Lost in the Long Grass – Trout v Maco

Martin Chandler |

Fairfield Books have kindly agreed to us publishing the following extract from John Barclay’s latest book, “Lost in the Long Grass”. It is a wonderful story from a superb book which Martin has reviewed here,. You can buy the book, very reasonably priced at GBP15, directly from the publisher or from good book shops everywhere.

This is quite a story, an unusual one of which I am not in the least bit proud.

I tapped at the crease with my bat while Marshall reached the end of his run-up. Normally I didn’t mind facing fast bowlers, even the fiercer ones. If nothing else, death came quickly and often without fuss. Nothing like the tortuous agony of being tormented by spin. Yes, it demanded courage and a little technique but not so much brain and was less humiliating.

“Who’s the fastest bowler you’ve ever faced?” I am always being asked that. Roberts perhaps, Holding, Daniel, Hadlee or Procter on his day. Walsh was pretty quick too, and Croft, and Sylvester Clarke whom I nearly forgot. He could be lethal. Imran Khan as well, but I only ever faced him in the nets and I don’t think that really counts. All of them were fast on their day but none more likely to get you out than Marshall. He was the best, I should say, and probably the most dangerous too.

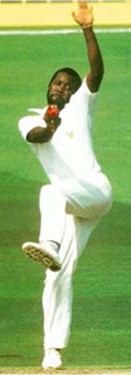

Marshall approached the crease from a wide arc with short rhythmical strides. He was not tall for a fast bowler, probably less than six foot, and built more for stamina than pace. He was a thoroughbred – stocky, strong and athletic – more of a Derby runner than an out-and-out sprinter. He was certainly a stayer and a willing one at that.

It was August, cricket week at Eastbourne, the first day of the match against Hampshire, and we were in trouble. For various reasons we were missing Parker, Greig, Gould and Le Roux. Imran was back from the World Cup but with sore shins and so only able to bat, not bowl, while I was handicapped by a damaged finger which impeded my freedom with bat and ball. In short, Sussex were in a sorry state and not best equipped to face the most incisive and penetrating bowler in the world.

Marshall had savaged our early batting. Mendis, Cowan, Green, Heath, Colin and Alan Wells had all fallen cheaply. The score was 83 for six when I joined Imran who remained our main hope of salvaging respectability and avoiding humiliation.

You will notice the name Cowan in our line-up. Not a household name in the world of cricket, he was playing on the back of a stunning performance in a World Cup warm-up match against Australia earlier in the summer. In it he bowled 8.5 overs and took five for 17, a performance which earned him the nickname of “Wrecker Ralph”, that being his Christian name. It is not plain how this achievement bounced him up to number three in the batting order, but in the event he was out first ball and I don’t recall his bowling. For what it’s worth and irrelevant too in this context, Ralph played football with some success for Lewes Town and now teaches geography at Caterham School in Surrey. He was briefly one of my favourite cricketers but, to be fair, one who rarely assisted the Sussex cause. In that he was not alone.

By early afternoon Imran and I had staged something of a recovery, taking the score to 145 for six. I had only scored 13, but Imran had just reached his hundred. It was a warm day at Eastbourne, a holiday crowd and atmosphere to match. Picnic lunches, a beer or two, a bottle of wine, strawberries and raspberries were the order of the day – short sleeves, shorts and sunbathing too for the more exotic.

I loved Eastbourne and loved playing there. In the old days it was one of the best batting pitches in the country, evenly grassed and low of bounce. The ball came on nicely into the middle of the bat. I had even made some runs at Eastbourne from time to time, never a hundred but 60s, 70s and 80s, though the plurals attached to those figures may be a little fanciful. In 1977, I think it was, I got struck on the ear by a ball from Collis King when going well and had to spend an afternoon in Eastbourne’s hospital, but mainly I have happy memories of this famous seaside town.

There was tennis just across the road at Devonshire Park where I watched my daughter play in the finals of the under-12 Sussex Tennis Tournament on Centre Court. She hit an easy forehand into the net when on match point and two games later lost the match. Ice creams all round to counter the bitter taste of disappointment. The courts are but a stone’s throw from the sea, pebbly beach, promenade and pier, where the band plays and soothes away the anxieties of everyday life.

With the sea air carrying with it the smell of seaweed and salt, I was now aware that Marshall, with his curved run-up, not dissimilar to that of John Price of Middlesex in his heyday, was preparing to bowl. He ran in on tip toes. “Keep still,” I said to myself, “stand upright – back and across.” Les Lenham years earlier had taught me how to face fast bowlers. Strangely enough I wasn’t scared. In many ways I preferred facing Marshall to the medium pace of Tremlett who was bowling at the other end. I left him to Imran. He didn’t mind.

So back and across I went. Marshall’s arm came over high and fast. Simultaneously I heard a thud as the ball hit the pitch just short of a length. I sensed it was rearing up towards my chest. Uncertainly I fended at it. The ball passed by my side without causing harm but, as it did so, just brushed my glove on its way through to Hampshire’s wicket-keeper, Bobby Parks.

After a short pause the Hampshire fielders (Parks, Pocock, Nicholas, Greenidge, Jesty) and the bowler bellowed out their loud appeal, the outcome of which was, to their eyes, bound to be successful.

I had in the process of playing my shot, at best a feeble prod to leg, turned in the direction of Parks’ diving glove and Eastbourne’s large town hall clock, whose bongs boomed out every fifteen minutes. I saw the catch cleanly taken and yet remained glued to the crease amidst much noise from the opposition. I knew the ball had grazed the side of my glove, and the Hampshire close fielders and bowler knew it too. And yet I stood there in defiance of the evidence.

The umpire at the bowler’s end was David Shepherd. He had been a most popular cricketer, a middle-order batsman with Gloucestershire in his playing days. Somewhat stout in stature he became a first-class umpire in 1981 and immediately fitted the bill and warmed to the task. We all liked and respected him. Indeed, in the late 1970s I had sat with him behind the bowler’s arm in the pavilion at Bristol and encouraged him to pursue an umpiring career. Subsequently he took the exams, started with some second team and university matches and never looked back. I stood at the crease stubbornly in front of a man I trusted and who, up till now, trusted me. It was a bad moment.

After a pause and having given time for consideration, Shepherd said, “Not out”. Marshall expected players to “walk” when he was bowling and, for the most part, they did so obligingly, preferring the comfort of the pavilion to the battleground at the crease. Amidst the confusion Shepherd called “Over” which helped remove the tension for a moment.

I wandered down the pitch to greet my partner Imran who grinned at me. “A brave thing to do, Johnny,” he said, followed by, “I think I had better get down that end next over.” It was a generous gesture and one which I was happy to go along with. I felt this was a moment when an overseas player could truly show his worth.

I returned to the non-striker’s end and, as I did so, Nick Pocock, the Hampshire captain, strolled past me. “Did you hit that one?” he asked. “I’m afraid to say I did,” I replied sheepishly and with shame in my voice. “I thought so,” he said and left it at that. Except that he didn’t. During the next over, bowled by Tremlett, he relayed a message to Marshall at deep fine leg outlining the gist of his brief conversation with me. By the time Tremlett’s over came to an end Marshall’s mood had darkened.

The good thing about the next over to be bowled by Marshall was that I wasn’t facing it. Imran and I had contrived to swap ends. After all, he had just reached his hundred and was our senior overseas player and, I expect, he got paid more than I did too. But he was happy to take the flak and did so uncomplainingly, even with the suggestion of a smile on his face.

At the non-striker’s end I was fidgeting about, feeling embarrassed. I hated incidents at the best of times and particularly when they involved me. With my head bowed I attempted to tender my apologies to Shepherd. “All part of the job, my lad,” was all he said. I felt uncomfortable and slightly sick. What made matters even worse was that the crowd, ever loyal to the home captain, had rather taken my side and saw Marshall as the evil-doer of this confrontation.

Amidst my anxiety the game continued with Marshall running in as fast as ever to bowl at Imran. When he reached the crease something unforeseen occurred. As he prepared to bowl, he stopped suddenly; no mean feat given his acceleration, and whipped off the bails at the bowler’s end. He appealed loudly as I had drifted absent-mindedly and unenthusiastically out of my ground, not in the least bit wishing to get down the other end. “Howzat,” he bellowed, glaring at me and Shepherd and the crease more or less simultaneously. Shepherd was startled and looked a little non-plussed. I think he asked Marshall whether he wished the appeal to stand. “You’ll have to give me out,” I said, turning to Shepherd. “Indeed I think I will,” he replied and raised his finger as the umpire’s symbol of execution.

I made my way slowly back to the pavilion and was aware of a few boos emanating from the normally serene Saffrons crowd. I was about half-way there when Pocock, the Hampshire captain, came running over from his position at slip shouting, “No, no, no, we don’t play cricket like that in Hampshire. If it’s all right, Shep, I’d like to withdraw the appeal.”

At this stage I was more than happy to be out; in fact it was a merciful release from the hostile ordeal. “Don’t worry about me,” I shouted to Pocock, “I’m happy to go quietly.” The upshot of these shenanigans was that I was given a reprieve and had to return to the non-striker’s end to continue the battle. Marshall finished the over without further incident, so far as I can remember, but at the end of it he hurled the ball fiercely at Pocock and declared he would do no more bowling.

Imran, never one to miss out on a bit of fun, came down to talk to me at the end of the over and said, “Johnny, that’s a fine way to see off the country’s leading fast bowler.” For a moment, despite my shame, I felt I had done something to ease the pain.

So Marshall, who was comfortably the most successful bowler playing county cricket at the time, had banished himself to the boundary in something of a sulk. Someone had to bowl instead and the lot fell to Trevor Jesty. Jesty bowled relatively tempting away swingers at gentle pace and, by comparison with Marshall, was a joy to see holding the ball. Imran certainly thought so. It took just three balls for him to lose his head completely and fall to a jubilant Jesty, bowled middle stump.

Returning to Marshall in the end that day he did get me, caught brilliantly one-handed in the gulley by Gordon Greenidge. He deserved that wicket, for I had treated him badly and lost a bit of honour too.

Imran was undoubtedly a magnificent all-rounder as well and an intriguing person to have in the Sussex side but, if I could have had first pick of all the overseas players in county cricket at that time, I think I would have chosen Malcolm Marshall. He was a truly great cricketer and a very friendly chap too – off the field.

A good read. Contained a surprisingly large echo of my own summer 2013, in fact – a game down at the Saffrons, a fantastic summer’s day, and Les Lenham on the boundary watching on.

We even had a controversial non-striker’s end run out (Les’ own grandson in fact) which ended with the batsman being recalled on a matter of principle, too (that was the following day, though)…

Comment by Neil Pickup | 12:00am BST 5 October 2013

awesome anecdote. Imran WAG.

Comment by hendrix | 12:00am BST 5 October 2013

Maco rules! I think after every spell by a dangerous bowler, one over should be given to a tosser so that the batsman may, as the story says, “completely lose his head with joy”, and get out!

Comment by Harsh Agarwal | 12:00am BST 6 October 2013