19-90

Martin Chandler |

In 1956 the 22nd Australian touring team arrived in England. They were by no means the strongest side to visit the northern hemisphere, and England had won the previous two series, in 1953 by just shading an even contest, but convincingly in 1954/55. That said nobody in England underestimated the team that Ian Johnson captained, The Cricketer, in its preview of the tour pointing out that there were only two great batsmen on show, Peter May and Neil Harvey, and that with English conditions bound to draw Frank Tyson’s sting, the aging Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall would be the better pace attack. The battle of the batting greats was won easily by England skipper May, who averaged 90 for the series as against Harvey’s 19. In fact Australia’s batting as a whole was woeful, only Jim Burke averaging more than 30, and then by just a whisker.

In an era when it was generally assumed, with a degree of justification, that Australians could only give of their best on hard, fast and bouncy wickets the visitors were not helped by the summer being one of the wettest on record. There were 43 days of cricket on the tour that were curtailed by rain and/or bad light 13 of which were completely blank. The Australians were also hampered by playing conditions in England that differed markedly from those that they encountered at home. Since the 1950/51 series Australian pitches, in the event of rain, were completely covered. In England only the bowlers’ run-ups were covered and, once a match was underway, those covers could at no time protrude more than 3.5 feet over the popping crease, even at night.

The above having been noted the Australian party did have plenty of English experience and, in the manner of Test tours of that time, had ten First Class matches before the first Test. Those matches were treated as practice matches by Johnson, and only two were won. Unusually one was lost as well, Surrey hammering the tourists at Kennington Oval by ten wickets. Off spinner Jim Laker sensationally took 10-88 in the Australian first innings.

Laker had not even merited a mention in the tour preview in The Cricketer that I have already referred to. He had turned 34 in the previous close season and was not necessarily expected to figure in the Test side. At that stage in his career he had played in 24 Tests and had taken 86 wickets at 28. Since his home debut in 1948 he had never played a full series in England, and after a disappointing tour of the Caribbean in 1953/54 he had played just once against the 1954 Pakistanis and, in 1955, until he was recalled for the final Test at the Oval, did not figure in the series against South Africa. For their off spinner in 1954/55, not that he got a lot of work, the selectors turned to Glamorgan’s Jim McConnon. Without that ten-for it would have been by no means certain that Laker would have been selected for the first Test at Trent Bridge.

Rain spoiled the Nottingham Test but it set the tone for the series. England, thanks to their captain and Peter Richardson, got to 217-8 before closing their first innings. Their opening attack of Alan Moss and Trevor Bailey then bowled just seven overs between them before Laker and county colleague Tony Lock, he of the orthodox left arm spin with a decidedly unorthodox action, with a little help from Yorkshire medium pacer Bob Appleyard, shot Australia out for 148. The same bowlers threatened to run riot again in the visitors’ second innings, but after the loss of three quick wickets Burke and Peter Burge put up the shutters and, in the end, comfortably batted out time.

For the second Test at Lord’s the Australians were greeted by the best weather they saw all summer and, for the only time in his Test career, Miller grabbed a ten wicket haul. When Australia batted Richie Benaud, from number eight, pulled their second innings round with a fine 97, scored out of 117 added for the seventh wicket with “Slasher” Mackay. Benaud was eventually out going for another big hit for his century, but by then Australia had more than enough to see off England and they duly completed a 185 run victory.

England were worried about their batting after Lord’s and the decision was made to omit Tom Graveney and Willie Watson for the third Test at Headingley. At that point three of the selectors, Gubby Allen, Wilf Wooller and Les Ames, told the fourth of their number, Cyril Washbrook, to go and get the drinks. Washbrook was 41 and had not played for England for more than five years but, by the time he returned, Allen told him that the decision had been made that he was playing. It was not a unanimous decision, skipper May’s objections being overruled.

Luck can play a huge part in the game of cricket and that can never be as well illustrated as it was at Headingley. Ron Archer sent Richardson, Colin Cowdrey and debutant Alan Oakman back to the pavilion with just 17 on the board. What might have happened to England if Washbrook had not then survived a confident LBW appeal almost as soon as he got to the crease is anyone’s guess, as is what might have become of England if the Lord’s hero Miller had not been, courtesy of a sore knee, hors de combat as far as his bowling was concerned. As it was the Lancastrian’s historic partnership with his captain paved the way for England to total 325. When Washbrook was dismissed for 98 it was surely the only occasion in the history of the game when a Yorkshire crowd has been quite so disappointed at a Lancastrian failing to reach three figures. Australia’s batting was poor as they failed by 42 to make England bat again. Laker took 11-113 and Lock 7-81 as the pair bowled in tandem for the bulk of both innings.

And so to the momentous Old Trafford match. The Australians have always cried foul as far as the preparation of the wicket was concerned and, since the publication of Stephen Chalke’s splendid biography of the then Lancashire secretary Geoffrey Howard in 2001, we have known that they do, to say the least, have a point. But first a contemporary description from Bill Bowes, a man who knew a bit about bowling; In over 25 years, playing and watching at Old Trafford, I have never seen the playing strip so barren and such a reddy-brown in look. The absence of grass meant no help of any kind for fast bowlers. The colour meant that marl had been used in the preparation of the pitch, and spin bowlers generally agree they would rather see marl than anything else. When wet it will give the perfect “sticky” wicket. When dry it has a tendency to powder. Marl is no longer recommended for use in the preparation of pitches. It is a crumbly mixture of clays and carbonates and its use caused pitches to wear more quickly than they do now, thereby enabling spin bowlers to get bite, lift and turn as they wore. Of the 23 bowlers who took more than 100 wickets in 1956 as many as seventeen were spinners. Batsmen scoring second innings centuries were rare, and the number of unfinished three day matches was well down on the inter-war period.

There had been a Test at Old Trafford in 1955 for the third game of the South African series. Groundsman Bert Flack had produced a superb track with something for both batsman and bowler, and the game had produced more than 1300 runs with South Africa chasing down 145 with three wickets in hand with just minutes to spare. The plan was to do exactly the same again.

Two days before the match was due to begin Howard received a telephone call from Flack telling him the pitch was rather too dry and that he intended to water it. Shortly afterwards May rang Howard to discuss the pitch, and on being told of this advised Howard he would rather there was no watering. Forty years on Howard acknowledged that he should have told May, politely of course, to butt out, but being busy on other matters all he did was pass on May’s observation to Flack, who then did nothing.

So a pitch that should have been watered wasn’t. Next day there was a meeting on the square. Howard was there, as was Flack’s assistant, and Chairman of Selectors Allen. Flack’s assistant explained that the wicket would have a final cut in the morning. Allen looked hard at the ground and suggested that perhaps that shouldn’t be done. Howard stated that the message was duly taken back to Flack, and there was no cut.

How can Howard’s account, in so far as it relates to the non-cutting of the wicket, be reconciled with Bowes description of it as being “barren”? I am no groundsman but I suspect that the two are capable of being reconciled. The uncut strip would not have had much grass on it anyway, and a fear that Allen may have had was that another cut before play would have taken away what little there was to hold the pitch together, and meant that it would have been a dust bowl from the off. As it is there is a famous photograph of the groundstaff sweeping the pitch before Australia’s first innings and creating a such a dust storm in the process that the image might easily have been of a sub-continental wicket of the period.

However it may be that Howard was simply mistaken all those years later, as there is an alternative account, from Flack himself, which fits rather better with Bowes description. On that account Allen had, on the evening before the game, insisted that he would like a further cut despite Flack’s view that if that was done the pitch would do well to last three days let alone five. The cut was however duly administered, so perhaps the simpler reconciliation is that both accounts are true, but that Allen’s comments in Howard’s earshot on the Wednesday evening were simply his expressing himself to be unhappy with the cut happening the following morning, and that he went on to say, when Howard was not so attentive, he wanted it administered that evening (perhaps in the absence of any member of the Australian party or member of the press?). But this is not a case of the devil being in the detail, the point being that it is crystal clear that both England’s captain and Chairman of Selectors made their views known about how they wanted the pitch prepared and that, hardly surprisingly, Flack took note.

So for England it was vital for May to win the toss, as he had already done at Trent Bridge and Headingley. On that one the selectors, in producing the next rabbit from their collective hat, had sought divine intervention by calling up the Reverend David Sheppard to fill the problematic number three slot which, to date in the series, had produced just 45 runs in five innings. It is true that Sheppard had scored a fine 97 against the tourists for his county, but he had only played four First Class matches all summer, and in his previous eight Tests over six years had averaged barely 30. But May won the toss, and Sheppard went on to score 113, so as with Washbrook the selectors were right again.

Lindwall and Miller began with a traditional attacking field but, so easy-paced was the pitch, that after only three overs third man and fine leg were out. Benaud’s wrist spin and Johnson’s finger spin could make little impression either and England ended the day on 307-3 which, for the time, was exhilarating stuff. Next day proved trickier as Bailey, Washbrook and Oakman quickly fell, but Godfrey Evans scored a rapid 47 out of 61 and Sheppard and Lock added 41 as England totalled 459. After the groundstaff had whipped up their dust cloud Australia began their reply at 2.35pm.

Bailey and Statham opened the bowling against Colin McDonald and Burke. They were economical, each going for exactly one run per over, but the lifeless pitch meant they were no threat and after three overs from Bailey and six from Statham the two spinners were on. Even then Australia looked comfortable enough, albeit progress was pretty funereal. After 23 overs the score was 42 without loss, and it was then that May brought back Bailey for a single over in order to allow Laker and Lock to switch ends. At 48 McDonald pushed forward at Laker and an easy catch looped towards Lock at backward short leg. Four balls later Laker produced the delivery that he always said was the one that he treasured most in his entire career. It was to Harvey and although he had not, up until then, got very much turn from the wicket he produced what he himself described as an absolute snorter that pitched on leg and hit the top of off. Harvey was astonished and that single delivery had a huge psychological effect on the Australians.

With Harvey’s demise Ian Craig came into bat. He was barely 21 but had, as an 18 year old, toured in 1953. He and Burke saw Australia through to tea on 62-2. It was immediately after tea that the real drama unfolded the very first delivery after the interval catching Burke’s outside edge to give Cowdrey a comfortable catch at slip and Lock his only wicket of the match. Before the score had moved on Craig had been LBW to a delivery to which he should have played forward. That said four balls later, the score still 62, the left handed Mackay did play very firmly forward and found himself caught low down at second slip by Oakman, suggesting that in truth Laker was, by now, just about unplayable.

Miller struck one huge six from Lock to get off the mark but, despite suggesting to Laker’s leg trap that they were risking life and limb, he added no more to that before he pushed forward and popped up a catch to Oakman at square leg and it was 73-6. Despite Miller’s failure Benaud decided he too would try and hit his side out of trouble. In fairness to Benaud he did lay bat on ball but could not clear Staham at long on. 73-7. Ron Archer had watched those two dismissals from the non-striker’s end but he did not heed the lessons and at 78 he gave Laker the charge, missed the ball completely, and presented Evans with the simplest of stumpings. After that it was unreasonable to expect the last two men to do any better and both Johnson and wicketkeeper Len Maddocks were bowled playing back when they should have gone forward. It is worth remembering though that neither were complete rabbits by any means. Maddocks’ First Class career included six centuries and Johnson’s two.

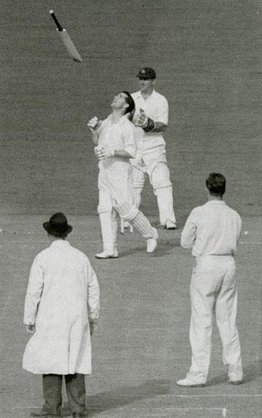

So Australia were 84 all out. A remarkable collapse after tea had seen eight wickets fall for 22. Laker had 9-37 the last seven of his victims coming in just 22 deliveries at a personal cost of only eight runs. May did not hesitate in asking Johnson to follow on 375 runs behind. Again Australia’s openers made a start, but their progress was interrupted when McDonald limped off with a knee injury in the eleventh over with the score on 28. Having been dismissed in the first innings from Laker’s best delivery of the match Harvey then completed a pair from the worst. It was a leg side full toss that he hit straight to mid on where Cowdrey accepted a straightforward chance. Harvey threw his bat in the air in frustration as he walked off. Craig then helped Burke take the Australians to 53-1 at the end of a remarkable second day.

On the Saturday there were only 45 minutes play possible, during the afternoon session, and Australia added just six runs and, importantly lost the wicket of Burke who failed to add to his overnight 33. It was a classic off-spinners dismissal via a catch by Lock at backward short leg. Craig was joined by McDonald and this pair kept the England spinners at bay, as indeed they did in the hour’s play that was possible on the Monday afternoon (Sunday was a rest day in those days) during which the score advanced to 84-2.

As the final day dawned the weather was still damp but in the end play began at 11.40, just ten minutes late. All the England bowlers tried to split up Craig and McDonald but the pitch had no pace for Bailey or Statham, and while Laker, Lock and Oakman (another off spinner although not in Laker’s class) all got some turn it was too slow to be of much help and Australia went into lunch on 112-2. Another two sessions and they had the draw. Sadly for them however over the interval a watery sun appeared that gradually got stronger and the pitch began to dry out – a classic sticky beckoned. Lock’s first delivery after the resumption spun sharply to slip – the writing was on the wall and no one was surprised when Craig’s dogged innings of 38 ended at 114 as he played back to a good length off break that spun sharply and caught him plumb LBW. Mackay came next and the left hander was greeted by three slips, a short mid-off, and two short legs as well as Evans breathing down his neck. His dismissal at 124 was a carbon copy of his first innings exit – at least Harvey wasn’t alone in recording a pair. Miller was next man in. In the first innings he had tried to clear the leg trap with some big shots. This time he went to the other extreme and refused to play anything with his bat unless he had to. After a stay of 17 minutes he was bowled, deciding at the last second to try and play a ball on a leg stump line he had initially shaped to kick away. He had not troubled the scorers. It was 130-5. Two deliveries later it was 6 – Archer too failed to score and was caught in the leg trap.

McDonald was now joined by Benaud and the Australians, not without Benaud antagonising the crowd with some blatant time-wasting, recovered their composure and got to tea without further loss. Again the interval did Australia no favours as two balls after the resumption McDonald’s fine innings ended when he too became a victim of the leg trap, more specifically Oakman at what was almost a leg slip. He had batted the best part of six hours for 89, much of it handicapped by his knee injury. He had not given a chance and no one who saw the match seriously suggested that his was anything other than the finest innings of the game. He and Benaud had put on 51. It was 181-7.

The game was up with Benaud’s dismissal at 198-8. While their future captain was still there, with his incessant gardening and taking a fresh guard every over, there was a chance England might run out of time. But for once Laker’s length forced him onto the back foot and the turn was sharp enough to beat the bat and bowl him. That was Laker’s 17th wicket, equalling Syd Barnes’ record. If he was nervous or conscious of making history he didn’t show it as he quickly removed Lindwall and Maddocks at 203 and 205 respectively. Lindwall was caught in the leg trap and Maddocks LBW to a delivery that forced him onto the back foot and turned. For Laker 10-53 for the innings and 19-90 for the match sat comfortably alongside a victory by an innings and 170. There were a few handshakes in the middle, but no histrionics. The Ashes had been retained, but Australia could still square the series at the Oval so the fifth Test, in the run up to which the Australians reeled off a series of convincing victories, was still important.

The England selectors went for another punt for the Oval choosing to recall a 38 year old Denis Compton for what proved to be his last home Test. In some ways Compton’s recall, given that he was not really fully fit after surgery to remove his kneecap, was even more surprising than Washbrook’s, but the result was the same. May won the toss, Australia made early inroads and in company with a recalled veteran May once again had to repair the damage. A further parallel was that Compton was, like Washbrook, eventually dismissed just short of a deserved century. The match itself was left drawn, the loss of more than 12 hours play preventing a result. At the end Australia were 27-5, once again at Laker’s mercy, and another hour would probably have been enough to see England repeat the 3-1 scoreline of 1954/55. It might also have seen Laker clock up a half century of wickets for the series. As it was he had to content himself with 46 at the remarkable cost of less than ten runs each.

Why did 19-90 happen and will it ever be repeated are the questions that are often asked and the answers surely are, to the first “luck”, and the second “no”. Laker was lucky for a variety of reasons not least that the man who finished top of the First Class averages in 1956, with 155 wickets at 12.46, managed just one wicket in 69 overs in helpful conditions against vulnerable opposition. There was no easing off by Lock as Laker neared the impossible. Lock always maintained, as was entirely in character, that he tried desperately hard throughout to take wickets and yielded nothing to his partner. In fact most of his teammates, when speaking later, thought he was perhaps trying just a little too hard. Whatever the explanation it must, given that Lock certainly didn’t bowl badly, have been down to luck that he took just the one wicket on such a helpful track.

Laker also got lucky with the way the pitch was prepared, and the fact that there was so little in it for the seamers. For two bowlers such as Statham and Bailey to not look like taking a wicket must, at least in part, be down to the vagaries of fortune. Laker was also looked upon kindly by the playing conditions, which suited his aggressive brand of off spin down to the ground. He was also fortunate to be able to use his leg trap in the way that he could. In 1956 he generally had, at least, a ring of three short legs, two men out in the deep at square leg and behind square, and a mid on. Occasionally he had as many as seven men on the leg side, but in any event usually three or four men behind the batsman. The law changed after 1956 to limit the number of leg side fielders to five, no more than two of whom could be behind square. Off spinners and inswingers could still have their leg traps, but they were never so intimidating again as in 1956.

So what of Jim Laker? With all that good fortune and his relatively ordinary pre 1956 form does he really deserve to revered in the way in which he is today? I have to say I think he does. He was a genuine slow bowler, a master of flight and change of pace who gave the ball as vicious a tweak as any finger spinner in history. A relative lack of success on his two tours of the Caribbean, and a failure to do a great deal against Bradman’s “Invincibles”, all in conditions that did not suit his bowling, unfairly skewed his figures. The real test of Laker’s class as a bowler came, in my view, in 1958/59 when, at the age of almost 37 he finally got to Australia, a trip he had missed out on in 1950/51 and 1954/55 on the basis that the selectors believed conditions would not suit his style of bowling. It was a very unhappy tour for England who played poorly and were beaten 4-0 by a keen young Australian side under Benaud’s tutelage. Laker himself was troubled by injury, particularly to his overworked spinning finger. He still managed to silence his critics though as, with 15 wickets at 21 runs apiece, he was England’s leading bowler, whether measured by average or by wickets taken.

After his return from Australia Laker had one more season with Surrey, but he was not as effective as in the past, and that coupled with the furore over a book of reminiscences, Over to me, meant he did not play for Surrey again. It was to the press box that Laker retired, and he became a respected writer and journalist and, as he passed 40, he turned out as an amateur occasionally for Essex for three seasons, enjoying considerable success. He went on to become, in partnership with Benaud amongst others, a respected BBC Television commentator whose laconic style, laced with a very dry humour, was loved by millions. Having listened to him for so many years I always found it easy to imagine the evening of Laker’s greatest triumph when, half way back to London at about 10pm, he stopped off at a pub near Lichfield for sustenance, and sat unrecognised in the bar as the rest of the customers were huddled around a small black and white television set watching grainy footage of the remarkable events that unfolded at Old Trafford earlier that day.

hey you probably don’t care, but I look on here quickly and write stuff in between working. I’m sure I want to read that, but I can’t commit the time required!

read it now, nice article

Comment by uvelocity | 12:00am BST 14 May 2012

Gun article – you and the staff writers seem to find the perfect topics to discuss.

I have long been fascinated by that bowling performance. And read a wonderful description of it as a youth by memory part of it was

[QUOTE]

And as Laker closed in on his final few victims – an extrordinary emotion beset the crowd. Unpatriotically they wished with all their will that the Aussies would survive the biting spin of Tony Lock and then it would be all on again – willing each delivery of Laker to be the one that would take the next wicket.”

[/QUOTE]

Comment by Hurricane | 12:00am BST 15 May 2012

Good article and very well written.

Comment by Himannv | 12:00am BST 16 May 2012