The Dirt in the Pocket Affair

Martin Chandler |

The third and final Test between England and South Africa in 1965 might have gone down in history in spectacular fashion. South Africa led the three match series 1-0 and had left England to score 399 to win in the fourth innings. Bradman’s Invincibles had successfully chased down 404 at Headingley in 1948, ridiculously for the loss of only three wickets, but that apart the next highest fourth innings chase was 336, and England’s best 332. At the Oval England ended up on 308-4 with Colin Cowdrey well set on 78, and skipper Mike Smith on 10 when, with 71 minutes to go the heavens opened and ended the game.

The winds of change had started to blow around the sporting world in 1965, but no one watching that game would seriously have believed that the next time the two nations would meet in a Test would be 29 years later, but so it proved to be, and it was not until July 1994 that a South African side led by Kepler Wessels met Mike Atherton’s England at Lord’s. It was a momentous occasion with a variety of interesting and unusual spectators attending at various stages of the match, most notably perhaps Peter Hain, who had done so much to bring about South Africa’s initial isolation, and iconic activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Wessels scored a century in the match and was well supported by the rest of his batsmen. Alan Donald and the rest of the South African pace attack bowled superbly, and the visitors victory margin was the small matter of 356 runs. The match is seldom remembered for that though. It is the notorious “dirt in pocket” incident that is almost always the reason when the game is mentioned now.

In order to fully appreciate what happened it is necessary to tell the story of what occurred as it unfolded on the third afternoon of the game. The match situation was that South Africa had won the toss, batted and compiled a first innings of 357. England’s response was a disappointing 180 and by the middle session of that fateful Saturday the weather was hot, conditions were humid and, the ball steadfastly refusing to provide any of the England bowlers with any sort of sideways movement, South Africa went steadily about building their matchwinning lead.

Being Saturday afternoon, in those days the BBC coverage was such that airtime was split between the Test and a race meeting at Ascot. For that reason when the cameras first picked up Atherton putting his hand in his pocket before rubbing the ball the only audience that saw the pictures were in South Africa. The local broadcaster there was swamped with calls and a little later a similar incident took place in front of English viewers. On the back of what had been captured the commentary and press boxes were buzzing.

After the close of play Match Referee Peter Burge summoned Atherton and coach Keith Fletcher to a meeting. Also present were the two on-field umpires, the legendary Harold “Dickie” Bird and Australian Steve Randell, as well as TV umpire Merv Kitchen. The meeting lasted two hours, but the waiting journalists were to be disappointed as all they got that evening was a statement from Burge to the effect that he had investigated Atherton’s unfamiliar action, was happy with the explanation that he had received, and that he would be taking no further action.

Next day Wessels declared 455 runs to the good, and England capitualted for just 99 to give the South Africans their huge victory. A press conference was announced for that evening where it was said that Atherton would explain all.

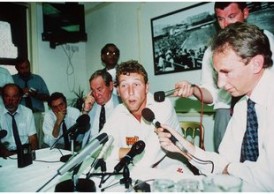

Atherton, sat with Chairman of Selectors Ray Illingworth, read a prepared statement. He explained what sweat was used for in terms of looking after the old ball, and went on to say that what he had been seen doing on camera was drying his fingers with the dirt in order to keep his hands dry when handling the ball. He admitted that he had not told Burge the whole truth the previous evening, as he had omitted mentioning he had actually had dirt in his pocket.

Illingworth then had his say and confirmed that in respect of two matters Atherton had been fined GBP2,000, those being for using dirt to dry his fingers, and for being less than totally frank with the Match Referee. Jonathan Agnew then asked Atherton twice whether the dirt in his pocket had got on to the ball. He said unequivocally that it had not. The interview, which all concerned have described as having taken place in an extremely hot, airless and uncomfortable room, was broadcast live on Sunday Grandstand, although it seems no one had told any of the participants that that would be the case.

At this point it is worth pausing to look at Law 42(5), as it then was, which read Any member of the fielding side may polish the ball provided ….. no artificial substance is used. No one shall rub the ball on the ground or use any artificial substance or take any other action to alter the condition of the ball …… this law does not prevent a member of the fielding side from drying a wet ball.

Something else that Atherton said in the press conference was that because the weather was so dry, it should have been possible to get the ball to reverse, and in Craig White and Darren Gough England had two particularly skilled exponents of that art. Reverse swing does require the roughed up side of the ball to be kept as dry as possible. So Atherton’s account of his reasoning does make perfect sense.

Had Atherton tampered with the ball or not? He had said little but what he had said amounted to a firm denial and that might have been that had not some more footage, that originally seen only in South Africa, then become available, which clearly demonstrated that what Atherton had said to Agnew was not correct, and that dirt had been placed on the ball. This earlier footage was therefore rather clearer than that which had been seen in the UK.

The first point to be made is that there is without doubt no rule that prevents a cricketer using dirt to dry his hands if he so wishes. The first part of Atherton’s fine was therefore in respect of an action that quite simply was not against the rules of the game. Why was it therefore imposed with such alacrity? The answer to that is, presumably, in an effort to put the whole controversy to bed as quickly as possible.

Is dirt, soil or whatever you wish to describe it as an artificial substance? A definition of artificial that I consider non-controversial is humanly contrived, often on a natural model. Now this is where things get tricky. Every fibre of my being screams at me that dirt is a naturally occurring substance and that any suggestion to the contrary is patently absurd. But then I remember my legal training, and reading Atherton’s explanation that the dirt in his pocket came from one of the old wickets on the square. Now I am no groundsman, but I do know the barest minimum about substances such as “marl” and “loam”, and that the preparation of a cricket wicket owes something to the arts of the alchemist, so it must be possible to argue with considerable force that dirt that comes from a cricket wicket is too far removed from natural soil to be considered as anything other than artificial.

The truth of the matter is that whoever drafted the 1980 code of the laws, as updated in 1992, did not really give much information. When interpreting statute law you always start off by giving words their “ordinary and natural meaning”, or more concisely the “Literal Rule”. Words are not however always quite as clear in their meaning as lawyers would like. So there is something called the “Golden Rule” which can be used to avoid otherwise absurd results that literal meanings might give rise to. There is the “Mischief Rule” which, when applicable, can mean that the purpose of the law can be looked at in order to clear up uncertainty or ambiguity. Another aid to interpretation is the “Ejusdem Generis” rule which can apply when, unlike here, there are lists of words, in light of which others need to be interpreted. And then there is one more that is not officially recognised, but all half-decent lawyers try it sometimes, and I did in my previous paragraph. As I say it doesn’t have a name, so I shall christen it – I will call it the “Specious Bollocks” rule, and trust I do not need to elaborate further.

Thus in my view all that Atherton did was polish the ball using a substance that occurs naturally on a cricket ground, and therefore he did not transgress the laws of the game in any way at all. So how did a not inconsiderable section of the media decide that he had committed an offence worthy of being stripped of the captaincy and hung out to dry? The first possibility is his, on his own admission and beyond any doubt, being a little less than candid with the Match Referee. His explanation for that was panic, and to my mind that is a perfectly acceptable explanation. Before Burge turned to him he had already heard both umpires confirm that their regular inspections of the ball had given no cause for concern whatsoever. So why on earth should he, without having had the benefit of properly considering his position, have answered any questions at all? The potential sanction for ball tampering was so far reaching that it seems to me that were the same situation to arise today there would be compelling Human Rights arguments as to why he should not have been interviewed at all at the point in time that he was, with no disclosure of the case against him, and without an opportunity to properly consider his position with the benefit of legal advice.

The other possibility is that he was indeed guilty of ball tampering, and this is the accusation that Agnew levelled at him. Aggers seized on the part of Law 42(5) which expressly forbids the rubbing of the ball on the ground. By implication, argues Aggers, that must mean that rubbing the ground on the ball is just as illegal. Do you see what he did there? I certainly do and I take my hat off to him because that is, if anything, a rather better example of the “Specious Bollocks” rule than my own. It’s a bit (and yes I am being somewhat flippant here) like saying if it is in order to hold a ball in such a way that a drop of rain falls on it, then by implication it must be lawful to dunk it in a glass of tap water at the drinks interval.

Once Agnew saw the “South African” footage he became convinced that the issue was one which required Atherton to fall on his sword and resign. In fairness to him he must have been irritated by the fact that Atherton had been less than truthful with him at the initial press conference after the match ended, but he still seems to have shown a total lack of understanding of the pressures that the England captain had been under. I have only ever observed or heard Atherton from a distance, whereas Agnew had the benefit of knowing him, but while I could and can appreciate that Atherton might not have been the most likeable or approachable man in the game back in 1994, his integrity has never been in question as far as I am concerned.

And this story was all over the press, and not just the back pages. There was a huge amount of interest in it and it must have been obvious to Agnew, as BBC cricket correspondent, just how much influence he could exert. He was interviewed on unfamiliar territory, on the main evening news, and his views reached a much wider audience than would normally have been the case. He did not hold back.

The press went to town on poor old Atherton. The Daily Mirror’s headline was simple in the extreme, Go. The Sun preferred two words, Quit Now. But it wasn’t just the gutter press that jumped on the Agnew bandwagon. The Times’ headline was Atherton fined GBP2,000 over “dirty tricks”. Its leader thundered If the captain of England’s cricket team fails to uphold the values of his society – or the values to which his society aspires – he is unworthy of that uncommon honour which the captaincy represents. In the middle ground the long defunct Today told its readers He has dithered and obfuscated and what bits of truth we know have been dragged out of him through TV evidence, and Agnew himself contributed a column to the Daily Express under the unattractively sensationalist headline Why Atherton has to go.

Not surprisingly Atherton thought long and hard about his position but, in truth, was supported by many whose opinions he doubtless valued more than those of his detractors. Former England teammate Derek Pringle said As any ball tamperer worth his salt knows, these are not the actions of somebody who is wilfully trying to alter the condition of the ball; his touch is too light. Respected Ashes opponent Alan Border was dismissive when asked his view It’s a storm in a teacup, a media beat-up that is making it seem a lot worse than it deserves., and of course whatever side one took on the basic question, the existence of a media feeding frenzy could not be disputed. Another playing contemporary, Mark Nicholas, clearly disapproved of the adverse coverage and wrote; This small, silly error was blown out of all proportion by the prying camera and by the hysterical clamouring for the head of a man who has carried our beloved, if limping, cricket team through a blisteringly difficult year.. From a bygone era fellow Lancastrian Brian Statham, a former professional but a true gentleman in every other sense of the word, expressed the view You constantly get bowlers rubbing their hands in the dust, so a little dust in the pocket shouldn’t matter that much.

As for the South Africans Alan Donald described the incident as A relatively minor matter. Journalist Colin Bryden made the most telling point; From our point of view the saddest thing is that the Atherton controversy has overshadowed the result

John Thicknesse in the Evening Standard raised an important observation in quoting the former Pakistan captain, Asif Iqbal, who said The Pakistanis were branded cheats on far less visual evidence than has been produced in Atherton’s case. Ball tampering was seen as the game’s greatest evil at the time, and there were many who still did not believe in reverse swing, and were convinced that Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis and Aqib Javed had “got away with it” just a couple of years before. For some therefore Atherton no doubt looked like an appropriate sacrificial lamb.

But the press themselves were far from universally behind the Agnew view. Atherton’s future employers, The Daily Telegraph, remained behind him and printed a letter from the Reverend Andrew Wingfield-Digby who, despite having very recently been dismissed from his position as team chaplain, compared The media hacks of today with The scribes and Pharisees of Jesus’s time. The respected Daily Mail journalist, veteran Ian Wooldridge, raged My trade does a good job from time to time, but the Atherton episode was disgraceful. A man’s career, life and reputation were on the line and so few, in the rush of instant journalism, gave a damn.

In the Mail on Sunday Patrick Collins was particularly scathing towards Agnew who, to be fair to him, did quote this passage in his 1997 autobiography “Over to you Aggers”, although having introduced the relevant chapter with it thereafter he seemed essentially unrepentent. Collins’ word were Jonathan Agnew, the cricket correspondent of the BBC, has issued a demand for the head of the England captain. Pity about Aggers. A distinguished cricketer, a fine broadcaster and an engaging companion, he managed to sound like the resident prig of the Lower Fifth with an abjectly pompous performance.

The perfect riposte for Atherton would have been a century in the second Test. Sadly he couldn’t quite deliver, but 99 in the first innings underlined his strength of character. That game was drawn but, in the third and final Test at the Oval, Devon Malcolm’s remarkable 9-57 squared the series. What should be remembered by all as the highlight of Atherton’s career also involved South Africa, as took he took the best part of 11 hours to bat his side to safety at the New Wanderers in December 1995. As for the “Dirt in the Pocket” affair that, to use the words of the immortal bard, was “Much Ado about Nothing”, and history should view it accordingly.

Cracking read Fred.

Comment by GIMH | 12:00am BST 23 July 2012

Brilliant, again.

Comment by Uppercut | 12:00am BST 23 July 2012

fascinating read..The author has focused on the “artificial” substance aspect and exonerated Atherton but what about this line in the law [B]”or take any other action to alter the condition of the ball”[/B]..

Comment by doesitmatter | 12:00am BST 24 July 2012