Playing for Keeps

Neil Pickup |

In the aftermath of the 2005 Ashes series, I wrote this article, bemoaning the state of wicketkeeping in the world game, and amongst the English shires. Now, seven years later, it doesn’t seem like a day at a ground goes by without the topic of conversation turning to glovework.

Since my original piece, England have at least managed to find a wicketkeeper worthy of the name, and one who also happens to be worth his place in the side on batting alone. Whether things would be so settled had Matt Prior not shown such commitment to improving his skills behind the stumps since 2007’s horror tour to Sri Lanka, however, is another question entirely: one which the revolving door of ODI selection suggests might not have a final answer. Around the world, New Zealand have picked Test sides containing three wicketkeepers, only for pundits to argue that the man in possession is weakest stumper of the trio. The West Indies have swapped between Carlton Baugh and Denesh Ramdin, and then there’s Pakistan’s answer to the Chuckle Brothers, the Akmal family. In my own world, I’ve made the switch from emergency stand-in to out-and-out keeper, and am continually concerned by the fact that I keep on being praised for my performances.

Nevertheless, taking the gloves on a regular basis has further opened my eyes to the depths of the wicketkeeper’s art. With the worst summer since records began in 1766 ravaging England’s already slow wickets, the onus on batsmen to use their feet and take the pitches out of the equation has increased. For any keeper worth his salt, the sight of fancy footwork should mean just one thing: call for the helmet (more on those later), and get your gloves in the dirt. A batsman plays totally differently when you’re just inches away, as freedom becomes fear and punches become prods – something I’ve seen from the closest quarters this summer: most recently as an opposition stumbled from 40/0 to 60/3 in short succession (bowled, caught mid on, and caught behind – all to leaden-footed wafts) after I stood up to the change bowling.

I also recall an interesting conversation at the side of a County youth fixture earlier in the summer: as my team chased down its target, our (8-year-old) keeper wandered over to the scorebox, and – with all the innocence of youth – asked, “Do you think this keeper’s any good? I don’t.” I commented in my first piece on the paucity of wicketkeeping at district junior level, but this is a malaise that has spread further up the food chain to the extent that a child so young can see the signals loud and clear. I have barely seen a keeper up to the stumps against a medium-pacer, but the problems run deeper: staying down with the bounce, holding the basic squat or “Z” position, keeping hands ahead of the body to allow space for a smooth take, and even fundamental basics such as gauging distance off fast-medium bowlers, or keeping hands together to maximise the catching area. As far as I’m concerned, these are non-negotiables – utter fundamentals of the keeper’s skillset – yet they’re, as our 8-year-old noticed, absent all too often.

Nor is it a skillset that is difficult to obtain with the correct practice. I am accustomed, now, to beginning a new season by playing the game of “create a keeper”: identifying the essentials (balance, catching skills, absence of fear) and then targeting the basic technique – starting with standing up to the stumps, and taking the ball as close to the crease as possible. I have seen more than one boy make his wicketkeeping debut in May, only to be playing representative “B” team cricket – in a side capable of going toe-to-toe with the best any other county can offer – by August. Today, however, saw the first round of this summer’s county trials: and one wicketkeeper. So why the dearth?

Most charitably, it must be considered that the vast majority of junior clubs are dealing with huge numbers of players against limited coaching resources, and coaches who haven’t kept wicket themselves then lack the confidence, or the time, to devote to glovework. So what is the way forward? Well, as far as I’m concerned, everybody should have a chance to cover the basic skills of keeping wicket – developing both an understanding of the task and key transferable skills that will only help fielding, and go a very long way towards tackling the “ball shyness” that is often a direct result of poor posture and poor balance.

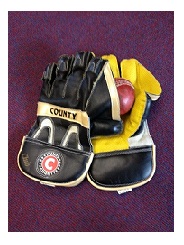

The role of the helmet (or facemask – it’s not worth differentiating between them) in the wicketkeeper’s kitbag is another interesting point of discussion. I cannot understand, whether against spin or pace, why anyone would stand up to the wicket without protection. Yes, you don’t need your grille for the routine takes outside off: but it’s not the routine take that causes the problems. It’s the freak deflection, the top edge, the gloved pull down the legside, or the flying bail. Yet, standing back, it sometimes seems as if wearing a helmet is a substitute for proper preparation. Why wear a helmet there, and not at slip? Why not ask a bowler to wear one – certainly, some of the worst injuries I’ve heard discussed at junior level have come when the ball has been hit – hard – straight back at the bowler. To me, wearing a helmet standing back immediately betrays a lack of confidence and self-belief.

The idea of “compulsory” wicketkeeping training will also work to raise the profile of the wicketkeeper as a specialist, and the appreciation when the difficult is made to look routine. Call me biased, but it feels like the attention of the wider world falls only on the gloveman when he makes a mistake. Like a football referee, he is treated as a man best out of the limelight – yet no other position on the field of play is so critical to a fielding effort: when has a great team carried a poor wicketkeeper? Why does a fielder get rousing applause for a slide on the boundary and a throw into the keeper’s ankles, only for the crowd to ignore the stumper’s efforts to collect the ball in the dirt?

Perhaps I’ll return to this theme in another seven years, in a T20-driven world where the impact of a moment’s brilliance behind the stumps counts for nought against the arc of a DLF Maximum – or perhaps the ability of the true keeper to swing the balance, and break a partnership, in an increasingly batsman-dominated game might be fully valued.

I know which future I’d rather live in.

Leave a comment