Son of a Preacher Man

Martin Chandler |

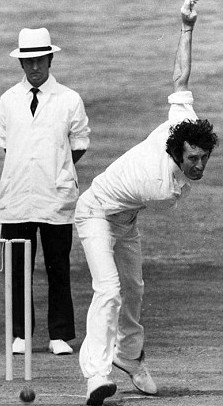

Pace bowlers have always been one of cricket’s big attractions. There is nothing like the prospect of seeing a great fast bowler to bring crowds flocking to a cricket ground. Put a pair of top performers together and you give them cricketing immortality. From Gregory and McDonald in the 1920s the line runs through Larwood and Voce, Lindwall and Miller, Heine and Adcock, Statham and Trueman, Hall and Griffith, Lillee and Thomson to Wasim and Waqar.

There are some heroes from the past who are not, it seems to me through lack of a fellow headliner, remembered with the reverence that they should be. The Australian Garth McKenzie is one, but the most striking example in my view is the Englishman whose career partly overlapped with McKenzie’s, John Snow.

Snow’s background did not suggest that he would be following in the footsteps of Harold Larwood and Frank Tyson by terrorising Australian batsmen in an Ashes series. His father was a Scottish vicar, and his middle name came from a fourth century Christian Philosopher, St Augustine. Outside cricket Snow wrote poetry, and indeed published two slim volumes of his work both of which demonstrate a sensitivity and a gift for self-expression somewhat at odds with the fiery and often boorish persona that he showed on the field of play.

After making one appearance in 1961, and two in 1962 a 21 year old Snow forced his way into the Sussex side in the second half of the 1963 season. He was nursed through, averaging barely twenty overs each game, but his 29 wickets cost a respectable 24 runs each.

1963 was the year of the first English one day final. Snow’s Sussex, captained by the forward-thinking Ted Dexter, quickly got to grips with the tactics and got to the final. Snow hadn’t played in the early rounds but was picked for the final that was played before a full house at Lord’s and a nationwide television audience. It was a grey day in St John’s Wood and the light was fading on Worcestershire’s unsuccessful run chase when those watching had their first look at Sussex’s fifth bowler. Snow was far too quick for the West Midland county’s batsmen. His eight overs cost just 13 runs and he took three wickets. Sussex were back the following year and won again, this time brushing aside the other side from the West Midlands, Warwickshire. On this occasion Snow was first change and, with 2-28 from 12 overs, impressed once again.

In 1965 the England selectors called on Snow for the first time. This was the season when, for the first time since the disappointing 1912 Triangular Tournament, there were twin tours. The first half of the summer saw a pretty weak New Zealand side visit. Later on a much stronger South African combination arrived. Through the course of the summer the selectors demonstrated the sort of indecisiveness that has almost always led to disappointment. For the first Test against New Zealand, won comfortably by England, the seam attack consisted of the veteran Fred Trueman, the Somerset left armer Fred Rumsey and medium pacer Tom Cartwright.

Cartwright was omitted for the second Test and Snow took his place. It was to be Trueman’s final Test. The young tyro’s selection, perhaps helpfully, was overshadowed by the dropping of Kenny Barrington who had scored a century in the first Test, but too slowly for the selectors’ liking. Snow contributed four wickets to another comfortable victory, but then picked up an injury. For the third Test the Northants giant Dave Larter came in to share the new ball with Rumsey. They were the only seamers selected. England won easily once again.

For the first South African Test Snow was still unfit so another debutant, David Brown of Warwickshire, led the attack with Rumsey and Larter. England were fortunate to avoid defeat, and although it wasn’t the bowlers fault the genial Rumsey was never selected again. Snow was back for the second Test, he and Cartwright replacing Brown and Rumsey. Cartwright recorded a Test best 6-94 in the South African first innings. He had just turned 30 and had another eight seasons in the county game, but he never played for England again. Snow took another four wickets but, like his team-mates, could not put the brakes on a great innings from Graeme Pollock which was the decisive factor in a South African victory. It was all change for the third Test. The selectors replaced the entire seam attack. They looked forward by bringing back Brown, and giving Lancashire’s Ken Higgs a debut, and back by giving a surprise recall to Brian Statham. Like Trueman a few weeks earlier it was to be his last Test. The old warhorse took seven wickets including a five-for but despite that England did not have enough time to square the series. Set 399 for victory they closed on 308-4.

Despite being dropped Snow had every reason to expect to be in the party to Australia in 1965/66. He was understandably disappointed when the selectors went for Brown, Higgs, Larter and a new name, Glamorgan left armer Jeff Jones. Larter’s tour was ended by injury before the first Test. To compound Snow’s anguish the replacement flown out was Barry Knight, a decent county pro who had a reasonable record in 17 previous Tests, but 11 of those had been with under strength teams visiting the sub-continent and just one against Australia. Had Snow been selected then, based on what happened when he did get to go to Australia in 1970/71, surely it would have been Mike Smith and not Ray Illingworth who brought the Ashes home.

After wintering in South Africa a fitter faster Snow forced his way back into the England side against the 1966 West Indies side with a match haul 11-47 for Sussex against the tourists on the eve of the third Test. England lost the series 3-1, and had no answer to the all round talents of Garry Sobers until, following Brian Close’s appointment as captain for the final Test, they won by an innings thanks in no small part to the unbeaten 59 Snow scored in the first innings. He and Ken Higgs put on 128 for the tenth wicket, still the highest partnership in Test cricket between numbers ten and eleven. Snow also took his share of wickets without achieving anything out of the ordinary, as he did the following summer against Pakistan and India before injury forced him to miss the final two Tests of the season. It mattered little as the selectors did not make the same mistake again. Snow was named in the party to visit the Caribbean in 1967/68.

England won the series 1-0 courtesy of Garry Sobers’ (in)famous declaration at Port-of-Spain and Snow demonstrated that he was now a world class performer. His haul for an Englishman in a series in the Caribbean, 27 wickets at 18 was equalled by Gus Fraser in 1997/98 but has never been bettered. Snow’s remains the more impressive feat as his wickets were taken in four matches, rather than the five that Fraser bowled in. Close should have been captain, but was replaced by Colin Cowdrey for disciplinary reasons and so he spent the tour in the press box. Of Snow’s performance he said He is a most deceptive bowler. At times he does not look dangerous, yet he has the ability to move the ball either way off the wicket. He can suddenly produce that extra yard of pace which has the ball ripping through to the batsman when he least expects it and he is capable of finding a little extra bounce even on the best of wickets.

In 1968 Snow met Australia for the first time and took 17 wickets in the series. He bowled well enough in Pakistan that winter before missing the third Test through injury and he took 15 wickets in the three Test series at home to West Indies in 1969. By now Ray Illingworth was England captain and, as he pushed for victory in the third Test he told Snow to bowl flat out. The wicket had no pace in it and, although England did do enough to win the match and accordingly the series 2-0, Snow disobeyed his captain and tried bowling medium paced seamers instead. Illingworth saw to it that Snow was dropped for the next Test, the first against New Zealand, although thankfully the two met in order to clear the air and Snow was back for the second and third games. In the following summer he was England’s leading wicket taker against the immensely powerful Rest of the World side that played five “Tests” against England following the cancellation of the South African tour.

Although Snow put up a superb performance in 1967/68 the highlight of his career was the Ashes series of 1970/71. He bowled wonderfully well and his 31 wickets at 22 were the biggest single factor in England’s 2-0 series win. Why did he do so well? There were a number of factors one of them being the self-evident one that, at 29 and fully fit he was, rather like Larwood in 1932/33, at his physical peak. Also like Larwood he enjoyed an excellent relationship with his captain. Illingworth was absolutely determined to return home with the Ashes and Snow was his Larwood. One of the issues that Snow sometimes had was a difficulty in motivating himself for the sort of six days a week cricket that he played in England. In Australia Illingworth expected little of him in the occasional matches he played outside the Tests – going into the first Test he had played in only three of the eight matches, bowled just 68 overs, with six expensive wickets to show for them. In the words of Cowdrey Snow saved himself for the big occasion and bowled with tremendous hostility and power when it really mattered.. It was a good job Illingworth was one of the precious few who understood what made his leading fast bowler tick – shades of Douglas Jardine perhaps?

Tony Greig did not go to Australia in 1970/71 but later on he was Snow’s captain both for England and Sussex. In 1980 he mentioned another factor in Snow’s performance; Something seems to happen to Snowy whenever he comes up against the Australians. He is not quite the same person any more – altogether more mean and hostile. – shades of Jardine again?

Snow’s ambivalence towards Australia can probably be traced back to his first match of the tour against South Australia. The mere fact that he toiled for 29 overs to take 2-166 would have been bad enough but an incident shortly before the hosts went past 600 would not have helped. Snow had Terry Jenner, whose name will crop up again later, caught behind so clearly that the tiring England side did not even bother to appeal. Jenner didn’t walk and the belated appeal was turned down. Snow was livid.

This was also the series of the spectacular falling out between Illingworth and Snow on the one hand, and umpire Lou Rowan on the other. Rowan’s starting point was There was no doubt he (Snow) had just about perfected the bouncer. He had Australia’s batsmen in all sorts of trouble.

The root cause of all the friction was that the Englishmen did not agree that what they saw as Snow’s skill in getting the ball to rear at the batsman from just short of a length was capable of breaching the laws. In Illingworth’s words Snow got chest-high bounce from only just short of a length, he got movement off the pitch but above all he bowled a beautiful line: fractionally outside the off stump, so that if the ball did even just a little bit he had every batsman in trouble. Snow was magnificent. I have never seen a fast bowler bowl better.

Rowan did not agree and kept warning Snow. Neither captain nor bowler were having any of it. Rowan wrote later of Snow Here was a man who had not the slightest intention of complying with any reasonable request or accepting any direction without an open display of hostility. And I believed he was being encouraged in this by his captain. Snow’s view of Rowan was, predictably in the circumstances I have never come across another umpire so full of his own importance, so stubborn, lacking in humour, unreasonable and utterly unable to distinguish between a delivery short of a length which rises around the height of the rib cage and a genuine bouncer which goes through head high, as Lou Rowan

The most ill-tempered match of the series was the last. Yet again there were reminders of that Jardinian winter nearly forty years previously. First of all Terry Jenner was struck on the head by Snow and had to leave the field with blood flowing from a head wound. Rowan interpreted that as a bouncer and purported to warn Snow. Snow took the view that Jenner ducked into a delivery that was about rib high. Illingworth supported his bowler. Shortly afterwards Snow was manhandled by a spectator leading to Illingworth taking the England team from the field and having to put up with Rowan threatening to treat the match as forfeited. The Yorkshireman, of course, stuck to his guns. Later still, just like 1932/33, the great fast bowler could not deliver the coup de grace as he broke a finger colliding with the picket fence while trying to take a catch in the deep.

Who was in the right? Writing about the second Test at Perth Rowan commented While the Australians were batting in their first innings I thought that, had he dared, Illingworth would have re-introduced Bodyline. Later on it wasn’t just an impression and he confirmed he became convinced of that intention. Given that the Bodyline field had been illegal for more than a decade such a comment from a Test match umpire is little short of bizarre.

But for all the Australians who looked upon Illingworth and The Abonimable Snowman in the same way that a generation before they had viewed Jardine and Larwood there were plenty who respected them. Journalist and former player Dick Whitington wrote The Snow of 1970/71 is a cricketer and character one could bracket with the malevolent Sydney Barnes, that human lasso Harold Larwood and ‘frightening’ Fred Trueman on the score of venom ……… never did he lose that aura of menace. When he loped in to bowl he wore malevolence like Mandrake wore a cloak …….. that loping, almost lazy run, is sinisterly deceptive. It is in that last stride , or last two strides, when that long, straight powerful arm gathers its impetus and either whips or coasts through, that the potential is born.

The Australian players, by and large, did not share Rowan’s view. One who did was Doug Walters but then he, averaging 97 in home Tests before the series began, was the one who was targeted most. Whenever he came into bat Snow was waiting. The tactic worked in that Walters averaged only 37 over the series, but to his credit he was only dismissed once by Snow. He later wrote that Snow bowled, in my opinion, many more than the allowable ration of bumpers…. Keith Stackpole on the other hand was rather more philosophical Snow loomed as a menace long before the tour began because, according to some observers, Australia was suspect against genuine pace. The press seized on his aggressive behaviour and built him into a big bad man. He played up to the part beautifully. He was a great bowler and there was no doubting his class. Ian Chappell, not noted himself for any lack of aggression, confined himself to On most of the occasions I’ve faced him, he has been very quick and his accuracy for a man of his pace is astonishing.

Snow himself was untroubled by the furore. He said later Because I hurled down bumpers in Test matches, I have been painted as a big bad man ….. but in some ways I’ve enjoyed the notoriety that has come with the phony image.

Back in England for the 1971 season Snow was soon in trouble with his county and was dropped for lack of effort. He was not happy with the very public way in which the matter was handled but conceded he was jaded. He missed the Pakistan series in the first half of the summer and was then in trouble again on recall for the first Test against India. India were chasing a relatively modest victory target in the fourth innings when Snow had an opportunity to run Gavaskar out. In his effort to get to the ball the two men collided sending the 5ft 4 inch Gavaskar crashing to the ground. Snow then tossed Gavaskar’s bat back to him after he had got up and dusted himself down. It looked clumsy, but certainly not malicious. When England got back to their dressing room at lunch Snow assured selector Alec Bedser that he would apologise to Gavaskar which he duly did. The apology was accepted by Gavaskar and the Indians in the spirit in which it was given and both Illingworth and Snow have subsequently written that Snow and Gavaskar had a drink together after the close of play. MCC Secretary, Billy Griffith was, however, incensed and a disciplinary hearing was convened. The British press was full of the incident for days afterwards. The measure of the true importance of what happened is best illustrated by the fact that Indian skipper Wadekar, in his autobiography that was published less than two years later, dealt with the incident in a single sentence. Gavaskar himself, in an early volume of autobiography, confirmed Snow’s apology and shared the general view that what followed was, to say the least, an overreaction. Illingworth’s view was that There was a good deal of over-reaction by just about everyone except Gavaskar.

A one Test suspension followed but Snow was still England’s leading bowler and was selected for all five Tests in the 1972 Ashes contest. For those who look for such things there was another reminder of the Bodyline series. The fourth Test at Headingley was Snow’s first game in Yorkshire since his Ashes winning efforts. In the manner of the reception that Sheffield gave Jardine on his first visit to the Broad Acres in 1933 Snow received a momentous ovation from the Yorkshire faithful.

After more than 200 overs in the five Tests against Australia Snow decided to give the 1972/73 trip to India a miss, and his Test career seemed over the following summer after he performed only moderately against New Zealand, and was then dropped after the first West Indies Test amidst concerns about his level of effort. By now Alec Bedser was Chairman of Selectors and while he rated Snow as a bowler he believed he had a negative effect on team spirit. Consequently he missed the tour to West Indies in 1973/74 and the nightmare down under of 1974/75. He was to prove later that he most certainly should have been taken back to the scenes of his two greatest triumphs.

After England’s mauling at the hands of Denis Lillee and Jeff Thomson Snow was recalled for the first World Cup and the four Tests against Australia that followed that in the summer of 1975. At nearly 34 he wasn’t quite the force of old but still took 11 wickets at 32. Snow’s last three Tests came against West Indies in 1976. He couldn’t prevent Clive Lloyd’s men making Tony Greig eat his words, but they would have been even less digestable without his 15 wickets at 28.

Late in 1976 Snow was in trouble again, firstly for wearing illegal advertising on his kit and then over the contents of his autobiography that was titled, appropriately enough, Cricket Rebel. He played a full season for Sussex in 1977 but it emerged in May that with Greig he had signed for Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, and his contract for 1978 was cancelled. The ensuing court case was resolved in Snow’s favour but he never played for Sussex again. After his time with WSC (he did not appear in any of the ‘supertests’) he made a brief comeback in 1980 when he played seven List A matches for Warwickshire. He was nearly 39 and while he failed to set the old Sunday League alight he certainly didn’t let himself down. After leaving the game Snow used the money and contacts he had acquired through his association with World Series Cricket to set up what became a successful travel agency and eventually, the dust raised by his autobiography having settled, spent some time as a Director at Sussex.

So that, briefly, is the story of John Snow’s life and times. In my view his name should be regarded as being right up there with the all time great fast bowlers. It is unfortunate that his prospects of being there were dented firstly by the number of Tests that he missed, which prevented him threatening the then Test record of Lance Gibbs of 309 (he ended up with 202) and by fate denying his reputation another spearhead with whom to share a cricketing couplet like those I mentioned in my opening paragraph. It might have been “Snow and Larter”, but the 6 foot 7 inch Northants bowler who took more than 600 First Class wickets at a cost of less than 20 runs each was finished by injury before his 26th birthday. It could have been “Snow and Jones”, but injury ended the career of Jeff Jones, England’s best left arm quick since Voce, at 26. Most tantalising of all is the prospect of “Snow and Ward”. At his best Alan Ward was every bit as quick as Snow and was the young fast bowler picked for duty in 1970/71. Just what Lou Rowan might have made of the situation if Ward had fired as well as Snow is anyone’s guess but injury ended his tour before the first Test and indeed his entire career was blighted by a succession of injuries, and he seems to have had a somewhat fragile temperament as well. I suppose that at a pinch it might even have been “Snow and Willis”, and the pair did play several Tests together prior to Wilis becoming established, but their peaks were a decade apart.

John Snow was capped 49 times between 1965 and 1976. He took 202 wickets at 26.66. Against Australia he played 20 Tests and took 83 wickets at 25.61. His best figures were his 7-40 in Australia’s second innings of the fourth Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground. Thanks to Rob Moody you can watch the whole of that magnificent performance here. Anyone who has read Lou Rowan’s book might be surprised at the bouncer count, and all will be particularly impressed by the dismissal of Rod Marsh at 15.15. Richie Benaud’s interview with Snow at the end is illuminating too. Every bit the well-spoken and articulate Englishman, but despite that Whitington’s aura of menace is clearly there, just below the surface.

I don’t think I’ve ever read an article from you that wasn’t well worth my time.

Another top effort 🙂

Comment by Neil Pickup | 12:00am GMT 2 February 2012

Another predictable article from fredfertang. Can’t he write a boring, badly researched, lazy, cliche ridden article for a change?

Comment by bagapath | 12:00am GMT 2 February 2012

I met John Snow several years back. I’m not sure why he was here. I think it may have been around the 1998-99 Ashes. Charming bloke and a real gent.

Shame he didn’t play more. Wish he was out here in 74-75. Would have been an amazing series.

Comment by Burgey | 12:00am GMT 2 February 2012

I do enjoy these profiles. Any chance of doing one about a journeyman county pro, rather than a top class international player? Someone like Mike Smith, Stuart Lampitt or Peter Smith.

Comment by HeathDavisSpeed | 12:00am GMT 2 February 2012

awesome

Comment by Hurricane | 12:00am GMT 2 February 2012

Another ripper, fred. Saw Snowy on one of those (excellent) Sky Saturday lunch docus about the 70/71 tour last year. Looks in amazing nick for a chap of his age. Made me think he could take his leather jacket off and still send down some heat.

As for the next bio, I’d vote Bill Bowes. Strikes me as an interesting chap & another from the Tyson/Snow/Willis school of atypical English fast men.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am GMT 3 February 2012

I’ve only just had the chance to read this – a really wonderful piece, Martin.

Comment by zaremba | 12:00am GMT 4 February 2012