I Know You, You’re The Destroyer

Martin Chandler |

Devon Malcolm was born in Jamaica in 1963 and lived there until he was 17. In 1980 he finally left the country of his birth to join his father in Sheffield, where he had worked for many years in order to support his family back in the Caribbean. Malcolm had bowled fast back home but, for his first two years in England barely played the game at all and it was only a chance encounter with a fellow Jamaican that caused him to start playing in the local leagues. Having started late Malcolm quickly moved up through the various levels of the game in South Yorkshire, and by April 1984 he found himself opening the bowling for a Yorkshire League XI against the Yorkshire first XI in a one day match.

The Yorkshire innings was begun by the legendary Geoffrey Boycott together with the next Yorkshire opener to play for England, Martyn Moxon. Malcolm yorked them both, Boycott for eight and Moxon for a duck. Boycott wrote later throughout my First Class career I have rarely been out to a yorker …… therefore it had to be good to get through – and it was! Yorkshire showed an immediate interest, but these were the days when a Yorkshire birthplace was a pre-requisite, so it was Derbyshire who signed the by now 21 year old Malcolm later that season.

For four years Malcolm was classified as an overseas player so, with New Zealand opening batsman and the great West Indian paceman Michael Holding also vying for the single place available, his First Class appearances were limited until 1988 when he was able finally to play as an England qualified player. He played in all but three of Derbyshire’s County Championship fixtures and took more than 50 wickets, albeit he paid almost 30 runs each for them. Wisden described him as On occasions…..startlingly fast; on others his tendency to pitch consistently short led to severe punishment and there seemed to be no middle ground. As Boycott was to comment later on the lethal yorker from wide of the crease was attempted all too rarely.

The following season saw Malcolm play in just nine Championship fixtures, Derbyshire being so well off in the pace bowling department that they were able to rotate their bowlers. There were inevitable fewer wickets, but they were more than six runs cheaper. This time Wisden said sheer speed helped him to achieve a good strike rate in county games. He has made great strides since being engaged as a novice in 1984.

The summer of 1989 was not a happy one for English cricket as the Ashes were wrested back by Australia in as one sided a contest as there has ever been, with Australia recording thumping victories in four Tests, and being well on top in the two that rain helped England to save. In the clamour for change as humiliation followed humiliation it was hardly surprising that the fastest bowler in the country was called up for the fifth Test. The plus point was that Malcolm’s first Test wicket was that of Steve Waugh, dismissed for a duck in a series in which he ended up averaging more than 126. In cricket however context is everything and Australia finished the first day on 301 without loss, and at the end of the only innings Australia required Malcolm had 166 in the runs conceded column, with just Waugh’s wicket to show for his labours. One suspects he may well have been grateful to the intercostal strain that kept him out of the final Test. But at least the Chairman of Selectors noticed his performance in the fifth Test, Who could forget Malcolm Devon? were the words Ted Dexter has never been allowed to forget.

Despite Trent Bridge Malcolm’s pace was still enought to get him a place in the side for the West Indies in 1989/90. The comment of Chairman of Selectors Ted Dexter, that England were now capable of fighting fire with fire attracted some ridicule, but proved not to be so far wide of the mark as it sounded. England won the first Test, their first victory over West Indies for almost 16 years and it was Malcolm the fielder who was the catalyst. Viv Richards won the toss on the first morning and chose to bat. Gordon Greenidge and Desi Haynes set off in imperious fashion and looked untroubled by the England attack. Malcolm’s poor eyesight meant that his ground fielding, catching and batting were all rather less than reliable but, as Greenidge found out to his cost, when he needed it he had a wonderful arm. A peerless flat throw following a misfield down at fine leg was in Russell’s gloves in no time and Greenidge was comfortably run out. There was only one wicket for Malcolm the bowler in the first innings, but it was that of the West Indies captain. Richards again, as well as three others in the second innings, meant that Malcolm had made a very real contribution to the famous victory.

After the rain took away any chance of play in the second Test Malcolm, with what was to be the first of his two ten wicket Test hauls, played the lead role in what would, without some fairly cynical time-wasting by the hosts, have become an unbeatable 2-0 lead. As it was England and Malcolm rather lost their way in the final two Tests but, now established, Devon was, for the only time in his career, selected for the entire English summer of 1990. In the first half, against New Zealand, he was excellent. His return against India was disappointing, but that was not a series for bowlers generally, so he was a certainty for the following winter’s Ashes squad.

Australia beat England 3-0, but once again Malcolm played the whole series, and while his 16 wickets were costly, at more than 41 runs each, no other England bowler took more than 11. Malcolm felt drained when he got back to England as, in addition to taking the most wickets, he had also bowled the most overs of the England bowlers and, after he was dropped following two lacklustre performances against the 1991 West Indian tourists he became a bit part player, the out and out speed merchant who was wheeled in for special occasions and who, prior to the South African series in 1994, usually disappointed.

Malcolm’s selection for the First Test against New Zealand in 1994 was, in light of his recent history with England and largely ineffective early season form, something of a surprise but, after just two wickets at Trent Bridge, his subsequent omission from the starting line-up at Lord’s for the second Test was not. Malcolm was furious at his treatment nonetheless. It wasn’t that he thought he had bowled well at Trent Bridge, he knew he hadn’t, but what he did not like was the manner of his being stood down 24 hours before the Lord’s Test began. England had a new Chairman of selectors, Ray Illingworth, and his and Malcolm’s less than harmonious relationship had gone wrong from the start.

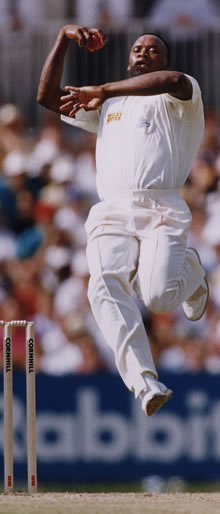

His disappointment notwithstanding Malcolm went back to Derbyshire and enjoyed one of his most productive summers for them leading, inevitably, for demands from press and public for his return to England duty at his favoured Oval for the final Test of the summer’s second series, against South Africa, which England needed to win. The call duly came, and what followed was the defining episode of Malcolm’s career.

The Oval wicket was rock hard, and after Kepler Wessels won the toss and elected to bat Malcolm made the ball fly and South Africa had lost four by lunch, Peter Kirsten losing his leg stump to the sort of yorker that would have made Boycott purr. That was to be Malcolm’s only success in an innings which, thanks largely to a sixth wicket partnership of 124 between Brian MacMillan and David Richardson, eventually totalled 332. There was however one more significant moment for Malcolm when Jonty Rhodes was forced to retire hurt after being struck on the head. Rhodes is an epileptic, and there were very real concerns for his welfare as he was taken to hospital for a scan that proved, thankfully, to be precautionary only. The delivery in question had not got up as Rhodes clearly expected, so much so that an LBW shout might have been appropriate, so there was no question of Malcolm being to blame.

England’s reply began badly but some decent batting by the middle order meant that it was 293-9 when Malcolm came to the crease. His batting tends to be viewed as something of a joke, and his technique was indeed sadly lacking. That said Malcolm the batsman did not want for courage and was, on occasion, capable of hitting the ball a long way, probably most famously in the New Year Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1995 when he scored a rapid 29, his highest ever Test score, including two sixes from the bowling of Shane Warne. But the fast straight delivery was the best way to get rid of him, so the decision of Fanie de Villiers to bowl him a bouncer first up has always seemed an odd one. No doubt the blow Rhodes sustained had something to do with it (Malcolm claims that the close fielders encouraged De Villiers to bounce him both before and after the fateful delivery) and in addition De Villiers himself was probably still angered by an earlier failure to get a decision against Graeme Hick, his silent protest at which was to cost him 50% of his match fee.

Malcolm was expecting a yorker, and says he never saw the ball that flew into his helmet grille, right between his eyes. The helmet was damaged and required replacement. Malcolm was dazed, but unhurt. He heard Brian MacMillan and Darryl Cullinan shout Give him some more of that and was furious. Exactly what he then said is lost, but all who heard it are agreed it was something like You guys are going to pay for this, you guys are history. De Villiers described Malcolm as …someone with a bigger mouth than most, and dismissed the comments as an act of bravado.

Less than twenty minutes later on that sunny Saturday Malcolm was pawing at the ground waiting to unleash himself on the South African batsmen. They didn’t know what hit them as half-brothers Peter and Gary Kirsten, as well as Hanse Cronje, were all back in the pavilion with just a single on the board. First to go was the younger Kirsten, completely tucked up by a delivery that was simply too quick for him as he popped up a return catch. His older brother then essayed a hook at a delivery that was far too straight for the shot and his top edge flew to fine leg. As for Cronje he played a textbook forward defensive shot. The problem was the delivery was through him and had shattered his stumps before he had completed the shot.

After that skipper Wessels and Daryl Cullinan started to repair the damage and saw the visitors through to lunch at 40-3, and beyond that with a determined stand of 72. At that point however Wessels, who was batting with a broken thumb, decided not to move his feet and in playing an expansive drive at a full length delivery wide of off stump he presented England wicketkeeper Steve Rhodes with a regulation catch. If Malcolm needed a shot of adrenalain it must have been provided by the sight of his two tormentors from his innings, MacMillan and Cullinan, now coming together. It was at this point however that England lost their way again. Gooch dropped MacMillan, and 64 were added, but just before tea, having switched ends, Malcolm returned to remove MacMillan, who was caught at slip with the total on 137. Straight after tea Malcolm removed two more, first Richardson was pinned LBW, and then there was a spectacular dismissal for Craig Matthews two deliveries later. A delivery that pitched on a good length outside off stump seared through the batsman and was taken high down the leg side by Rhodes. Gary Kirsten wrote later that the ball grazed the thigh pad and flew down the leg side. There was a half-hearted appeal but it was good enough for Craig and he started walking without so much as a sideways glance in the direction of the umpire.

At 143-7 Rhodes now came to the crease. England were, naturally, fired up but Rhodes batted solidly and Cullinan continued to look for runs. The pair added another 32 before Darren Gough finally coaxed a mistake out of Cullinan when he was on 94. Rarely has a century been more richly deserved. That was 175-8 and the last two wickets added no more to the total as Rhodes attempt at a flashing cut gave his namesake another catch, and a pensive looking Alan Donald went two deliveries later, comprehensively bowled. England went on to square the series, losing just two wickets in getting the 205 that they needed for victory.

We were swept away by the most destructive piece of fast bowling I have ever seen. was Donald’s verdict, echoed by Kirsten the younger, who later said I’d never seen fast bowling like it before. He was particularly quick, and the result was chaos. It might have been expected that the Chairman of Selectors might have had a few words of praise for the man who changed the course of a match and a series and recorded what were then the sixth best bowling figues in Test history. Not a bit of it – this is what the old curmudgeon had to say The trouble with Devon is that he does not have a natural-length ball. That is why he goes for so many, because you cannot set attacking fields for someone like that. His control so often deteriorates when he goes wide of the crease, and he cannot then bowl a consistent line. At times, he must drive his captain spare, because just when you are prepared to forget him, he clicks for a few overs, and has the sort of game he had at the Oval

After having played just one Test in each of England’s last four series Malcolm’s heroics at least ensured he palyed in four of the five Tests of the ill-fated 1994/95 Ashes series, the main highlight of which, on a personal level, was his innings at Sydney already referred to. His 13 wickets cost more than 45 runs each. He did take seven in England’s consolation victory in the fourth Test, although in truth it was a match thrown away by an over-confident Australia, who decided to have a go at scoring 263 in 67 overs when, all factors considered, they really should have settled for the draw.

Malcolm’s 1995 was much like his 1994. He played in the first Test against West Indies, and took a couple of wickets, was then dropped and came back for the final Test at the Oval. There were three wickets then, in the visitors mammoth 692-8, but they cost 160 runs and it was doubtless as much for psychological reasons as any confidence in his ability on Illingworth’s part, that saw Malcolm in the squad for the winter tour to South Africa. Even then Illingworth made it clear to him that he would be expected to work with bowling coach Peter Lever on his action.

In September 1995 Malcolm underwent keyhole surgery to sort out a knee problem that had troubled him on and off for some time. Understandably he was a little way from full fitness when he arrived in South Africa and was, as a result, not entirely receptive to Lever’s desire to tinker with an action that he felt had served him well for over a decade. It did not help that Lever seems not to have been entirely clear about what was expected of Malcolm beyond an attempt to replicate what Lever thought was a subtlely different action that Malcolm had used to produce the delivery that dismissed Carl Hooper at Headingley the previous summer, with the first delivery of the West Indies first innings.

Matters initially came to a head after Malcolm was told by Illingworth to report to Centurion Park to work with Lever before the conclusion of the first ever First Class match to be played at the Soweto Oval. That was followed by a press conference at which Illingworth openly criticised Malcolm, leaving the Derbyshire bowler incensed at this very public questioning of his abilities. The mutual antipathy between the two was crystal clear for the rest of the tour and came to a head at the end of the final Test. Malcolm had played in the second Test, which had been dominated by and is remembered today because of Michael Atherton’s remarkable match-saving innings of 185*, but Malcolm took six wickets and played his part. That wasn’t enough to keep his place in the next two Tests, two more draws, and after not having played in anger for almost a month it was a major surprise when Malcolm was recalled for the final match at Newlands. England won the toss and batted and capitulated meekly for 153. The bowlers nearly pulled it back for them, reducing South Africa to 171-9 with just Paul Adams to come. At that stage of his career Adams batting was probably inferior even to Malcolm’s, and Devon was brought back to finish him off with a straight one. In the event there was a Chinese cut for four, overthrows to the boundary from a shy at the stumps, and a rare four byes through Russell amongst other misfortunes, and the last pair added 73 crucial runs. With England’s batsmen again letting themselves down, all out for 157 this time, South Africa had a comfortable ten wicket victory with which to take the series. After the game an angry Illingworth stormed into the England dressing room and rounded on Malcolm, holding him solely responsible for the defeat. To Malcolm’s credit he did not react then, but on his return to England began a war of words in the press, giving vent to the frustrations that had built up over the duration of the tour. Illingworth responded in kind and an unseemly spat followed.

Lawyers were busy and, eventually, a statement was cobbled together by the two sides that laid matters to rest. Despite his breaches of contract, committed by virtue of what was published in his name, Malcolm avoided censure. Illingworth did not, initially at least, get away quite so lightly as he was fined GBP2,000, but that was eventually quashed. Illingworth left his job at the end of the 1996 season and, inevitably, Malcolm was not selected for that summer’s series against Pakistan and India, and he spent his time taking 82 wickets, his best ever haul for them, for Derbyshire.

In 1997 the Australians were back again. They were greeted by a new Chairman of Selectors, David Graveney, and a false dawn. England, with Malcolm getting two wickets, reduced Australia to 54-8 and then 118 all out on the first morning, and won the first Test by 9 wickets. They won the sixth Test as well, but having been thumped in the third, fourth and fifth it mattered little. Malcom started four of the Tests, his final England appearances, but had just six wickets at 51 runs each to show for his labours. If that seemed scant reward for a lot of effort he did at least have the consolation of a bumper benefit that netted him GBP300,000.

Despite that handsome sum the Derbyshire dressing and committee rooms were not happy places in 1997 and in the winter Malcolm moved to Northamptonshire. He was approaching his 35th birthday and, for a fast bowler, was already pretty long in the tooth and didn’t want to remain with a county that was rapidly losing its heart. There was some bitterness on the part of those who saw him as making a run for it after feathering his nest, but that was inevitable in the circumstances and anyone reading Malcolm’s own account of what happened will have considerable sympathy for him.

Malcolm served Northamptonshire well for two seasons, and indeed in 2000 he started the season reasonably well, but was then dropped as the county decided to play an extra batsman. Perhaps surprisingly the aging paceman then found another county, Leicestershire, and he gave them two good seasons too before, in 2003 Anno Domini, and more particularly that troublesome knee, finally caught up with him and, a few months into his fifth decade, the end came. He had still been decidedly quick in his last few seasons, and had recorded a match-winning ten wicket haul against Yorkshire as recently as June 2002.

Devon Malcolm’s Test career consisted of 40 appearances, in which he took 128 wickets at a cost of 37 runs each. They are not the sort of figures to excite the game’s statisticians, and do nothing to dispel the commonly held belief that while Malcolm could be distinctly fast his lack of control made him an expensive and unreliable luxury. But he seems to have been a man who was more appreciated by his opponents than by his teammates. In 1988 a 21 year old Alan Donald, playing for Warwickshire, had a good look at Malcolm and concluded He wasn’t just a muscular fast bowler, he’d glide into the crease on his toes, with lovely rhythm. In comparison I was very flat-footed and was unable to generate a balanced run-up … so I copied him ….. it worked. Tellingly Donald also highlighted the obvious reason for Malcolm’s relative failure at the highest level; Devon never seemed to be trusted by the England hierarchy, who didn’t appear to understand the mentality of the fast bowler, his need to be supported and tolerated when things weren’t going well.

But Devon was always popular with England supporters, even if he could be frustrating, and no one who saw it will ever forget that 9-57. As to an epitaph on his cricketing career I have no doubt at all as to what he would choose as his favourite, and for me too it is the most appropriate I have read. It came at the end of October 1995 when, in Soweto, Malcolm was introduced to Nelson Mandela, whose greeting to him was I know you, you’re The Destroyer.

nice writeup. could have had quite a career, if not for australia

Comment by uvelocity | 12:00am BST 29 July 2012

that was an awesome bowling

Comment by wolfeye | 12:00am BST 1 August 2012

Nice article, Martin. I think it was Mark Waugh who said that Malcolm was the quickest he ever faced. I remember Dujon’s dismissal in either the Jamaica or Port of Spain Test in 1990, too. His expression was one of utter shock as Devon so obviously beat him for sheer speed, knocking out his off stump.

Comment by garethb | 12:00am BST 1 August 2012