The Dutchman and the Avalanche

Martin Chandler |

Most Test cricketers, and indeed First Class players, make their talents obvious from an early age and soon leave their peers behind. Peter Heine and Neil Adcock had much in common, including the fact that they did not fit that stereotype. This formidable pair of South African fast bowlers, who caused as much discomfort to the batsmen who faced them as any in the history of the game, gave no early warning of what was to come.

Heine was the senior man, by almost three years, and of Dutch ancestry. He played very little cricket until, aged 19, he was persuaded during his employment as a fire officer to play for the works team. On the basis of his build he was invited to open the bowling. From that standing start he was playing First Class cricket in just over four years.

Adcock on the other hand did play the game as a schoolboy, and reasonably well, but he was no prodigy, bowling medium pace for his school second XI. It was only in the 1951/52 season, by which time he was already 20 years old, and he was given the opportunity to play in a club trial match under the captaincy of Test star Eric Rowan, that he started to speed up, and make real progress.

Having been set on the right path the impact that Adcock made was such that within two years he had forced his way into the Test side against the touring 1953/54 New Zealanders. After a quiet time in the first Test he made his reputation in South Africa’s comfortable victory in the second Test that began on Christmas Eve. The match was played at Ellis Park in Johannesburg. There was a gap between the closure of the Old Wanderers stadium in the city, compulsorily acquired for the building of a railway station, and the opening of the New Wanderers in 1956/57, so for three series the Rugby Union stadium was used for Test matches twice each season. It was a happy hunting ground for fast bowlers and Adcock took full advantage. This was the game that is best remembered for the bravery of Bert Sutcliffe who, after receiving a sickening blow on the head from an Adcock delivery, went back into bat after a hospital visit found no fractures, and scored an aggressive and unbeaten 80. Equally well known is that in the course of that innings Sutcliffe added 33 precious runs for the last wicket with Bob Blair, who had just learned that his fiancee had been killed in the Tangiwai Rail Disaster on Christmas Eve.

New Zealand all-rounder Eric Dempster described Adcock as truly ferocious. John Beck, not yet 20 years old and a man did not make his First Class debut until after the party arrived in South Africa, batted bravely for almost an hour at Ellis Park, and said many years later what an introduction to my first Test. Balls from Adcock shaving and hitting heads, rearing from a good length, our batsmen being helped from the field bleeding and battered. As well as Sutcliffe Lawrie Miller was badly hurt, coughing blood when hit on the chest, but all the recognised batsmen were repeatedly struck. And it certainly wasn’t a case of the visitors complaining just because they were beaten. Only last year in his autobiography the South African batsman Clive van Ryneveld wrote Adcock’s bowling was lethal, rising sharply and hitting gloves and body frequently.

As a result of his efforts in that first series Adcock earned the soubriquet Avalanche. South Africa won 4-0 and Adcock took 24 wickets at 20 apiece. Fortunately for the tourists Heine was not selected for any of the Tests, and after his one appearance against them when playing for Orange Free State brought him match figures of 11-60, they were doubtless much relieved about that.

All bar one of Heine’s Tests came in the series in England in 1955, and then the next two at home, against Peter May’s England in 1956/57 and, in the following season, against Australia. England were as strong as they have ever been in the mid 1950s and those two series against the South Africans were amongst the most competitive and compelling in the history of the game. In 1955 England won the first two Tests, only for their visitors to win the next two to set up a thrilling finale at the Oval which, after being bowled out in their first innings for just 151, England turned around to win and take the series. It was much the same in the return back in South Africa with England taking a comfortable 2-0 lead before the tide turned. An engrossing third Test was left drawn with South Africa 48 short of victory with four wickets in hand. The home side then took the fourth and fifth Tests to square the series.

After those performances and, given the then domination of Australia by England, it was expected that the South Africans would brush the Aussies aside in 1957/58. In the event it was a comfortable 3-0 win to Australia and with the retirement of Heine after just two Currie Cup games of the 1958/59 season a chapter in the history of South African cricket closed.

Of the 15 matches covered by those three series Heine missed the first Test in 1955, and the second in 1957/58. Adcock played in all but the fifth Test in 1955 although, having broken down in the fourth after bowling just four overs, he effectively missed that as well. In the 12 Tests that the pair played together they took 97 wickets between them at a cost of just 22 runs each.

After the comments of Dempster and Beck that I have already quoted it will perhaps come as a surprise to learn that Heine, who Jim Laker dubbed The Bloody Dutchman was even meaner and nastier than Adcock. He made an immediate impression on debut at Lord’s, May describing an early delivery to England opener Don Kenyon thus; Don pushed sedately forward to a good length ball which kicked and, as the saying goes, almost parted his hair. Tom Graveney was at the other end when that frightening delivery was bowled and for him Heine quickly established himself among the four best fast bowlers I have ever played against.

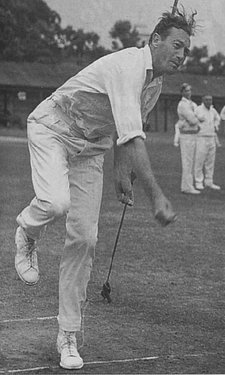

As to Heine the man Laker wrote He was a fearsome figure, his black hair straggling over his eyes and a great red streak across the front of his shirt, on which he viciously polished the ball. Years later Graveney commented I was never sure what was his main interest in life – hitting the stumps or knocking batsman over … he kept coming at you from a short length as if he were trying to bully you into error.

There are, inevitably, some famous and well-worn stories. In 1956/57 Heine felled England opener Peter Richardson with a bouncer and glared at him as he lay on the wicket and snarled get up – I want to knock you down again. By way of further confirmation of his character Laker commented …his attitude to the job was simple. He bowled at the batsman as often as he bowled at the wicket. Although Bailey himself made no complaint of the incident Laker would also tell a story about an animated Heine warning that most obdurate of all-rounders, I want to hit you, Bailey ….. I want to hit you over the heart. Why didn’t Bailey complain? He was as hard as nails of course and, at the time, he was taking guard a yard outside his crease in order to disrupt Heine’s length – I would think he was far too busy taking pleasure in having succeeded in his ploy than worrying about the occasional threat.

But if Heine was the bogeyman Adcock lost little or nothing in comparison. South African journalist Charles Fortune said of him Adcock in action is the very picture of what a fast bowler should be. His entire action is beautiful to behold and his pace a shade hotter than that of his contemporaries. From the perspective of an England batsman Graveney wrote; Somebody remarked once that arm bowlers could not be really fast. Well, he (Adcock) was as near to being an arm bowler as anyone I have ever seen, and he was decidedly quick. Adcock’s teammate and sometime captain Jackie McGlew had this to say in his autobiography; Adcock I must rate, technically, as the finest new-ball bowler produced in South Africa during my career. He had the priceless asset of extracting pace and disconcerting lift from the most lifeless of pitches.

Both men could swing the ball as well, although that tended to be a lesser threat, as pitching the ball up was not the length of choice for either.

Of the two as a pair May wrote in retirement, remembering his first encounter with them; The 6 feet 4 inch Heine, and the rather wirier Neil Adcock were to prove a formidable combination of fast bowlers over the next two years……… they were at you all the time, banging the ball into the pitch at a genuine fast pace. English journalist EW “Jim” Swanton took the view that never before had South Africa mounted a fast attack equal to that of Heine and Adcock. Graveney was a little more pragmatic; As a pair they may not have been the most gifted, but they were certainly the nastiest. If they could see that they were creating a bit of panic up your end of the pitch, then they were happy.

Colin McDonald opened the batting for Australia in 1957/58 and although he averaged more than 43 for the series he had a torrid time against the opening salvos of both bowlers. Ever the gentleman he suggested in his 2010 autobiography that; Perhaps they represented an early manifestation of the constant sledging or, more politely, mental disintegration, which has arisen in cricket some fifty years later. A few years previously Richie Benaud had been rather more blunt, describing Heine as one of the greatest sledgers of all time.

Why did South Africa lose so badly in 1957/58? Based on what happened to the recently mighty England team in Australia in 1958/59 it is pretty clear that they were simply outplayed and outthought by the better team although, certainly at the time, it seems unlikely that Heine and Adcock would have agreed. South Africa had a new skipper after the first Test, Van Ryneveld, and he tried to restrict his spearheads to just one bouncer in each eight ball over. Heine and Adcock generally toed that line until right at the end of the series. Australia just needed 68 to wrap up the 3-0 victory. They got there easily enough in the end but not before having to face what Fortune described as the most terrifying eruption of fast bowling I have ever seen …. Heine and Adcock between them sent down seven overs of electrifying pace and soaring trajectory.

In one over Adcock send down three consecutive bouncers at McDonald. Van Ryneveld and the umpires spoke to him. Whatever may have been said was ignored as the next delivery was another bouncer and it caught the edge and McDonald was gone. McGlew thought it was the fastest over he had ever seen delivered, and McDonald later confided in him that it was the most frightening he had ever faced. When “CC” got back to the safety of the dressing room he was understandably furious and deeply critical of the bowling. It is said that what he overheard inspired a young dressing room attendant to want to bowl just like Adcock. As for Heine and Adcock, firm friends off the field as well as partners on it, they were deeply unhappy at having the use of their main weapon rationed in the way that it was. With the benefit of more than 50 years to reflect on his tactics Van Ryneveld was inclined to concede the point in his autobiography. Having quoted Fortune as describing his fast bowlers a few hours after the match finished as …very stroppy and quite unrepentant. he added, on the subject of bumpers, In retrospect we could legitimately have used more.

South Africa’s next series was in England in 1960 but to the relief of the home batsmen the fearsome duo had been broken up by Heine’s retirement, and they would have been forgiven for hoping that his recent chequered history with injuries would have reduced the threat that Adcock posed. For their part the South Africans had high hopes of the partnership that Adcock, now 29, might forge with 20 year old Geoff Griffin. The youngster’s career cruelly ended at Lord’s when he was no-balled for throwing. South Africa lost this series 3-0 as well and there was some discord in the party once it became known that the management were not going to call for Heine as a replacement, his change of heart about his retirement and availability not impressing the South African selectors. There was however no blame to be attached to Adcock, who took 26 wickets in the series at 22 and, on the tour as a whole, 108 at just 14. He was named as one of Wisden’s Five Cricketers of the Year in 1961. The accompanying article, commenting on his success in 1960 said; Even Adcock himself was surprised at his new-found ability and enduring stamina. He believed that the chief reasons for his success lay in his acquisition of a smooth rhythmic action which put a minimum tax on his energy, and in his building-up exercises. Unlike many fast bowlers Adcock does not employ a pronounced movement of the body at the point of delivery. He bowls without interruption in the course of his run, swinging his arm on a trunk that is virtually upright – like a sudden gust turning a light windmill.

In 1961/62 New Zealand visited South Africa for a five Test series. The Kiwis had only ever won a Test against any opposition once before, and that had been a consolation victory in a series five years previously that they had lost 4-1 at home to West Indies. The home side began the series as overwhelming favourites. As things turned out the series was highly competitive and had it not been for a six wicket haul from the former dressing room attendant making his Test debut, Peter Pollock, as New Zealand chased a modest 197 for victory in the first Test, South Africa would have lost not only that match but the series as well.

Due to injury the 29 year old Adcock did not play in the first three Tests. In the second, a draw, there was some controversy as at the close of the final day when, with nothing left to be gained, Pollock let go a stream of bouncers in the final over. He was “rested” as a result and New Zealand won the third Test. Home skipper McGlew was furious. It had been his instruction to Pollock to bowl the bumpers that cost him his place and to compound his anger at the decision to drop the youngster New Zealand had then subjected his team to a barrage of short-pitched bowling themselves, which he was powerless to respond to as the selectors had not given him a fast bowler.

McGlew wanted all three of Heine, Adcock and Pollock in the team for the fourth Test. He didn’t get his way with Pollock, but the old firm was reunited for what was to prove to be one last hurrah. New Zealand skipper Reid won the toss and chose to bat. It was the wrong decision and the Kiwis were dismissed for 164. Heine went wicketless and there were just two for Adcock who, it was noted in Wisden, was some way below his usual pace. Reid top-scored with 60 and after South Africa’s matchwinning 464, in the losing cause of New Zealand’s second innings he blazed his way to 142 out of 249, one of the great Test innings. Reid chose to rile Heine and the bowler let loose plenty of invective in his direction as a result. Reid made his displeasure known.

Heine took a couple of wickets in the second innings including, eventually, that of Reid but it was not a great way to finish his career. He found himself dropped for the final Test by virtue of his overdoing his sledging of Reid, paving the way for Pollock’s return. In the final Test there were six wickets for Pollock and four for Adcock but South Africa’s batting, despite being assisted by a ninth wicket stand of 60 by their two fast bowlers, ended up 40 runs adrift of New Zealand who, thanks in large part to a fine all-round performance from Reid, squared the series against all expectations.

The psychological battle had been won fairly and squarely by Reid – he had come across to the South Africans as a whinger, constantly complaining about their fast bowlers. The reality was however that he desperately wanted the South African quicks fired up and playing in the team. He was a fine player of fast bowling as his record in the series amply demonstrated. What Reid didn’t like was spin bowling, and although it was five years since he had enjoyed any sustained success, the last thing that Reid wanted was a recall for the great South African off-spinner Hugh Tayfield, still only 33 years of age, who had troubled him greatly in the past.

It looked for some time as if Heine’s final First Class appearance would be that Test against New Zealand but, in somewhat unusual circumstances, there was in fact to be one more. After he left the First Class game Heine gave up cricket, and took to golf for his recreation. He sold beer for a living and, not for the first time amongst former sportsmen who occupy themselves in that trade in retirement, he put on a lot of weight. When England next toured the Veld, in 1964/65, there was a two day match arranged early in the tour between the tourists and a Transvaal Country Districts XI. Heine fancied a tilt at the old enemy so he joined the Potchefstroom Club and worked on his bowling and the extra timber to such effect that 30 pounds dropped off him. He duly gained selection although hopes of rekindling the glory days were dashed as, while not bowling badly, he went wicketless as the tourists got to 337-5 before declaring. With the part-timers 94-6 in their second innings, still 136 behind, an easy victory beckoned until Heine, who had never scored more than 67 against First Class opposition before, scored a very rapid 108 to enable the home side to draw the match.

When the tourists lined up against the full Transvaal side two days later they unexpectedly found themselves up against Heine again, but there was no mistake this time as they did win by an innings. There was no matchsaving knock from the veteran quick bowler this time, but he did take 5-110 in the tourists’ 464-9 declared and was the home side’s best bowler. He was pretty quick, and moved the ball around, but the extra lift from a good length that used to cause top class batsmen to have sleepless nights, was no more. There was also some controversy too, as England skipper MJK Smith objected to Heine coming back on the field to take the second new ball after an hour in the pavilion with a supposed leg strain. His point made Smith relented and, his tail doubtless now up, Heine rounded off his First Class cricketing duties with three quick wickets before the declaration. That game over if there were further opportunities offered they weren’t accepted, and Heine returned to the golf course. He died, in his 77th year, in 2005.

For Adcock as well the New Zealand series was just about the end. He followed the Kiwis home as a member of a strong International XI that played a series of three matches in New Zealand and the following season he ended his career with five Currie Cup games for Natal. He only took 11 wickets, but paid less than 20 runs each for them. After breaking down in the penultimate match he missed the final game of the season and, despite having only just turned 32, he did not return. Neil Adcock eventually earned his living as a commentator and is still with us, having recently celebrated his 81st birthday*.

There have been some fine pairs of opening bowlers for South Africa since the 1950s. The next pair, sadly unfulfilled, were Pollock and Procter, and their natural successors, Procter and Van der Bijl, never played so much as a single Test. Since readmission we have seen Donald and De Villiers, Pollock and Ntini, and Steyn and Morkel, but none have quite the same ring as Heine and Adcock nor, in my view anyway, have any of them been quite as intimidating.

*This feature first appeared in June 2012. Adcock passed away 6 months later.

What a great article.

Comment by Marius | 12:00am BST 13 June 2012

Fantastic article, fred.

Also, Charles Fortune, WAG

Comment by Quaggas | 12:00am BST 13 June 2012