The Naenae Express

Martin Chandler |

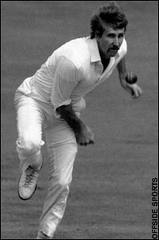

England had a miserable time in Australia in 1974/75, Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson striking terror into the hearts of most of their batsmen, and the home side took a 4-0 lead in the series before, with Thomson unfit to take the field and Lillee breaking down after just six overs, England comfortably won the dead rubber at the MCG thanks to Peter Lever taking four quick wickets at the start of the Australian first innings. Lever ended up with a match haul of 9-103, and a couple of big scores from Mike Denness and Keith Fletcher ensured England put more than enough runs on the board.

Earlier in the series Lever had played in just the first Test at the ‘Gabba, going wicketless in a 166 run defeat. His success in the final Test was a major turn-up for the book, as his tour had been a poor one, his other 15 First Class wickets costing him nearly 43 runs each. Lever celebrated his 34th birthday before the series began, so was perhaps a little past his best. He had enjoyed some success in Australia with the victorious side captained by Ray Illingworth four years earlier, but he had never been an England regular. He was a good bowler at county level, but wasn’t quite quick enough in the Test arena, being an honest fast-medium rather than genuinely fast.

Buoyed by their win in the final Test England travelled to the Shaky Isles, as they always did in those days, for a couple of Tests against rather more modest opposition than they had met in Australia. The first Test was at Eden Park and England spent the first two days, Denness and Fletcher once again to the fore, compiling a massive 593-6. Debutant Ewen Chatfield, first change after a young Richard Hadlee and the veteran Dick Collinge took the new ball, ended up with 0-95. New Zealand fought hard over the next two days, but as the fourth day’s entertainment concluded they were in a hopeless position, still needing another 106 to make England bat again, with their last pair at the crease. All that stood between England and victory were another debutant, Geoff Howarth, and Chatfield. Dismissed after five deliveries for a duck in his first innings, this was Chatfield’s twelfth First Class match, and he had yet to score more than 5.

Despite his limitations Chatfield had done a decent job with Howarth late on the fourth day, hanging around for almost an hour and defying everything that the England bowlers could throw at him. He ended the day with 4 runs to his name. On the final morning he carried on the good work, assisted by Howarth making a decent fist of farming the strike. Lever, whose form in the match had been rather more ‘Gabba than MCG, would have been getting frustrated with Chatfield, particularly after he induced, with a short ball, a hurried prod that only just eluded a close-in fielder.

As the morning wore on the home side’s position ceased to be completely hopeless, as there was a large and angry looking cloud to the west of the ground, and a blustery wind was moving it towards the play. Chatfield was looking fairly comfortable, and with Howarth adept at pinching the singles he needed to keep most of the strike, the weather saving the New Zealanders became a real possibility. After 45 minutes play Lever sensed an opening – he unexpectedly found himself with four deliveries to bowl at Chatfield. Eight ball overs were the order of the day in New Zealand at that time, and the tension had got to Howarth, who had miscounted. It was going to be the Lancashire man’s final over, and remembering the false shot that his last short one induced he moved a couple more fielders around the wicket and dug the ball in. When Chatfield saw the length he tried to get behind the ball. The ball hit either his glove or the bat handle, but from there it deflected on to his head. Perhaps surprisingly Chatfield did not go down immediately. He later recalled feeling dizzy, walking over to the side of the pitch and kneeling down.

It was fortunate indeed that those close fielders were there, as it meant that the moment Chatfield’s breathing became fitful and he started frothing at the mouth the England players were on hand and knew something was seriously wrong. The biggest problem was that, in light of the anticipated early finish, the New Zealand Cricket Council had not arranged for a doctor to be present. England’s physio, Bernard Thomas, didn’t know that, and as the fielders waved frantically in his direction he hesitated, not wanting to step on anyone’s toes.

After a few moments the hint of panic in John Edrich’s voice won the day and Thomas ran out to the middle. It was as well that he did as by now Chatfield’s lips were turning blue, and he was barely breathing. Thomas instantly knew that the airways were blocked by Chatfield’s tongue. He was assisted by a first-aider who had come on to the ground, but their joint effort failed. Thomas told the other man to arrange a stretcher and an ambulance, and went back to his attempt to revive Chatfield, whose heart had by now stopped beating. At this point there were only minutes before irrepairable brain damage set in and, having been told that there was no resuscitation equipment on the ground, Thomas feared the worst.

In fact, despite the first-aider’s belief it turned out there was some resuscitation equipment available, and Chatfield briefly came to in the ambulance before lapsing into a rather more comfortable unconsciousness. His conversation in the ambulance showed he was clearly aware of the match situation and that, unbeaten on 13, he had reached his highest First Class score. Once he arrived at hospital Chatfield was x-rayed, and a 1.5 inch fracture found just below his temple but the real worry, that a nearby artery was damaged, proved a false alarm, and he was discharged from hospital two days later.

The game was televised, so the New Zealand public saw the drama unfold even if they weren’t aware of just how dangerous the situation was. Lever was distraught, and Chatfield said later that when he visited him in hospital the same afternoon the England bowler looked infinitely worse than Chatfield felt. The incident was of course widely reported, but Thomas played his cards close to his chest, and it was not until more than a decade later when he spoke to Lynn McConnell, who was “assisting” Chatfield with an autobiography, that he spelt out that to all intents and purposes Chatfield had died at the crease on 25 February 1975.

Despite the injury Chatfield was fit for the beginning of the next domestic season, and the following February he resumed his international career against Australia in New Zealand before, a year later, he locked horns with England once again, and ran into a different kind of controversy. He was twelfth man for the first Test, his country’s first win against England in 48 attempts over 48 years, but an injury to Dayle Hadlee meant that he was included for the second Test. After taking a first innings lead of 183 England were desperate for quick runs at the end of the fourth day in order to get New Zealand back in. The visitors were 47-1 when Chatfield “mankaded” Derek Randall. The cause of the resulting furore was that Randall was said not to have been warned. Wisden was not amused, and the match report was deeply critical of Chatfield’s action.

For his own part Chatfield believes that an appropriate warning was given. He had, a delivery or two beforehand, instructed his mid-off, twelfth man Bruce Edgar, to “keep an eye” on Randall, a comment that if not shouted at Edgar was certainly, given that the fielder got the message, said with sufficient volume for Randall to be alerted to the fact that he had been rumbled. In fact it may well be the case that the eccentric Randall, concentrating on his batting rather than what the New Zealanders were saying to each other, did not pick up what was said, but given Mark Burgess did not call Randall back, the skipper was presumably as aware of what had been said as Edgar.

England went on to win the game, and at the time Chatfield felt, with some justification, that he had not received the support from his teammates and management that he deserved. The game is remembered to this day for a run out, although Chatfield’s error of judgment, if that is what it was, is not the one. Randall was replaced at the crease by a 22 year old Ian Botham, who deliberately ran out his captain, Geoffrey Boycott, three overs later, and that is the tale that has stood the test of time. For Chatfield there was no place in the side for the final Test, and his omission from the party that toured England in 1978 must surely have been linked to the “Randall incident”.

Chatfield spent the next three years in the international wilderness despite some impressive performances. In 1979/80 for example he took 49 wickets at 10.81. The great West Indies side was in New Zealand. Chatfield didn’t make the Test side, a decision all the more remarkable when his performance against the tourists for Wellington, a game played between the first and second Tests, is taken into account. Wellington humbled their guests by six wickets. In a low scoring game Chatfield’s match figures were 13-86, the best of his career.

What sort of a bowler was Chatfield? His most illustrious strike partner in Test cricket was inevitably Sir Richard Hadlee, who described him as surely the most consistent line and length bowler in top level cricket ….. whenever he has shared opening duties with me, he has been the ideal foil. He bowled tightly and gave so little away that I was free to attack. Howarth, New Zealand skipper when Chatfield finally got a regular gig, wrote many years later With Chatfield, what you saw was what you got. Quiet, straight up and down, dependable on and off the field, and a thoroughly nice guy. He was the unsung hero of the Hadlee era and did not get the kudos he deserved. It was a reputation that followed him throughout his career.

In March 1983 Chatfield got back into the Test side against Sri Lanka, and for the next six years he was either Hadlee’s opening partner or first change, missing only a handful of Tests. He performed his appointed task with unflagging enthusiasm, bowling like a metronome for long spells, rarely producing a bad ball, and always ready to pounce on an unwary batsman. As befitted a man who eschewed the spectacular there were no memorable matchwinning performances with the ball, but there was one heroic display with the bat that took his side to victory against Pakistan in February 1985.

In November and December of 1984 Pakistan had beaten New Zealand at home, 2-0 in a three Test series. There was to be a rematch in New Zealand in the opening weeks of 1985. The hosts were in a good position in the first Test before rain washed out the final day, but won the second by an innings. The final match was played at the windy and chilly Carisbrook Oval in Dunedin. New Zealand, well able to make the best of a wicket that, as befitted the ground’s normal use as a Rugby stadium, was by no means the flattest in the world, started the Test confident of their ability to reverse the 2-0 margin of earlier in the season. They reckoned however without the prodigious talents of an 18 year old left arm pace bowler playing in just his second Test. In the innings defeat at Eden Park in Auckland Wasim Akram had looked no more than promising in taking 2-105, but at Dunedin he showed he was already the finished article, taking five wickets in each innings to leave the home side on 220-8, still 51 short of victory. Lance Cairns had earlier been hit on the head by an Akram bouncer. Unlike Chatfield a decade earlier the big man had been able to get himself back to the pavilion, but like Chatfield it was later revealed that he had fractured his skull. Cairns being Cairns he expressed himself to be ready, willing and able to go back in at the fall of the ninth wicket, but Chatfield knew from his appearance, as did the rest of the side, that that couldn’t be allowed to happen.

New Zealand had never scored as many as 278 to win a Test before, and Chatfield certainly wasn’t expecting this to be the first time, but as Peter Lever and England had learned he was stubborn and courageous, two very useful qualities in such a situation.

The Pakistanis did not help their own cause by rubbing Chatfield up the wrong way. His partner was future skipper Jeremy Coney, whose batting might not be quite as peerless as his commentary is these days, but he was a decent player nonetheless. But the Pakistanis weren’t interested in Coney, who they were happy to give a single to whenever he got on strike. In fact Chatfield found batting relatively straightforward, and his confidence grew. According to Coney he had a unique approach in that he played for the edge of the bat, a habit that was hugely frustrating for bowlers. In Chatfield’s autobiography Coney’s views on his batting are put in a wholly matter of fact context – a quarter of a century on and Coney’s impish humour is known to all, and in retrospect one suspects his tongue was firmly planted in his cheek when he spoke to McConnell.

Whatever Chatfield’s technique of choice was he began to take a few singles of his own, and at tea the sides went in with New Zealand half way there, with 25 runs to go. The impossible was now very much on, and Chatfield admits to being so nervous during the interval that he could not even drink his tea without spilling most of it on the floor – eating was out of the question.

A crucial moment came just after play resumed when the Pakistan wicketkeeper, Anil Dalpat, the first Hindu to be capped for them, dropped Coney. That did nothing to ease the tension for Chatfield and for a time he looked rather less secure than he had before tea. Feelings amongst the Pakistanis started to run higher as well as umpire Fred Goodall warned Akram for bumping Chatfield. From his own point of view Chatfield would claim never to have bowled a bouncer in his life, adding wistfully that he wasn’t quick enough, but his sympathies lay with Akram. He accepted that in that situation, and hanging around as he had, that he was entitled to expect some short stuff. He was also, ten years on from his brush with death, much better protected.

Inching towards the target was shredding the nerves of all and it was a major boost for both batsmen when Chatfield finally got a delivery well up on his legs that he was able to steer through the infield, from where it ran gently to the unguarded mid-wicket boundary. Suddenly the target was down to single figures, and breathing was a little easier. It was the only four in the entire partnership, and there were only two other scoring shots that weren’t singles. The second of them, a couple from a paddle round the corner by Coney from the bowling of the bustling Tahir Naqqash, brought up a famous victory.

Chatfield rightly regarded the match as the highlight of his career, given that he won a game by doing something it was not his job to do, and that he would never have been expected to achieve. Perversely in many ways his role in that partnership of 50 was that of senior man. He contributed almost half the runs, 21, but more significantly of the 132 deliveries it took he faced 84 to Coney’s 48. Even Wisden commented on the intensity of the atmosphere at the ground, and summed up the guts that Chatfield displayed by commenting that his runs were almost outnumbered by his bruises.

The mark of a true batting rabbit is often said to be a cricketer who has taken a greater number of First Class wickets than he has scored runs. Chris Martin is probably the best known recent example, but it is a high bar, as reflected by the fact that Monty Panesar, not noted for his skill with the willow, has scored more than twice as many runs as he has taken wickets. Chatfield though is in that exclusive club, a remarkable achievement for a man whose greatest day came with the bat, and who had displayed his durability on several other occasions, notably that dark day in 1975.

A couple of months on from Dunedin and Chatfield, by now pushing 35, enjoyed his best Test with the ball as well. He chose strong opposition too, Viv Richards’ West Indies at the Queen’s Park Oval in Port of Spain. In a drawn match Chatfield, who was suffering from a heavy cold, took 4-51 and 6-73. He might have been forgiven for expecting the occasional superlative, but it wasn’t to be.Wisden described his bowling as steady, and his match figures as just reward for his consistency, and every other unbiased report was worded in much the same way. Simon Hughes, a not too dissimilar bowler, had summed him up rather well in The Cricketer after the Pakistan series when he wrote; The methodical Ewen Chatfield epitomises the New Zealander. Farmer-like in appearance yet always unruffled, he is their Mr Reliable, seemingly incapable of delivering a half-volley.

Chatfield bowled on for New Zealand until well into his 39th year, and his final Test was at Eden Park in February 1989 against Pakistan. As a result of the actions of the groundstaff there wasn’t a blade of grass on the wicket, which was moribund in nature throughout the match, and a highscoring and tedious draw ensued. Pakistan scored 616-5 in their only visit to the crease. Chatfield’s figures were an unflattering 1-158, but he was never collared, running in for 65 overs. He played a couple of times for Wellington in December 1989, but then decided to call time on his First Class career and, deservedly, his name found its way into the New Year Honours List for 1990.

Ewen Chatfield MBE is now 63 and still plays club cricket on Saturdays. He is as accurate a bowler as ever, and to this day bats at number eleven. He has never had any desire, as so many of his former teammates and opponents did, to work in the media, and although he is often to be found as a guest at international matches, mixing happily and effortlessly with all and sundry, he is content to earn a living driving a cab around Wellington.

You should have picked up the phone to the Naenae Cricket Club and asked for an interview. He’s definitely one of those stalwart club cricket legends – just one of the very few that made it to the top table.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am BST 29 April 2014

Great article again Fred but I have to stick up for Peter Lever. Always thought him a fine bowler and very important to Illingworth’s successful team. I suspect he was a bit more slippery than the fast medium he is often classified. You have to have some serious heat to injure a player like he did Chatfield. Kerry O’Keefe, a competent defensive player, describes the pain being hit by Lever and saying he checked for the exit wound. I first noticed him in Greg Chappell’s test debut where he was hit for about 3 fours in a row by that player. I was expecting him to be taken off as did the crowd which cheered loudly when he took the next over from his end. Lever looked up, startled at first and then appreciative of his popularity, gave the crowd a long deep bow. Top player and a funny bloke.

Comment by the big bambino | 12:00am BST 29 April 2014

Yay. I think I pretty much saw almost all of his career and have read his auto biography.

Great article.

Had I have written it I would have spent a paragraph or two talking about his ODI exploits where his miserliness translated into match winning performances.

In his book he says “Unlike Paddles I don’t believe in goal setting – that said if I got three in a test I felt I had done my job”

I saw that Randall run out – not every bowler can do a mankad because they are in their delivery leap. Chatfield didn’t have much of a leap and that day he just stopped his action and took the bails off. Also saw the Botham run out and was bored to tears by the Boycott innings – the selfishness of the knock can only be appreciated if you were either watching it or had seen a similar knock. Just when you had given up all hope of him ever scoring a run he would hit a four.

It was Gavascar who proved you could score runs off Chatfield in ODIs when no one else could. Set a typical NZ target of 210 approx to win – Gavascar batted like Sehwag and took 10 runs off each Chatfield over and India romped for victory. The commentators could only mutter “If everyone can start batting like Sunny has in this game then scores of 200 will be very easy to chase down” – which proved to be prophetic words.

Horrible bowling action Chats had looking back on it. Well not horrible I have seen worse, but it was not the flashest.

Comment by Hurricane | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014

A story that captures Chatfield’s soul beautifully – especially the final paragraph;

Possibly your best effort to date Fred.

Comment by watson | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014

What great story telling again from Martin. As others have said in this thread to date, a real classic feature that I’m sure the man himself would enjoy reading.

Comment by James | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014

He was half the reason I started playing cricket, the first live test I went to was the one you talk about at the bottom where he score 20 odd not out at Carisbrook. Was thinking if only I could bat like Chatfield, well my dreams did come true.

Comment by GGG | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014

Video of the Lever incident and Chat’s innings against Pakistan.

[video=youtube;vAod0JeBnsk]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAod0JeBnsk[/video]

Comment by BeeGee | 12:00am BST 30 April 2014