Improving the Invincibles

Martin Chandler |

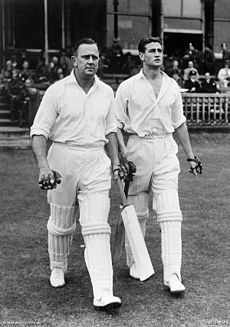

Don Bradman’s 1948 Australians weren’t known as “The Invincibles” without good reason. Occasionally the weather intervened and an inexorable victory march was thwarted, but only once, at Bradford early in the tour when Yorkshire gave the tourists a fright before succumbing by four wickets, was there any evidence of human frailty. That relatively narrow victory over the White Rose and the odd rain-affected draw apart the results were generally innings victories interspersed by the occasional win by a large number of runs or wickets.

Against that background it is remarkable to think that the Australian side might have been stronger still but, particularly in its spin bowling department, it may well have been. Four particular individuals would surely, in any other era, have had long and successful Test careers. As it was Cec Pepper and Bill Alley never played so much as a single Test, and George Tribe and Bruce Dooland played just three each. Australia’s loss was, in the case of all four, English league cricket’s gain, and in respect of Dooland, Tribe, and latterly Alley, that of the County Championship as well.

Why didn’t they make it? In Alley’s case the main reason was doubtless his age and a lack, through no fault of his own, of recent form when the Invincibles were selected. As for Pepper his caustic and combative personality ruled him out. For Dooland and Tribe it was more a case of just missing out. They were both wrist spinners, and two of their kind were selected, Doug Ring and Colin McCool. All four had had opportunities at home against England in 1946/47 and India the following season and if the sole criteria for selection were what had been made of those chances then the selectors got it right. It is only with the benefit of hindsight that the claims of Dooland and Tribe appear difficult to resist.

Cec Pepper, oldest of the quartet, was also the one seen least in First Class cricket. He was a big man, never much under 16 stone in weight, and was primarily a leg spinner with a full repertoire of variations. He made his First Class debut before the war and in the last two seasons before the game was suspended took 57 wickets at just over 30 as well as scoring useful runs. Immediately after the war he was an integral part of the Australian Services XI which toured England and played a series of five “Victory Tests” in 1945. His one First Class century, a very rapid 168, came at the end of the tour in a festival game at Scarborough and the ferocity of Pepper’s hitting that day was talked about by those who witnessed it, and many who didn’t, for the rest of their lives.

When the Services XI left England they were still not done and played matches through India and Ceylon before finishing the tour with six matches against the Australian states. The events of the game against South Australia were the key to Pepper never playing for his country. Bradman scored 112 for the home side and Pepper was convinced that he had dismissed him twice only to be denied both times by the umpire. Pepper lost patience and, using the sort of robust language that he was famous for, queried with the umpire the issue of whether it was in fact possible to get a decision gainst Bradman on his home ground. At Bradman’s request the umpire complained to the Board of Control. An apology was demanded of Pepper and duly written. The apology, which teammate Dick Whitington had helped to draft, was acceptable to the umpire but was apparently then lost in transit and did not reach the Board. A further letter was demanded but by this time Pepper had already been left out of the side that was to visit New Zealand, and he had decided his future lay in England, so he saw no point in pandering to the Board’s wishes.

Keith Miller, a teammate in the Services XI, writing in 1957 said that at the time Pepper was, in my opinion, the best all-rounder in the world. He went on to describe the report made of the incident, which he had seen, as finishing Pepper’s Australian career, and he was critical of Bradman for not intervening to rescue the situation.

Interestingly a few years before Miller’s words were written, in 1950, Bradman wrote of Pepper that he ..showed every sign of being a great player and that he made the ball turn from the off by some unique method of delivery which even now remains a mystery to me. The delivery that caused all the trouble back in 1945 was a flipper that totally deceived the great man and caught him, in the eyes of Pepper and all his teammates, but not the umpire, plumb in front of the stumps.

Pepper’s only other run of First Class matches came when he visited the sub-continent with a strong Commonwealth XI, including Alley and Tribe, in 1949/50. He took 34 wickets at less than 16 but despite that it was agreed he should return home early, the local umpiring being so poor that Pepper’s reaction to it was coming into conflict with the general spirit of goodwill and bonhomie that was accompanying the tourists.

Australia’s loss was the Lancahire League’s gain. Pepper broke plenty of records, and earned a great deal of money before, in 1964 at 48, the old poacher turned gamekeeper and joined the First Class Umpires list in England. Nothing much changed though, and Pepper always called it as he saw it. He was obedient enough to toe the line when he was told by Lord’s not to no ball Charlie Griffith for throwing, but not sufficiently subservient to ensure that his exchange of correspondence with his employers on the subject did not find its way into the national press. He also failed to adhere to the usual practice of many umpires to “favour” the county captains (upon whose reports their livelihoods depended) and when he then questioned the procedure for the selection of the Test panel, and received a response he didn’t like, he resigned. That was in 1979 and he left the game then to concentrate on a packaging business that he had started in Rochdale some years previously. He died, aged 76, in 1993.

As to stories about Pepper they could fill a book in themselves, so I shall restrict myself to just three. One of the best known concerns an exchange with a league umpire who, so sayeth one version of the story, was a priest. After a particularly frustrating afternoon at the umpire’s hands legend has it that Pepper had decided to apologise for his over-zealous, loudly exclamatory appealing coloured with sundry expletives and did so. The umpire reassured Pepper that he didn’t mind and that it were all part o’t’game, and then retorted after the next appeal, Not out, you fat Australian bastard!

There were accusations of racism levelled at Pepper from time to time, although as he was certainly a great friend of both Frank Worrell and Garry Sobers that seems misplaced. He was certainly however less than politically correct, his usual greeting to Asian batsmen being Have you brought your prayer mat with you? Because you’re going to ******* need it and on one occasion shouting at opposing professional Gul Mahomed, who was unable to lay bat on ball that As a batsman you’d make a ******* good snake charmer

And finally, Pepper’s views on a certain English all-rounder, expletives deleted; Botham? The world’s best all-rounder? Hell, he wouldn’t have got into the New South Wales dressing-room in my day. I could have bowled him out with a cabbage, with the outside leaves on. And as a bowler, well, he wouldn’t have been good enough for Bradman.

In many ways Bill Alley was a kindred spirit of Cec Pepper although, by dint of the fact that he did get to umpire in Test matches, he must have exercised just a little more restraint somewhere along the line. He was born in Sydney in 1919 although there were some who, on account of the early age at which he must therefore have started playing Grade cricket, believed him to be a couple of years older. Well after his playing days ended Alley was still protesting that his birth certificate was misplaced but, for my purposes, I shall assume the date in Wisden, 3 February 1919, is the correct one.

The young Alley had many occupations amongst them a blacksmith’s striker, boilermaker’s assistant, oyster fisherman, deep sea fisherman, car greaser, cider brewer, chicken farmer and dancehall bouncer. In 1945/46 he made a marvellous start to his First Class career as he scored three centuries for New South Wales in averaging almost 70. He hoped for further success in the following year but his season ended early after a sickening accident in the nets. A delivery in a neighbouring net was hooked ferociously towards him where, finding a weak part of the net, it passed through and struck him on the jaw. He spent more than 48 hours in a coma and needed 60 stitches. A promising boxing career, as a welterweight he had won 28 bouts out of 28, ended with the injury.

If that were not bad enough things got worse the following season as in quick succession Alley’s wife died in childbirth, and all in the same six month period his mother and mother-in-law passed away as well. It is hardly surprising in the circumstances that he decided that a complete change was the way ahead for him and, the difficult decision having been taken to leave his two year old son in the care of family members, he turned up in Lancashire in April 1948 for the first of five successful seasons there with Colne in the Lancashire League. At the end of those five years he moved on to ambitious Ribblesdale League side Blackpool. The seaside club was wealthy, but the league somewhat inferior to the Lancashire League in terms of playing standards, and Alley made hay with bat and ball, averaging more than 100 with the bat during his four seasons at the club.

Throughout his nine years as a club professional Alley received regular approaches from the counties but they couldn’t afford him. There was much more money available in the leagues, for rather less work. At a time when county cricketers had to find winter employment in each close season Alley had no such concerns. He did work in three close seasons, but only because he chose to. The downside of the club professional’s life was a lack of security. The clubs seldom gave contracts for longer than a year and while Blackpool wanted the by now 38 year old Alley back for 1957 they refused to offer anything beyond that season. Somerset on the other hand were prepared to offer a three year deal, with a testimonial at the end of it so, despite the pay cut, Alley decided to have another go at the First Class game.

It helped that Somerset were prepared to allow him to open the batting, and his powerful cuts and pulls brought him his 1,000 runs comfortably in each of the three years. His accurate medium paced swing bowling also brought him his share of wickets each season and Somerset were sufficiently please to re-employ him. Alley’s tally of runs was just 800 in 1960, but anyone who thought the 42 year old was on his way out by 1961 were forced to eat their words as he became, and will doubtless remain in perpetuity, the last man to score more than 3,000 First Class runs in an English season. The following year, having backed himself to do so to the tune of GBP50 at 10-1, he managed the double, and was very close to 2,000 runs. He never touched those heights again of course, but as late as 1968 a 49 year old Alley got his 1,000 runs and chipped in with 36 wickets. He was offered another contract, but just to play the limited overs game. Alley did not fancy that so he rejected the offer and, to maintain his day to day contact with the county game, he joined Pepper as a First Class umpire. He remained on the list for 15 years and stood in ten Tests, most notably at Old Trafford in 1976 when, many would say belatedly, he instructed Clive Lloyd and Michael Holding that the short-pitched assault on Brian Close and John Edrich had gone on too long.

After moving to Somerset Alley never left and he was 85 when he died in 2004. He was survived by his second wife and their two sons. One of the happiest days of Alley’s life had come in 1951 when he visited Australia to collect his eldest son who he had not seen since 1948. Ken was the best cricketer amongst the three boys, and had trials with Somerset, but tragedy had not stopped stalking Bill Alley and in 1970 Ken, by then a serving soldier, was killed when a tank he was in overturned in a freak accident.

There are as many stories about Alley as there about Pepper, and as the years pass these two great Australian characters have become interchangeable in many of them, but I am confident that both of those I intend to attribute to Alley are indeed his.

One of the more notable features of Alley’s career, like Tribe’s, was the success he enjoyed against the best and during his career span that meant Yorkshire. Of the sixteen First Class counties that Somerset encountered he did better with the bat only against Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. Somerset batsmen were generally beaten by the Yorkshire bowlers before they started, and there are several scorecards over the years of Alley’s career that will have caused acute distress to West Country eyes. An example is Alley’s first ever encounter with the White Rose in May 1957 at Headingley. The result, unsurprisingly, was an innings victory for the home side. Alley top scored in both Somerset innings with 47 out of 144 and 39 out of 104. Legend has it that throughout his innings he was deeply critical of the bowling of Fred Trueman. In fact so caustic were his comments that Trueman, long known as having more to say to batsmen than anyone else on the county circuit, was for once all but struck dumb by this unfamiliar Australian, and he found little to say in response. The story goes that after the first day’s entertainment was concluded, as the Somerset side wandered into the bar, Fiery Fred announced to a teammate that he wanted to go and buy Bill Alley a pint. As he got up to leave he looked his teammate in the eye, and in all seriousness said as an aside Mind you t’booger dun’t ‘arf swear a lot.

My other Alley story, that I heard at a sporting dinner, involves umpires. All expletives are deleted from this as, on the basis of the way I originally heard it, the “8” and “shift” keys on my keyboard would be worn out otherwise. Alley wasn’t getting much change out of one of the grumpier umpires on the circuit and as he went up for a catch at the wicket screamed at the umpire in relieved tones ..even you must have seen that one – how was he? The umpires reply was Not Out – and what did you say? Alley’s reply was, perhaps predictably, so you’re deaf as well as blind then!

My third man, George Tribe, was born in 1920 but did not make his First Class debut until after the war. When he did his entry was spectacular, as in his first two seasons he took 88 wickets at just 22 runs each, a remarkable record for a bowler who was that rarest of beasts, the left arm wrist spinner. He was also a useful batsman, averaging 20 and contributing three half centuries to Victoria’s cause. It came as no surprise when he forced his way into the Australian side for the first Test against England in 1946/47. Keith Miller and Ernie Toshack were largely responsible for blowing England away in a game that Australia won by the small matter of an innings and 332 but Tribe got a couple of second innings wickets and retained his place. He did not bowl badly in the second Test, but in terms of wickets taken he was outbowled by the off spin of Ian Johnson and Colin McCool’s leg breaks. He came back into the side for the fifth Test but again he had no luck, whereas McCool took six wickets, and those two scalps at the ‘Gabba proved to be the only two he ever claimed at Test level.

After 1946/47 Tribe never played another First Class match in Australia. By May 1947 he was Milnrow’s professional in the Central Lancashire League. He set a record for the League with 148 wickets in 1948 and he increased that to 150 the following year, before moving on to the Lancashire League. On the Commonwealth XI tour in 1949/50 he took more than twice as many wickets as anyone else, although without Cec Pepper’s early return he would have had rather more competition.

In 1950 Tribe, who was an engineer by profession, obtained employment with British Timken. In those days that company effectively owned Northamptonshire and it was no surprise that he signed a contract with the county for the summer of 1952. In his eight seasons with Northants he completed the double in all but one of them and was a major factor in the transformation of a county that was consistently in the bottom two in the 1930s, to one that was 4th, 2nd and 4th again between 1957 and 1959. Like Bill Alley Tribe saved his best performances for Yorkshire. He took 78 wickets in all against the White Rose at just 15 runs each, his best figures against any of the counties.

At the end of the 1959 season, although Northants offered him another contract, Tribe decided that he had had enough of the county circuit and he returned to Australia where he worked for Timken’s Australian outlet. He lived to be 89 and when he died in 2009 he was the second oldest Australian Test cricketer. Unlike Cec Pepper and Bill Alley he was a genial and mild-mannered individual, but that much conceded he was no less competitive than his more exuberant countrymen.

The youngest of the quartet was Dooland. Like Tribe he lacked the abrasiveness of a Pepper or an Alley but his record clearly demonstrates that he was at least their equal as a cricketer.

Despite being primarily a leg spinner Dooland was just 17 when he first received an invitation to play for South Australia in the Sheffield Shield in 1940. Sadly for him the bank he worked for would not permit the time off so he had to wait unto after the war to make his debut. Having done so he did enough to earn a place on the trip to New Zealand in January 1946. He also played twice against England in 1946/47. He took eight wickets, all front line batsmen, but having replace Tribe for the third and fourth Tests he had to give way to him in the fifth. His one opportunity against India in 1947/48 brought him just 1-68 and he was overlooked for the 1948 tour.

The following domestic season was rather less successful for Dooland and he signed a contract to play for East Lancashire in the Lancashire League for 1949 and he stayed with the club for the next four seasons. In the first year he comfortably did the double, a rare feat, and was persuaded to sign a three year contract. His record in those three years did not touch the heights of 1949 but he was still a highly effective performer and he also did extremely well on a Commonwealth XI tour of the sub-continent in 1950/51. He received an offer from Nottinghamshire and it was there, where he spent five seasons, that he really made his name. In total Dooland took 770 wickets for the county at less than 19 runs each and he scored sufficient runs to do the double twice, and end up just 30 runs short on a third occasion. He amply demonstrated that wrist spinners could succeed in England. In 1954 he was all but unplayable at Trent Bridge as he had 10 wicket match hauls in ten of his thirteen appearances there. He was a little quicker than most, but had a full repertoire of deliveries at his disposal and he was, in 1956, the man who showed Richie Benaud how to bowl the flipper.

Dooland’s batting was steady rather than spectacular, and he was also very consistent. There was just one century for Notts, but as many as 33 fifties. His last season, 1957, was by far his best with the bat as he scored more than 1,600 runs to go with his 141 wickets, but he chose not to stay and returned to Australia, his reasoning being that he wanted his children brought up as Australians. He played for South Australia in the 1957/58 season but that was it and, at just 34, Bruce Dooland was lost to the First Class game. He died suddenly in 1980. He was just 56.

Although I have highlighted just four individuals there were other Australians who, had they not thrown in their lot with league and county clubs in England just after the war would, it seems to me, almost certainly have played Test cricket for their country at some point in the 1950s. Some more examples include pace bowling all rounder Fred Freer, who did better than the man he shared the new ball with, Keith Miller, in the one Test match he played in 1946/47. He spent three years with Rishton before being blacklisted for breaching his contract (a “distinction” he shared with Miller, Indian Test player Lala Amarnath and, briefly, Sid Barnes). Ken Grieves, mainly a batsman but also a useful change bowler arrived in Lancashire in 1947, initially filling the void created by Miller’s change of mind. He stayed to play for Lancashire for more than a decade. Another batsman was Jock Livingston, the man who had the misfortune to have struck the ball that shattered Bill Alley’s jaw, who was a consistent run scorer for Northamptonshire through the early 1950s. There were others as well although none apart from my featured four who would, even with more than sixty years hindsight, have enhanced the 1948 tourists.

As a matter of linguistics one cannot, by definition, make someone or something that is invincible more invincible, but I rather think that if Cec Pepper, Bill Alley, George Tribe and Bruce Dooland had been given the places eventually occupied by Colin McCool, Ron Hamence, Ian Johnson and Doug Ring, that “The Invincibles” would have been an even stronger combination than they eventually were. I won’t shout that too loudly though, as there are still a few men left alive who felt the full force of Bradman’s team, and at their venerable age I doubt it would do too much for the health of the likes of John Dewes, Hubert Doggart, Doug Insole, Tony Pawson and Clive van Ryneveld to have to imagine an even stronger set of Australians to that which administered humbling defeats to the various sides they represented in 1948.

Insole’s Essex lost by an innings and 451, Dewes played for Cambridge University, England and Middlesex and lost by an innings twice and ten wickets once. For Doggart he was in the same Cambridge side as Dewes, as indeed was Insole, but unlike Insole Doggart managed to miss the defeat of his county, Sussex, by an innings and 325. Pawson and Van Ryneveld played for the Oxford University side that lost by an innings. Pawson’s Kent also had a humbling defeat, although an innings and 186 was rather better than Sussex and Essex managed. I am sure all of them are satisfied that The Invincibles were quite strong enough without some young whippersnapper trying to conjure up an argument as to why they were fortunate that the Australian selectors “went easy” on them!

Interesting article but not convinced they would have added that much. Selectors knew what they were doing, imo.

Comment by Debris | 12:00am GMT 6 February 2012

Gun article.

Comment by GingerFurball | 12:00am GMT 6 February 2012

Very interesting piece Martin. Interestingly Alec Bedser thought Dooland good enough to include him in his best-ever Test XI.

Comment by Dave Wilson | 12:00am GMT 6 February 2012

Well McCool had the numbers in tests and was also successful in county cricket. Tribe bowled too many 4 balls in 1946 (Cary). Doolan was also unsuccessful. Of course if they had battled it out they may have got the spots that went to Ring, Hill, early Benaud and even Iverson in late 40’s and early 50’s. But Aust selectors were always pretty harsh on guys who didn’t front up each year for shield cricket. Joe DB

Comment by Joe Drake-Brockman | 12:00am GMT 9 February 2012

Brillian article it was like hearing Cec himself. A very accurate account of his life and fantasic personality.

Regards

Gill

Rochdale UK

Comment by Gillian Peel | 12:00am GMT 24 March 2012