Bill Bowes – The Elland Express

Martin Chandler |

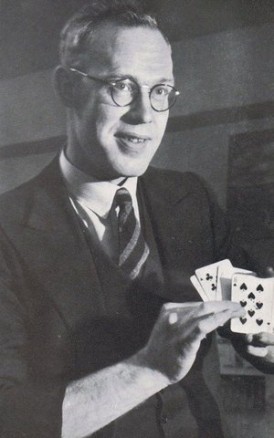

Bill Bowes was a caricaturists’ dream. He stood 6 feet and 4 inches in height, had blonde wavy hair and, in the days before contact lenses and laser vision correction he always wore glasses, even when on the cricket field. Add into the mix the fact that overall his bearing was rather more akin to that of a University Professor than a professional sportsman, and you had a man who, despite his involvement in the very serious business of bowling fast for Yorkshire and England, inspired much affection amongst those who knew him.

Born in the small Calderdale town of Elland in 1908 there was no great cricketing background in Bowes’ family, but his height meant that the schoolboy was much in demand amongst his games teachers. He was just 13 when he was recognised as being the leading cricketer at West Leeds High School. In those days Bowes was also a keen boxer, his incomparable reach allowing him to dominate his age group. Eventually however he came up against an opponent whose technique was good enough to expose the tall lad’s dodgy defence, and Bowes decided not to pursue the pugilist’s art.

At 16 Bowes left school and went into Estate Agency. Unlike some young sportsmen he was also a bright lad, and his parent’s had wanted him to go into teaching – it was just as well for Yorkshire and England cricket that Bowes was not keen, and that he knew his own mind. At this stage he did not play serious league cricket, and turned out for the Armley Park Wesleyans in friendly matches. It rapidly became clear however that he was punching well below his weight as he proceeded to take 80 wickets at just three runs each over the course of his first season, and he moved on for the next summer to play for Kirkstall Educational. His time in their second XI lasted exactly one week, six wickets for five runs incuding a hat-trick seeing his immediate promotion to the first team, who played in the Yorkshire Council, a much higher standard than he was used to. Not that that held him back, although he wasn’t his side’s most successful bowler on debut at Hanging Heaton. That honour went to his opening partner who took 5-8, but Bowes 5-9 helped dismiss the home side for just 18.

By this time the 18 year old trainee Estate Agent was understandably thinking in terms of a career in the game, as were Kirkstall Educational, a member of whose Committee effected an introduction to Warwickshire. Unfortunately for the West Midlands county Bowes himself had been doing his homework and learned that the MCC were looking to recruit young professional cricketers and he wrote to the club, was successful in his application, and set off for London.

By then 19 Bowes made his First Class debut for MCC in 1928. On only his second appearance, against Cambridge University, he did the hat-trick and that performance brought him to Yorkshire’s attention. The county did not have a bowler of genuine pace and were extremely interested in Bowes. The only problem was that he had signed a nine year contract with the Marylebone club. Discussions took place and MCC, with no desire to impede the progress of a promising young cricketer, were happy to allow Bowes to play for Yorkshire provided they had first call on his services for their own First Class fixtures. One result of this was that it was 1939 before, in the traditional curtain-raiser to the new season at Lord’s between Yorkshire and the MCC, Bowes played for his county rather than their opponents.

In truth Yorkshire had every reason to be grateful to the MCC, as the coaching Bowes received there from the former Lancashire paceman Walter Brearley was vitally important to his developing into the top-class performer that he became. It was Brearley that urged him to adopt the short ten pace run up that allowed him to maintain his accuracy for long spells, and to take full advantage of the natural inswing that his action produced. Brearley also stressed to Bowes the importance of his cultivating an outswinger to complement his stock delivery. It was to be 1931, and a piece of advice about the positioning of his feet that the studious Bowes found in an obscure coaching manual that finally enabled him to bowl the outswinger more or less at will and without any perceptible change of action, but it was Brearley’s advice that set him on his search for the delivery and with his help he did manage to bowl it occasionally as he demonstrated when playing against Yorkshire for the MCC in the 1929 season at the Scarborough Festival in September. Yorkshire had persuaded the by then 58 year old George Hirst to come out of retirement for the match and he became one of Bowes seven victims, the top of his off stump being clipped by a delivery that started off going towards the leg side. As the old campaigner walked past Bowes on his way back to the pavilion he said to him Well bowled lad, that one would have been too good for me when I could play.

In 1930 Bowes just reached his hundred wickets for the season and paid 19 runs each for them. That outswinger perfected he took 136 the following summer, at a cost of just 15. He cut his average slightly again in 1932 and, with 190 wickets, pushed himself right to the forefront of the domestic game. The Indians were in England ninety years ago and played an inaugural Test against the full strength of England. For the first time Douglas Jardine was England captain and the opening bowlers selected were Bowes and Bill Voce. With six wickets for the match Bowes was the most successful member of England’s attack although he did upset his captain, and thereby learnt a valuable lesson about him. In India’s second innings Jardine asked Bowes and Voce to bowl at least one full toss per over, his reasoning being that the absence of a sightscreen at the Pavilion End would make batting much more difficult. Neither bowler obeyed and, England winning comfortably enough, Jardine was not unduly concerned, but the meticulous attention to detail that characterised his captaincy had been demonstrated, and he explained afterwards to both bowlers that in future they would follow his instructions, whatever their own opinions might be.

The quicker bowlers named for the trip to Australia that winter were Voce, Harold Larwood, Gubby Allen and Maurice Tate and, in the fashion of the day, they had been named in dribs and drabs through the course of the season. So by the time Yorkshire and Bowes rocked up at the Oval for a Championship fixture in late August Bowes would have known that he was wintering at home. He was fast medium rather than genuinely fast although he was always willing to use the bouncer, albeit he generally did so sparingly. His height was such that he was usually better off relying on the extra lift he could get from deliveries on a good length. As Plum Warner commented during his trial for the MCC groundstaff his talent for .. grinding the batsman’s fingers against the bat handle. was one of his great strengths. But to return to the Surrey match the 49 year old Jack Hobbs was at his best on the first day as he scored 90. No one else in the match (won by Yorkshire by three wickets) scored more than 37 and of the other Surrey batsmen only Jardine, with long vigils for 35 and 29, made more than 21. Eventually, and not unreasonably, Bowes dug one in at “The Master” who signalled his disapproval by walking down the pitch and pointedly tapping at a spot in the bowler’s half of the pitch. Bowes was essentially a genial man but this angered him and, much to Hobbs’ discomfiture, he then got several around his ears in rapid succession. All the time the batsman at the non-striker’s end, Jardine, was taking note. Despite the surfeit of pace bowling he already had (the name of Walter Hammond should be added to the list already given) the Iron Duke got his way and just three days before the party set off for Australia Bowes was called up.

After the “full tosses” incident at Lord’s it is perhaps no surprise that in the early part of the Bodyline tour Jardine and Bowes clashed. In one of the early fixtures Bowes asked Jardine for another man to strengthen his leg side field. Jardine refused telling Bowes he would not give him one extra leg side fielder, but that he could have another four. Bowes was angry with Jardine, and that in turn made Jardine angry with Bowes. Fortunately for both that evening Jardine took the trouble to explain his tactics and, that misunderstanding cleared up, a great mutual respect began that, in later years, developed into a solid friendship.

For Bowes there was just one appearance in the Bodyline series, in the second Test, the one that England lost, when he replaced Verity in an unsuccessful gamble on a four pronged pace attack. He only took one wicket in the match, although it was an important one, and a story that he never tired of telling. Bradman had missed the first Test, won comfortably by England, and all Australia expected him to win the second Test for them. He did in the end, but not in the first innings when he came to the wicket at 67-2. He received a momentous ovation from the crowd at the MCG so much so that the cacophony prevented an immediate resumption of play. Bowes, just for something to do, started making minute adjustments to his leg side field. Bradman, doubtless for the same reason, watched intently. Bowes, reasoning that Bradman now expected a bouncer, duly decided to bowl short of a length on a leg stump line, but not to dig the ball in. His plan worked to perfection as Bradman played for lift that wasn’t there and dragged the ball on to his stumps. Bowes would always add at the end of the story a vivid description of the delight that his captain showed at the dismissal.

Overall Bill Bowes career figures are simply magnificent. In all First Class cricket he took 1639 wickets at at a cost of just 16.76. The only pace bowler of note who has a better record, and then only just, is Brian Statham, and it is worth bearing in mind that for well over a third of his career Bowes had to contend with the old lbw law, which prevented his inswinging deliveries that pitched outside off stump getting him any decisions at all. Yet despite that he played in just 15 Test matches. Was he less successful at the highest level? Certainly not – in those Tests he took 68 wickets at only 22, so fine figures. If more confirmation is required of those 15 matches just six were against Australia. Despite that limited exposure to the great man Bowes removed Bradman five times in all, and each time by his own efforts – four were bowled and the other caught at the wicket. He only dismissed Bradman cheaply the once, but that does not significantly lessen the achievement. One of the six matches against Australia was the Oval Test in 1938 when Hutton scored his 364 and, as a result of the ankle injury sustained while bowling, Bradman did not bat at all, so in truth it was five in five. Curiously, or perhaps even perversely, in six other matches in which the two opposed each other Bowes did not dismiss Bradman on even a single occasion.

So purely in terms of their bowling every man who played for England in the 32 Test matches between Bowes’ debut and the outbreak of war was statistically his inferior. Why then, given that he was seldom injured, was he overlooked so often? The main reason must lie with his batting and fielding. As far as Yorkshire were concerned Bowes had just one job, to be the spearhead of their bowling. He had no pretensions as a batsman and was never encouraged to harbour any. Similarly in the field he was invariably placed at mid on. He was expected to try and catch anything that came within reach, but he was not supposed to chase the ball – the last thing Yorkshire wanted him to do was to waste energy that could be used for bowling by fielding or batting. Given Bowes’ fitness record, coupled with the fact that in seven out of the ten seasons in the 1930s Yorkshire were champions, it is difficult to fault the county’s reasoning. Overall Bowes scored more than 100 fewer First Class runs than he took wickets.

Only once before the war, in 1937 when he missed a number of games after knee surgery, did Bowes miss out on getting his 100 wickets, and he always paid less than 20 runs each for them. Even in his two post war seasons, by which time he was nearly forty and still affected by three years spent in captivity following his capture at Tobruk in 1942 ( his time in various camps had resulted in the loss of four and a half stone in weight) his reduced haul of wickets still cost the usual 16 runs each. His consistency was remarkable as, in the circumstances, was his longevity.

The duration of Bowes career, and his lack of long and frequent absences through injury, was doubtless a result of his economical action, described light-heartedly by Neville Cardus as a somnambulistic gait bowled as though sleep was still drowsily soothing his limbs. In similar vein, albeit rather more fully, “Crusoe” Robertson-Glasgow echoed the point when he wrote Bill’s run up when bowling is a leisurely business. I sometimes wonder whether he is going to get there at all. His whole approach to the supreme task in cricket suggests, quite falsely, indolence, negligence, almost reluctance. But he is just keeping it all in for the right moment. If you watch closely you will see the full use of great height, strong shoulder and pliant wrist. His direction is unusually accurate; he varies his pace to suit the pitch; he can swing even a worn ball very late from leg, and often with an awkward kick.

As a man Bill Bowes was charming, intelligent and generous. In his playing days he qualified as a football referee, a skill that proved useful down the years in assisting teammates and others with benefit functions. He also, purely because it interested him and for no other reason, became an accomplished magician, another skill which was put to use mainly for the benefit of others. After he left the game he coached Yorkshire for many years and, after publishing an excellent autobiography, Express Deliveries, without assistance in 1949, he also became a full time journalist. He did not play much cricket after retirement but, as one story amply demonstrates, he remained a formidable bowler. The setting for the tale is the Yorkshire nets with Bowes at the bowler’s end looking after his protege and Arthur “Ticker” Mitchell at the other end looking after his. Bowes tired of watching the young batsman gaining the upper hand and demonstrated a point to his pupil by bowling himself. The young batsman lost a stump. Bowes continued, without Mitchell remaking the wicket, and he took out another stump, Well thee might as well finish t’job was Mitchell’s weary shout and, of course, Ticker’s young batsmen learned the same lesson as Bowes’ young bowler as the last stump was removed by the third delivery.

When he reached retirement age, in 1973, Bowes left his full time job with the Yorkshire Evening Post, although he continued to write about the game for the rest of his days. It is a great shame, given the quality of his autobiography and the only other book he wrote, an account of the 1961 Ashes series, that his work has never been showcased in an anthology and any publisher who wants an idea for a cricket book that would sell steadily could, in my view, do a lot worse than fill that particular gap in the game’s literature. Bill Bowes was in his 80th year when he suffered a fatal heart attack at his home near Otley in September 1987, twenty or so miles from where he had been born. Unsurprisingly there were a steady flow of tributes from family, friends and former teammates and colleagues. He would have particularly liked Len Hutton’s description of his bowling style as ..a little bit of Bob Willis, and a lot of Richard Hadlee.

Great article and exceptionally well researched. So much info in there that gives a lot of insight into who he was. Fantastic job.

Comment by Himannv | 12:00am GMT 11 February 2012

Very rare info. Nice article.

Comment by Emily | 12:00am GMT 11 February 2012

A very worthy subject for a fertang bio (:cool:) and the author doesn’t disappoint.

I may be confusing my cricketers, but I vaguely recall a story about Bowes’s treasured journal being lost on a long train journey? A terrible waste if so.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 11 February 2012

Enjoyed reading that, great piece.

Comment by silentstriker | 12:00am GMT 11 February 2012

Nice article, I enjoy reading a bit of history. Its a good research performed!

Comment by Mcaray | 12:00am GMT 11 February 2012

I wonder what the little bit of Bob Willis Hutton saw in Bowes? They were about the same height but you’d assume he would be comparing bowling methods. The likeness to Hadlee though appears accurate after reading about Bowes’ bowling methods such as his pace off the pitch, accuracy, the surprise use of the bumper (this an evolutionary change in his bowling methods) and command of swing both ways.

Comment by the big bambino | 12:00am GMT 22 January 2013

It’s great to have come across this excellent article on Bill Bowes. One thing missing is that Bill also took some fantastic film of the Ashes series in Australia in 1950/51, ’54/5 and ’58/9. These were deposited with the Yorkshire Film Archive by his son, and one of them can be seen online at the YFA website from June 2013.

Comment by Steve Morley | 12:00am BST 22 May 2013

As Charlie Sheen says, this article is “WNNGINI”

Comment by Vivek | 12:00am BST 10 September 2013