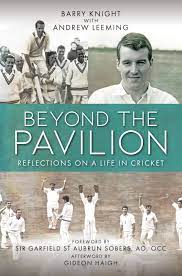

Beyond The Pavilion

Martin Chandler |Published: 2022

Pages: 255

Author: Knight, Barry and Leeming, Andrew

Publisher: Quiller

Rating: 4 stars

The view of Trevor Bailey, who was a colossus of Essex cricket throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, was that Barry Knight was one of only three cricketers who, after a brief initial look, he was convinced would play international cricket (the other two were Keith Fletcher and West Indian Keith Boyce).

As an all-rounder it would be fair to say that ultimately Knight did not quite scale the heights that Bailey thought he might. He did play for England in 29 Tests, but was never sure of his place, his longest run in the side being one of six matches. A right arm seam bowler Knight was not genuinely fast but at his best was certainly sharp and given a green wicket was able to obtain plenty of lateral movement. With the bat, at a time when such were rare, he was a stylish and free scoring batsman, albeit one who it is said was not particularly comfortable against fast bowling.

But there was rather more to Knight than just being an archetypal English cricketer. He played his final First Class match in 1969 at just 31 and went to live in Australia where he has remained ever since, playing Grade cricket and becoming a much vaunted coach.

Another great talent that Knight has is asa raconteur, and although co-author Andrew Leeming has only one previous book to his credit he has done a terrific job of presenting Knight’s stories and opinions in Behind the Pavilion.

Knight played the game in interesting times. When his career began the old division between Gentlemen and Players still dominated the English game. But he saw that disintegrate and, very much a Player himself, he enjoyed a positive relationship with Kerry Packer and watched from close at hand as the World Series Cricket revolution unfolded.

Of those 29 Tests the majority were played overseas, on two tours of the sub-continent and two Australian Ashes trips. A sociable man many well worn stories concerning the great players that Knight played with and against are told, as well as some new ones. In particular the story of a fist fight between Bill Edrich and Fred Trueman in Australia in 1962/63 was one I had never heard before, and which is not even hinted at in the last of Trueman’s four autobiographies nor in Chris Waters’ 2012 biography.

As any reader would expect much of Beyond The Pavilion contains Knight’s reflections on those he played with and he rightly takes pride in one record he holds, that of the bowler who has dismissed Garry Sobers in the highest percentage of their Test encounters, a figure for him as high as 50%. To put that in context there were only four Tests involved, and Sobers scored plenty of runs as well. But Sobers was a true great, and any bowler who claims his wicket four times has every right to be proud of that achievement. Knight also counts Sobers as a close friend, and the great all-rounder provides a characteristically warm foreword to the book.

But Knight can tell a story against himself as well, one of the best involving Geoffrey Boycott. Knight relates how on one occasion, having watched him amass a typically painstaking Test century, how he later enquired of Yorkshire’s finest; Don’t you get bored out there playing like that? I do hope the rest of the tale is not apocryphal, Sir Geoffrey’s quoted response being; No, not at all, because out there I don’t have to talk to idiots like you, do I?*

Having played a bit part in the drama as it unfolded Knight also dwells at some length on Basil D’Oliveira and the huge controversy in 1968 that bears his name. There is something about a good row that seems to attract Knight, given much of the latter part of the book relates to his work with Kerry Packer and his son James.

So how do I rate this one? It is a tricky question because so enthused was I that, had I not first opened the book at nine o’clock in the evening on a weekday, I would probably have read it through in one sitting, something which is the acid test of a five star book. The only problem is that having finished the book, despite the great pleasure I got from reading it, I was still left disappointed.

There is no doubt that Beyond The Pavilion is autobiographical, and there is a good deal of detail about Knight’s early and development as a cricketer. But it is not an autobiography in the fullest sense of the word, and therein lies the cause of my disappointment.

Barry Knight in the 1960s was a fascinating character. By all accounts he moved in some interesting circles and knew many celebrities, and not always those with the best of reputations. Knight also had ambitions beyond playing professional cricket, opening several men’s fashion shops including, finally, one in the Chelsea of the ‘Swinging Sixties’. Quite what happened I don’t know, because Knight doesn’t deal with the subject at all, but ultimately he bit off more than he could chew with that and the business failed, as did his first marriage.

The situation got so bad for Knight that, during that 1968 summer of an Ashes series and the D’Oliveira Affair coming to its head, his story appeared in the country’s leading national tabloid Sunday newspaper, the old News of the World. The headline was Why I tried suicide – by Test star Barry Knight. The exclusive disclosed the failure of Knight’s business and marriage as the major causes of his despair.

And it isn’t just the more salacious stories that are missing. There is very little mention in Beyond The Pavilion of the reasons for Knight leaving Essex and joining Leicestershire in 1966, nor any word of what must have been a fascinating episode when Knight and Essex, both heavily lawyered up, faced off before the MCC committee tasked with settling disputes about qualification periods. Knight seems to have been partially successful, in that he missed only the 1967 – there must be quite a story to be told there.

Similarly a couple of years later, still with two years to run on his Leicestershire contract Knight decided, late in the day, not to return to the county from his winter work in Australia for the 1970 summer thus bringing down the curtain on a career which, just the previous season, had seen him playing in five of the summer’s six Tests. There must be a tale or two there as well, and not just the one involving what became of Knight’s car.

Choosing not to relive what are no doubt painful memories is perhaps understandable, albeit disappointing. Less easy to figure out is the lack of detail about the origins of the Australian coaching business. There is some material on the subject, and the name of Allan Border looms large, but my understanding is that Knight’s contributions to the dominant Australian sides of the latter years of the twentieth century went well beyond Border.

So only four stars for Beyond The Pavilion, but only because it doesn’t tell the full story, and the part it does tell is brilliantly done – let’s hope there might be a follow up, and if so that one will certainly be a candidate for a five star review.

*I am delighted to be able to report that Sir Geoffrey took the trouble to respond to my enquiry about this episode, and he confirmed there is nothing amiss with Knight’s memory.

Just read this one, and I have to say I found it disappointing. Part of this was the structure: it starts as a conventional memoir, but then jumps all over the place, without warning and without any apparent structure. One minute Barry is paying his dues at East Ham school and being scouted by Trevor Bailey, then he’s in India with the MCC team, with no hint at how he got from one place to the other. That’s OK, but the episodes are so disjointed it’s distracting. A whole chapter is devoted to a hackneyed Fred Trueman anecdote about a game in which Knight never played. There are odd repetitions – we are told several times that Frank Rist kept wicket when Essex played Australia in 1948 (once would have been plenty). But what really spoiled it for me was the sheer number of factual errors, that might easily have been checked. Knight did not play “only one Test” under Peter May’s captaincy – the actual number was zero. There is no team called “Australian Combined Schools” – the team James Packer played for was the “Combined Associated Schools”. It is simply not true that, in the 1950s, it was common for county teams to play “schoolboys” during the holidays – that happened, but it was rare, and the example given in the book is Charles Williams of Essex, who was 21 (and three years out of school) when he first played for Essex. I hate to be a pedant, but does no-one check facts anymore?

I should add that I attended the Barry Knight coaching school for a week when I was 14. He wrote a report on each player at the end of the week. His analysis of my technical flaws with bat and ball was brilliant, absolutely spot-on. Unfortunately, he never got around to telling me how to fix them! I suppose you needed to go back for a second week for that.

Comment by Max Bonnell | 4:26pm BST 18 September 2023