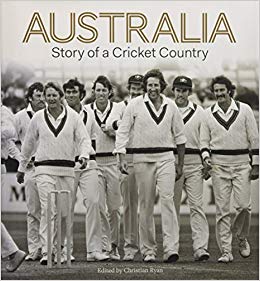

Australia: Story of a Cricket Country

Jon Gemmell |Published: 2011

Pages: 400

Author: Ryan, Christian (Editor)

Publisher: Hardie Grant

Rating: 4.5 stars

To compare this book to the quarterly journal The Nightwatchman is the greatest compliment I can make. Its 38 articles range from the playing of cricket in conflict zones, the niceties of off-spin bowling and obsessing on Gary Sobers and Alan Turner (to name just two), to a history of scorekeeping, pitch curating and pencil cricket. It also includes works of sociological analysis and a moving piece by Cass Francis who finally went to his first Test match, at the age of 89. What puts this book into a different league, though, is the stunning accompaniment of photographs.

There are a number of articles that dwell on the heroic characteristics of favourite players. Doug Walters, for example, is described as the first ‘sixties’ cricketer to reach the Test team; a man whose legendary value is built on the pleasurable consumption of cigarettes and beer. Of course, any history book on Australian cricket will examine the role of Don Bradman. To some he is ‘a selfish, divisive person who fought advancement.’ Mark Mordue notes that hard-core Catholics and Labor voters could not support the Anglican-conservative. Australia’s heroes are working class and Bradman was never really a man of the people. Yet, when it came to a poll of past Test cricketers on the greatest Australian player, the Don inevitably came top. He represented a very young Australia still in search of an identity; a country that had no war of independence and lacked towering figures around which to rally.

Shane Warne, Dennis Lillee, Adam Gilchrist and Keith Miller make up the top five and there are warm tributes to each. Mike Brearley remembers how Lillee got all of the England and Australia players to sign his infamous aluminium bat, and then years later gave it to the Englishman’s son. Gilchrist’s ordinariness is described as what makes him so out of the ordinary.

The articles on the social history of cricket help us better understand how the sport has evolved. At the top level it started as a very middle-class pursuit. Of the 1878 tourists to England, for instance, three worked as bankers, five as government employees, two worked for the courts and only one, Charles Bannerman, was a professional cricketer. W.G. Grace praised Victor Trumper for his fielding, adding, ‘but I’m afraid to say batting is not your forte.’ Both would have their obituaries in the 1916 Wisden. Trumper left a wife and two children aged nine and eighteen months, alongside an estate valued at just £5. Up until World War II there were very few Australian cricketers from working class backgrounds. The standard working week of 48 hours spread over six days, with no annual holiday entitlement, left little time to play recreational sport.

Sean Gorman bemoans a total absence of the written word of Aboriginal players’ thoughts or feelings about their 1868 tour. ‘All that remains is a vast aching silence.’ Bernhard Whimpress reminds us, ‘that at a time when Aboriginal heads were being collected in European museums, the cricketers must have seemed something like living museum pieces.’ Cricket’s rituals, language and customs were imported from England. To indigenous Australians they represented a conversation that they are not part of. When asked by Justin Langer whether they followed the Aussie Test team, several Aboriginal cricketers responded that they preferred to support sides like the West Indies, Pakistan and India instead.

Rahul Bhattacharya notes that when John Wright became Indian coach, he informed his players that to beat Australia, you have to be Australia. ‘You don’t look up to them … you fucking look down on them.’ He later compares the two sides as one superculture in ascent verses one in descent. Indians can change umpires, threaten tours and even change constitutions. ‘We can do more than merely defeat them: we can own them.’

My favourite essay was Nathan Hollier’s delve into cricket biographies to provide insight into past Aussie attitudes. The teams the Chappells led in the 1970s were known to be culturally crass, fixated on winning and less inclined to care for the game’s finest traditions. The ‘ugly’ Australians saw themselves as workers not gentlemen, professionals not amateurs. There’s was a class consciousness, pro-Australian with an anti-English sentiment. They believed in a fair-days’ pay for a fair-days’ work. Rodney Marsh noted in Gloves, Sweat and Tears: ‘we had one thing in mind, and that was to win … We disagreed violently with the old homily that how you played the game was the important thing.’ Professor Ian Lowe notes in the concluding article that little has changed; of how in Test, state and grade cricket, winning comes close to being the sole aim. Sharp practice, sledging and gamesmanship are all justified by the need to win.

This is a something-for-everyone collection, with my only gripe being the formatting in the last third of the book. I read it on a kindle and the formatting looks like it was completed by someone challenging the record for number of tins of lager drunk on a flight to England. So, lose half a star, but don’t let that put you off what is a wonderful volume.

An outstanding book, featuring a collection of exceptional essays alongside some wonderfully evocative photographs (my favourite perhaps being that of Mick Jagger at the 1972 Ashes test at the Oval, walking along beer in hand as just one of the crowd). I am though puzzled by your complaint about the formatting of the final third of the book. Perhaps this is something to do with reading it on a kindle – I can’t see anything amiss with my copy of the book.

Comment by John Perry | 10:27pm GMT 8 February 2020