Sex and Drugs and Rock n’ Roll

Gareth Bland |

Six years after Ian Dury and The Blockheads released “Sex and Drugs and Rock n’ Roll” on a B-side, Bob Willis’ England squad set off for New Zealand to embark on a three Test series that would forever be synonymous with the sentiments expressed by Harrow Weald’s finest alternative songsmith. With players like Botham, Lamb and Gower on board there would always be the potential for hijinks, of course, but England’s trip to the far Antipodes thirty years ago stands out as an early eighties high point for off-field shenanigans.

It would be difficult to imagine the current team engaged in Ashes combat creating such an enduring legend for their extracurricular activies. After all, the “goji berries, quinoa and flaxseed smoothies tour” does not have quite the same ring to it. Then again, even on top form, it is doubtful whether Captain Cook’s travelling band would have fared any better than their compatriots did thirty years earlier. Sir Richard Hadlee has claimed that his country’s 1973 vintage was the finest side he ever played in and, sure enough, they did possess heavyweight talent. The 1983 version, however, must surely rank as one of the greatest units the Kiwis have ever assembled and were nigh on unbeatable on home soil.

After a semi-final spot in the World Cup in June 1983 and a 3-1 series victory against New Zealand in the latter half of the English summer, Willis’ team headed off for New Zealand for three Test matches and three one day internationals, before moving on to Pakistan. Arriving in Wellington for the first Test, the Basin Reserve appeared to be conducive to seam and swing in dull overhead conditions. England laid claim to genuine batting depth with Derek Randall due to come in at number seven, behind Botham in the middle-order berth. The obdurate Tavare, condemned by selectorial decree to play the stonewaller against his own inclination, was accompanied by Chris “Kippy” Smith at the top of the order, with the number three, four and five spots being taken by a veritable eighties who’s who of Gower, Lamb and Gatting.

The home side elected to bat on winning the toss and soon fell to the experience of Botham and Willis. The all-rounder temporarily silenced his growing band of critics with an accurate display of seam and swing in helpful conditions. Still, the home side cannot have been happy as all batsmen from Howarth down to ‘keeper Ian Smith made starts but only Jeff Crowe, with 52, went on to assert himself. Botham finished with 5/59 and Willis, bowling with genuine speed, 3/37.

The tourists were making a meal of things when they slumped to 115/5 as Lance Cairns looked like recreating his Headingley heroics from the previous summer, prizing out Tavare, Smith, Gower, Lamb and Gatting in the process. It was then that Derek Randall joined Botham. Sun-hatted and initially watchful, Botham settled down to score one of the most accomplished of his fourteen Test centuries. With 22 fours and two sixes, he struck 138 with 232 coming in partnership with Randall. The Nottinghamshire man was content to play second fiddle at first and he faced over a hundred deliveries more to compile his 164. Last out with the score on 463, Randall had saved England and ensured a lead of 244.

At the end of day three with the New Zealand score on 93/2, it looked like Geoff Howarth’s men were odds on to go 1-0 down in the series. Still 151 short of making England bat a second time, there were still a further two full days to negotiate. It was here that two Test match careers came of age. One, a wily old professional of 30 years of age without a Test hundred to his name and the other, the Kiwi Boy Wonder, a 21 year-old believed by his compatriots to be destined for greatness . In contrasting style, with great skill, application and common sense, Jeremy Coney and Martin Crowe added 114 for the fifth wicket. When Crowe was dismissed for his maiden century, Coney continued. On and on he went until joined by the burly Lance Cairns at number 10. Adding 118, Cairns and Coney batted England out of the game. Cairns bludgeoned 64 and Coney was still there at the end, unbeaten on 174. Tavare and Chris Smith batted out time in pedestrian fashion to reach 69/0 but the game was safe.

For his first innings century and opening day five wicket haul, Botham was,once again, man of the match. The feeling was that England had squandered an opportunity. New Zealand, however, would have been elated to come away with honours even with the second Test at Lancaster Park, Christchurch, just over a week away.

The second encounter between the two teams in the 1983/84 series is one of the most infamous Test matches of England’s 1980s and possibly the most notorious that Christchurch has ever staged. In short, it proved to be a microcosm of all that was wrong with the English national side, and, by extension, the national game, during that decade. With the exception of Mike Gatting’s much heralded tour to Australia in 1986/87 England were victorious on only one other occasion during the eighties, and that was the surprise turnaround fashioned by David Gower’s team in India in 1984/85. The inability to knuckle down and play professionally under pressure in Christchurch thirty years ago has come to be seen as emblematic of England’s struggles throughout the decade.

Injuries meant that England were light on seamers and so, surprisingly, Sussex’s Tony Pigott was summoned for inclusion by tour manager AC Smith. Contracted to Wellington for the New Zealand domestic season, Pigott postponed his nuptials in order that he could make his Test debut. How often he must have wished he had not bothered. Not that he needed to postpone the big day, of course. England’s harrowing three days under Christchurch’s slate grey skies meant that the Sussex right-armer would have easily made it down the aisle in time, as his country’s capitulation meant that New Zealand were home and dry long before the original wedding date which was slotted for the scheduled fifth day of the Test.

Geoff Howarth won the toss and opted to make first use of what were widely expected to be favourable bowling conditions. With the exception of Willis, ever the stoic, England served up a smorgasbord of long-hops, half-volleys and four balls to allow the New Zealanders to salvage respectability and post a challenging first innings 307. At 87/4 this had looked in some jeopardy after Edgar, Wright, Howarth and Martin Crowe had all been dismissed. Then Richard Hadlee arrived to take charge of New Zealand’s innings at 137/5. By the time he was dismissed, caught behind off the bowling of Willis by Bob Taylor, he had smashed 99 out of 144 runs scored while he was at the crease. He was especially severe on Pigott, who could perhaps have been excused his debut match nerves, and Botham, who had no such excuse to offer.

Botham went for 88 from his seventeen overs while Pigott finished with figures of 17-7-75-2. As if squandering agreeable bowling conditions was not bad enough in itself, worse was to come for England. Much worse, in fact. For the final over of the first day, Geoff Howarth tossed the ball to slow left armer Stephen Boock, returning to Test cricket after a hiatus of three years. With his final delivery of the over he nudged past the tentative forward prod of Graeme Fowler to hit the off stump. From an overnight position of 7-1 England never recovered. Forty nine overs later on the second day England had been dismissed for 82. Only Lamb, Botham and Gatting had reached double figures, while three wickets each went to Hadlee, Cairns and Chatfield. Incredibly, Hadlee had bowled his 17 overs at a cost of just 16 runs. Falling well short of the required follow-on target, Geoff Howarth asked England to do it all over again. Alas, things did not get any better.

At 33-6 in their second innings England were only spared the ignominy of failing to complete their half-century thanks to a jaunty partnership from Randall and Bob Taylor. When Randall was eighth out at 76 he had contributed England’s highest score of the match with 25. Eventually Norman Cowans was caught behind off Hadlee by ‘keeper Ian Smith and England had been dismissed for 93 in 51 overs. Hadlee, unquestionably man of the match, finished with 5-28 off 18 overs to match his three first innings wickets and his cavalier first innings knock of 99. In twelve hours playing time, by the third afternoon, it was all over.

What had gone wrong for England? How could they have so manifestly failed to adjust to conditions and play a “normal” game when New Zealand had demonstrated such cool, clinical professionalism? The furore created by the pitch conditions during the build up, and on the first morning, gives us some idea. Geoff Howarth, New Zealand’s skipper, argued that real doubts about the quality of the surface had entered into the heads of Willis’ men:

“We were confident about playing anyone at home. But with this particular Test – and 20-20 hindsight is nice – it was perhaps lost before a ball was bowled. There was a provincial game that ended quickly and the pitch got a real slating. I think this got into the minds of the English players”

Tony Pigott felt that it “was cracked before we started. It wasn’t a good pitch”. Even so the Sussex debutant was alarmed at Botham’s battle plan, especially as the wicket appeared to be receptive to seam. Pigott lamented:

“Before we went out, we had a team talk about how to bowl to the New Zealand batsmen. Botham’s advice was: “Bounce Coney, bounce Crowe, bounce Hadlee, bounce Wright. In fact, bounce them all.” So, on a pitch where all we had to do was bowl decent line and length, we tried to bounce them out”

When it came to their turn to bat England seemed fixated with the supposed gremlins in the pitch and never came to terms with a probing Kiwi seam attack, who achieved what the England bowlers had manifestly failed to do: bowled straight and kept to a good length. The returning Stephen Boock, watching his team-mates in awe, added:

“I think I fielded at short leg for a lot of that match – with a helmet but not much other padding. I was trying not to get hit, so I spent most of my time watching the batsman, but you could tell when Richard was bowling well, because of a late flick of his wrist. The whole New Zealand attack was made for that pitch, but he was lethal”

Even so, in the view of Geoff Howarth, it seems that events on the first morning when Bob Willis had the new ball convinced England’s batsmen that this was a very dodgy surface indeed:

“In the first over of the Test, a ball from Bob Willis flew over John Wright’s head. That sowed the seeds of doubt, because of what they’d read about the pitch. They just played in a very cavalier style after that. New Zealand wickets always tend to do a bit, but this wasn’t an awful pitch”

Perhaps the most telling remark, however, and one which casts light on how England were perceived by their opponents during the period, came from Stephen Boock. Twenty-nine years after the event, Boock observed:

“We could tell there was a strange culture around the England team at that time. It was also a good era for us. Almost every series we played, we started as underdogs but we were also determined to stand up for ourselves”

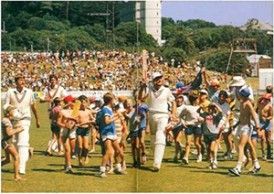

Strange culture or not, England regrouped quickly to draw the final Test of the series in Auckland. Neil Foster and Vic Marks were included, Tavare was jettisoned in favour of Chris Smith and out went Gatting. Willis again lost the toss and Howarth opted to bat first. Centuries from Wright, Jeff Crowe and Ian Smith meant that the home side posted 496. On a surface which Wisden described as “turgid” England achieved a painstaking and laborious 439 in reply. Randall’s second century of the series, “Kippy” Smith’s 91 and Botham’s briskly welcome 70, with 10 fours and two sixes, kept England afloat. Botham aside, it had been heavy going, as the tourist used up 227.3 overs in compiling their first innings total. All that was left was five overs of the Kiwi’s second innings to ensure a draw and a series victory for the host nation by 1-0, the first over England in their history.

England completed a 2-1 win in the limited overs series to put some gloss on their tour of New Zealand before they headed for Pakistan. When England arrived there they were, in the words of Tony Lewis, confronted by “foot-in-the-door newshounds from the Mail on Sunday”. Essentially, some of the players were believed to have been bad lads in New Zealand, and accusations of sexual promiscuity and drug taking were at the root of the “Mail on Sunday’ allegations. As Lewis explained:

“A girl named Mary Burgess had written her name in cricket history. She had given the Mail on Sunday a sworn statement that she had witnessed Ian Botham in a drug-taking sequence in a private room. “I looked into his eyes and thought “Wow!”. He looked straight through me. He was spaced out – his eyes were down in his cheeks”

The allegations were, of course, strenuously denied and Botham returned home from the sub-continent in need of a knee operation after the first Test. Many, however, saw his return to England as an admission of guilt. Those close to the all-rounder knew that he had needed the surgery for some time, however, and any delay would have prevented his return to full fitness for the 1984 summer series with West Indies. The damaging allegations rumbled on, though, sowing the seeds of mistrust between press and England players.

The sore would fester until reaching its peak in the Caribbean in 1986, after which, exhausted, Botham confessed to recreational use of cannabis in the very same “Mail on Sunday” in the spring of that year. It was, however, seen in the cold light of day for what it was: a ruse to take a break from the spotlight that had so distracted the Somerset all-rounder and his team-mates for some time. Botham’s “break” from international cricket came sure enough, though, as the TCCB banned him for the duration of the 1986 home summer, before he was able to return, in his own inimitable fashion, for the season’s swan song at The Oval in late August.

These unnecessary and unhelpful diversions began on the 1983/84 tour of New Zealand, and the alleged improprieties gave the tour its infamous sobriquet – “sex and drugs and rock n’ roll”. Although the more lurid newspaper allegations turned out to be largely guff, the “strange culture” around the team that Stephen Boock observed cannot be so lightly dismissed. In his 1991 Wisden essay heralding Graham Gooch’s belated ascent to cricketing greatness, Simon Barnes more or less nailed it when he identified what he saw as a team debilitated by an inner clannishness centred around Botham:

“There is a case for saying that Headingley 1981 is one of the greatest disasters to have hit England’s cricket. Certainly, it lunged into a pattern of self-destructiveness as the echoes of that extraordinary year died away. The England team became based around an Inner Ring, with Botham at its heart: Botham, self-justified by his prodigious feats during that unforgettable summer. To be accepted, you had to hate the press, hate practice, enjoy a few beers and what have you, and generally be one hell of a good ol’ boy. Like all cliques, the England clique was defined by exclusion. Nothing could be more destructive to team spirit than a team within a team, but that was the situation in the England camp for years”

Indeed, as that heady summer receded into the past England’s performances – especially overseas – became increasingly indifferent. At the moment of Botham’s greatest hour in the summer that brought England’s fans so many indelible memories, the senior supporting cast that had comprised the side in 1981 shuffled off to South Africa. Some may have been past their best but Boycott, Knott, Old, Hendrick, Lever and Underwood had no obvious understudies in the domestic game. Moreover, Gooch, Emburey and Les Taylor were in the prime of their careers. In their stead came players who proved that there had been a demonstrable break with the technical standards established in the near past. There were batsmen who seemed incapable of batting for lengthy periods while compiling match winning scores when the chips were down and, as proved on the 1983/84 tour, bowlers who appeared not to be able to master the fundamentals of bowling at Test match level.

As if to prove the case Willis topped the bowling averages by some margin, with 12 wickets at 25, while Botham claimed seven scalps at a cost of 50 a piece, Cowans five at 30 and Neil Foster’s four wickets came at a costly return of 57 runs each. Willis, let us not forget, was by then approaching his 35th birthday and had begun his own international career when Cowdrey, Illingworth, Boycott, John Edrich and Snow were all in their pomp.

In the crucial opening batting positions, the cupboard seemed pitifully bare, as, indeed, it had done on the previous winter tour of Australia. The absence of Gooch and Boycott was by now painfully apparent. Just over a decade earlier in the summer of 1972 the England selectors could afford to jettison Boycott in favour of Brian Luckhurst after two lean Tests. In the New Zealand summer of 1984, however, Graeme Fowler, Chris Smith and Tavare all appeared to be either ungainly, ineffective or technically maladroit in seam friendly conditions.

That sage of New Zealand cricket writing, Don Cameron, for one, seemed shocked at the decline in the quality of players from the game’s mother country. After witnessing the Christchurch debacle, he was moved to note:

“Threading through the mind came visions of past Englishmen, especially of men of Kenny Barrington’s steel or Ted Dexter’s audacity. One could not imagine Barrington capitulating so completely. He would have got the tip of that craggy nose even closer to that defiant chin and he would have fought for survival. Dexter would have batted with bitter reprisal, or Colin Cowdrey with quick-witted technique. It might be unfair to compare the men of the present with the heroes of the past, but these are the men who linger in New Zealanders’ minds”

In the middle of all this was a player, Botham, who was beginning to find the burdens placed upon him more onerous than those heaped on any English player in memory. With a new media age focusing as much on his off-field activities as for those on it, it is perhaps not a surprise he occasionally wilted.

This is not to say that England’s 1983/84 tour of New Zealand was a case of victory for the diligent journeymen over flaky and disinterested tourists. This would be to make a grave mistake, as Howarth’s men formed one of the most gifted sides his country has ever produced. Near invincible at home, they had broken Lloyd’s West Indians in 1979/80, more than matched Greg Chappell’s Aussies in 1981/82 and outplayed England comprehensively at Christchurch during this summer. Indeed, throughout the decade they remained unbeaten at home, winning seven and drawing four series. Furthermore, they went on to best England on their own patch in the 1986 summer.

Augmenting the great and peerless Hadlee, an opening batting pair of Wright and Edgar were skilled and durable, while the stylish Geoff Howarth perhaps did not make the runs his talent suggested, although his leadership was crucial. Coney came of age in 1983/84 and was a more than capable back-up medium pacer. Martin Crowe began to develop the reputation that would see him anointed as one of the game’s greats, while Ewen Chatfield and Lance Cairns could be formidable back up to Hadlee in seaming conditions. In Warren Lees and Ian Smith, the Kiwis were lucky to have a pair of wicket keepers competing for the Test role who would have been the envy of many a side. Geoff Howarth acknowledged the strength of that era in his country’s history when he said:

“Most New Zealand sides have been made up of one or two top-class international players and then a host of good provincial, first-class cricketers. But this team in the ’80s was one of those where I believe we had maybe seven top players, and that made all the difference”

For England, though, they would continue to wrestle with the troubled inheritance of the 1981 series as they picked themselves up and headed for Pakistan and the concluding episode in their 1983/84 overseas sojourn.

Article needs more sex drugs and rock and roll. Good article.

Comment by Hurricane | 12:00am GMT 7 January 2014

I think I’ve seen it claimed (maybe in “Lamb’s Tales”?) that Cowans was England’s best bowler in the 2nd Test.

Comment by AndrewB | 12:00am GMT 7 January 2014