Captain of India

Martin Chandler |

In years gone by Indian teams that visited England were no great test for the home side. With the exception of Ajit Wadekar’s 1971 side, who achieved India’s first series win in England, there was, until the 1980s, essentially a procession of teams who, whatever their perceived strengths may have been, were unable to compete effectively away from home against the full strength of England.

From 1982 onwards that situation changed, and since Kapil Dev’s side won the three Test series in 1986 by two Tests to nil, India have proved to be much sterner opponents and were successful again on their last visit, back in 2007, when a team lead by Rahul Dravid, one of seven survivors from that team who were in England this year, deservedly defeated a Michael Vaughan led England that also contained seven men who were to figure prominently in 2011.

Why then has the 2011 series reverted to the pattern of the crushing England victories of old? Although it is doubtless a factor I do not accept that the Indian side is too old. Of the senior batsmen Rahul Dravid has been as effective as ever, and while Sachin Tendulkar has not looked at his best he certainly seemed to me to fully justify his place. As for VVS Laxman he has been frustrating, but then he would not be the Laxman the cricket world knows and loves if he wasn’t, and again all the old skill looked to me to still be there.

It is a factor of course that England have played some superb cricket, but even accepting that the Indian performance really has been woeful. I like Mahendra Singh Dhoni. After never really taking a great interest in him he impressed me in the last World Cup, but I believe his captaincy has been found wanting on this tour. He has seemed unable to inspire his teammates and to lack the determination to look for weaknesses to exploit when, as has often been the case, England have been well on top. Equally on those few occasions when India were in the ascendancy he was unable to find a way to keep them there. The nonsensical incident involving Ian Bell’s “is he or isn’t he?” dismissal does not reflect very well on any of the participants, but Dhoni’s indecision is what, for me, came shining through above all else.

In recent years in particular India have produced some decent captains but, with the greatest of respect to the likes of Sunil Gavaskar, Kapil Dev, Sourav Ganguly and Dravid, their teams appeared to me to achieve the success that they did as much through sheer weight of talent as because of the way they were lead. Prior to them few Indian captains have received much in the way of plaudits for their tactical acumen and motivational skills. Even poor old Wadekar tends to be remembered as much for the abject failure of his 1974 team that toured England, than his great successes of the previous four years which, not without some justification, are usually credited as much to his predecessor, the Nawab of Pataudi Jnr, as to Wadekar himself.

Pataudi is a tiny state in the Punjab of a little over 50 square miles. It’s eighth Nawab, Iftikhar Ali Khan, played Test cricket for both India and England. He scored a century on his England debut in the first Test of the famous Bodyline series in 1932/33, but quickly fell out of favour with Douglas Jardine and by 1934 his England career was over. In 1946, aged 36 and not having played regular First Class cricket for more than a decade, he captained India in the first post war Tests in 1946. Understandably rusty Pataudi Snr failed in the Tests, but to show what might have been he ended up averaging almost 60 in the other First Class games on the tour.

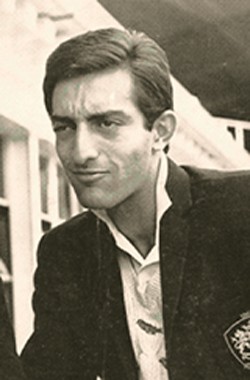

Despite the achievements of Pataudi Snr the fact that to this day the Nawab of Pataudi remains an evocative name in Indian cricket is largely because of the achievements of the ninth and, thanks to Indira Gandhi’s Government’s 26th Constitutional Amendment in 1971, last Nawab who is now known as Mansur Ali Khan. Pataudi Jnr was a fine batsman who, had it not been for his eye injury, might now be recognised as an all-time great. He was also, as he grew into the job, a captain who whist not enjoying great success in terms of results, at least brought to India a belief that they were able to compete with England, Australia and West Indies that had previously been missing.

Like his father before him, and indeed many other Indian Princes, Pataudi was educated in England latterly at Winchester. His batting abilities were clear from the start and he broke school batting records that had been set nearly forty years previously by Jardine. The Winchester coach was the old Sussex player George Cox and with Cox’s former county teammate, Hubert Doggart, on the teaching staff an introduction was made and the 16 year old Pataudi made his Sussex debut in August 1957. There were not too many runs, but his start was described as “encouraging” by Wisden in 1958. There was another modest August outing for the county in 1958 and again in 1959. Neither season produced a deluge of First Class runs for the young Nawab, but a County Championship match against Yorkshire at the end of the 1959 season was the best indication yet of his talent and temperament. Yorkshire needed to win the match in order to retain the Championship and their full side, including Test bowlers Fred Trueman, Ray Illingworth, Brian Close and Don Wilson, was on show. In a thrilling climax to the game the eventual Champions chased down 218 at the best part of eight an over. That they had to work so hard for their win was down to Pataudi, who top scored with 55 in the Sussex first innings, his maiden half century, and made a further 37 in the second innings – he was batting eighth each time.

In 1960 Pataudi went up to Oxford and played a full summer of cricket. He did well for the University and scored three centuries but thereafter was a little disappointing in the second half of the season with Sussex. For 1961 he was Captain of Oxford and, by now 20, his talent with the bat blossomed and his leadership of the side prompted Wisden in 1962 to describe his captaincy as “inspirational”. By the time his summer ended he was averaging more than 55 and had lead Oxford to three consecutive First Class victories. They had also deservedly held Richie Benaud’s Australian tourists to a draw and, Pataudi leading the way with a century in each innings, had comfortably avoided defeat against the full might of Yorkshire, the reigning County Champions.

At the beginning of July Oxford visited Hove to play Sussex and after a long day in the field Pataudi was driven back to the team hotel by the Oxford wicketkeeper Roger Waters. Three other members of the side began the journey, but had been dropped off near the hotel as they wanted to walk the rest of the way. As Waters and Pataudi drove the last few yards a car pulled out in front of them. Pataudi instinctively turned to the side and his right shoulder bore the brunt of an impact with the windscreen. Initially Pataudi was conscious only of injuries to his hand and shoulder but a sliver of glass had gone into his right eye, and despite surgery the sight in it was permanently impaired.

There was no more cricket for Pataudi that summer although he was back in the nets by August, trying desperately with Cox’s assistance to establish just what he could and could not do. He found that the hook shot was now out of the question as he simply could not follow the ball round. He also had to stop driving at balls of yorker length due to the frequency with which he was beaten, although generally he found it easier to play pace bowling than teasingly flighted spin. The new restricted Pataudi picked up the threads of his First Class career the following winter back home in India where an England side, led by Ted Dexter as in the previous summer’s Ashes series, but not at full strength particularly in its bowling resources, was due to visit for a full five Test series.

Pataudi’s first outing was a Ranji Trophy match for Delhi against a weak Jammu and Kashmir side. He scored 51 from number three in a thumping innings victory and was invited by the Board, who had not enquired about either the original injury or the progress of his recovery, to lead the President’s XI against the tourists. Pataudi began his innings using a contact lens in his right eye but to his alarm found that he then saw two balls six inches apart – at least he managed to work out that it was the inner one he needed to play at and doing so he managed to get to 35 before the tea interval on the first day. After the interval he discarded the lens and kept his right eye closed as he increased his score to 70, the top score of the innings, before falling to the right arm fast medium bowling of Kent’s Alan Brown. This match showed Pataudi’s adventurous captaincy to good effect. In an effort to force a positive result he declared twice, a highly unusual step in India at the time, and although Dexter’s men won by 4 wickets in the end there was an exciting finish.

Pataudi should have made his Test debut in the second Test but an ankle injury delayed that to the third match. He came in at 199-2 and scratched around for over an hour for 13 before being caught, trying to force the pace. He did not bat again in that match but innings of 64 and 32 in India’s big win in the fourth Test paved the way for his first Test century, 103 in the fifth Test, to help India to a second successive victory and a famous series win. The innings took well under three hours and contained eighteen boundaries, two of them sixes. This knock was particularly memorable because of the manner of Pataudi’s batting. Since Vijay Merchant’s day Indian batsmen had been coached never to hit the ball in the air. Pataudi ignored that old mantra and repeatedly hit the ball over the infield and indeed did so with such effect as to persuade his captain, Nari Contractor, a batsman who could be as defensive as anyone, that over the top was the right route, as they put on 104 together. By now Pataudi had worked out how best to deal with his handicap, pulling the peak of his cap down over the right eye to prevent the double image. He did experiment with an eye patch that made him look like a swashbuckling buccaneer, but found that shutting all light out of his damaged eye was counter-productive.

After his performances in the final two Tests against England Pataudi’s selection for the tour of West Indies that followed on shortly afterwards was assured. What was rather more surprising was that the 21 year old should be appointed vice-captain and inevitably a number of more senior and, on the face of it, better qualified men were passed over. That said the decision was an understandable one. As noted already Pataudi showed immense promise as a captain in 1961 and, given that Contractor was only 27, there was no expectation that he would actually be called upon to lead for some time. That line of reasoning was, naturally, asking for trouble and Contractor received a sickening blow on the head from Charlie Griffith in the Indians’ fixture against Barbados the effects of which were so severe that his International never resumed. Pataudi acceded to the captaincy of a side thoroughly demoralized by defeats in the first two Tests, for which he himself had not been selected, and then the loss of their leader in such dreadful circumstances. He was the youngest Test captain the game had seen, a record that stood until Tatenda Taibu took charge of Zimbabwe aged just 20 in 2004.

There was little Pataudi could do to halt the slide to a 5-0 defeat although he did score a couple of 40s, and perhaps more importantly seemed to command the respect of his teammates and in particular the hugely experienced Polly Umrigar, who might well have expected the captaincy to devolve upon himself given the circumstances. Umrigar, a gifted batsman although one generally not too keen on quick bowling, was sufficiently inspired to play an innings in the fourth Test which, if it did not change the character of the series, at least showed his younger colleagues what could be done.

India met England again the following winter and Pataudi was captain once more albeit, initially at least, only by virtue of the casting vote of the Board Chairman. The feeling of insecurity that he felt, coupled with his own wretched form in the first three Tests, no doubt led to the uninspired captaincy that he displayed as his team gathered their runs slowly and he failed to attack an England side that was never, due to illness and injury, able to fire on all cylinders. The fourth Test saw a sea change however. Pataudi at last ground out some form scoring a century and then, against some part-time bowling, going on to make it a double. He himself always acknowledged that it was almost certainly the least impressive double century ever scored in a Test, but it secured his place and awoke the adventurer in him. In the final Test Pataudi won the toss and invited England to bat. There was no reason, other than doing something unconventional for the sake of it, for that decision, which backfired anyway as England enjoyed a productive day but, the Board having refused to allow Pataudi to negotiate a fourth innings challenge with England captain Mike Smith, they could hardly then criticise him when the match, as with the first four, was left drawn.

In 1964/65 Australia visited India. Unlike England Australia always sent its strongest side to India and there was no expectation of victory amongst the Indian press or public, and the first of the three Tests resulted in a comfortable Australian victory. The home supporters thoroughly enjoyed the match despite the defeat. They saw their team collapse in the first innings, only to then witness Pataudi himself, with an unbeaten 128, lead a recovery that saw India take a first innings lead before the Australian batsmen restored order in their second innings. Pataudi played a leading role in the second Test as well. A relaid wicket at the Brabourne Stadium was rather less docile than the old strip. Again Australia seemed to be in command until Pataudi, with 86, many of them scored by taking the aerial route, helped to coax 160 out of the last five wickets to take another first innings lead. Chasing 254 for victory India slumped to 122-6 before 53 from Pataudi was the major reason why the target was reached with two wickets to spare, and with it a first ever victory over Australia. It was a great shame that rain washed out the last two days of the final Test, India having secured a first innings lead for the third time in the series in the three days play that were possible.

Later that season New Zealand visited for a four Test series. It has to be conceded that although Pataudi the batsman was on form his captaincy lacked its usual enterprise and, by delaying his declaration in the third Test to allow Dilip Sardesai to get to 200, he certainly cost India the game. They did however win the final Test and the series so, perhaps a little fortuitously, Pataudi’s reputation as a captain emerged unscathed. The next big Test was at home against West Indies in 1966/67. Pataudi had banished forever the days when Indian batsmen were scared of pace bowling but the series was lost 2-0. The visitors comfortably won the second Test by an innings but if important catches had been held India would have won the other two Tests and their progress under Pataudi’s impressive captaincy continued.

In 1967 it was back to England and, sadly for India, a 3-0 defeat in the three Test series. In mitigation the tour was poorly managed and heavy rain in May meant that conditions were generally damp and wholly unsuited to India’s bowling strength, her famous spin quartet. Despite this there were some highlights for the visitors. In the first Test at Headingley, despite a valiant 64 from their captain, India were all out for 164 to concede a first innings deficit of 386. Following on Pataudi scored a fine 148 as India powered to 510. Given that both Rusi Surti and Bishen Bedi had been injured and could bat only with the assistance of a runner Pataudi was not very far away from achieving a remarkable escape. The second Test was very much a case of “after the Lord Mayor’s Show” as India lost by an innings despite England reaching only 386. In a different time India would have packed their side for the third Test with batsmen in the hope they might thereby avoid defeat. Pataudi however played all four spinners, the only time they appeared in a Test together. His batsmen could not do enough to avoid defeat but at least the team selection was vindicated as the bowlers dismissed England twice, for 298 and 203, the only time in the series that they took 20 wickets.

Ironically Pataudi’s most remembered series is probably the 4-0 defeat in Australia in 1967/68. India did not record a single victory on the entire tour, but they played their part in an entertaining series and squandered strong positions in both the third and fourth Tests. Pataudi was injured early in the tour and missed the first Test. He played in the second, although still so lame his fielding and running between the wickets were seriously effected. Having won the toss and decided to bat, a decision later to be used against him when the captaicy was taken away from him, Pataudi found himself at the wicket at 25-4, McKenzie having taken four quick wickets. Innings of 75 and 85 by the, to all intents and purposes one-legged Indian skipper, thrilled the crowd at the MCG although an innings defeat duly followed. In the next Test Pataudi was still struggling but his innings of 74 and 48 helped India get within 39 runs of Australia. In that Test particularly, but also in the fourth and final game where Pataudi recorded another half century, dropped catches cost the Indians dearly.

The four match series that followed in New Zealand was an altogether easier proposition and India won 3-1 to record their first series victory overseas. It probably should have been a clean sweep, but in a strange decision Pataudi chose to invite New Zealand to bat in the third Test, and watched them pile up more than 500 in what proved to be a comfortable victory for the home side.

Two years later New Zealand and then Australia visited India and this was the beginning of the end of Pataudi’s reign. The three Test series against New Zealand was drawn 1-1 and indeed India very nearly lost the deciding Test. Cricketing opinion began to move against Pataudi as some of his more eccentric decisions were now closely examined. In addition he received the blame for his players not having a killer instinct, the absence of which was blamed for the poor showing against New Zealand. It did not help that with the exception of 95 in the first innings of the first Test against Australia (a five match series that was lost 3-1) Pataudi struggled for runs himself.

Outside the game it cannot have been irrelevant that Pataudi, as a Royal Prince, was in the process of having his privileged status removed by Indira Gandhi’s legislature. Perhaps it was relevant that he was a Moslem from the north of the country, although I have seen nothing more than oblique references to that as a factor. What certainly did happen is that Pataudi, still only 29, lost the captaincy to Ajit Wadekar for the 1970/71 tour of West Indies on the casting vote of the Chairman of Selectors, the revered Vijay Merchant.

From a distance of more than forty years it seems most odd to this writer that Pataudi should have been passed over in this way, particularly by Merchant, a man who wrote him a glowing tribute just a few years later. The reason appears to be rooted in an incident described by Merchant in his tribute as “famous”, although I suspect he may well be the only man who has thus described it. The issue surrounded team selection for the first Test against Australia. The selectors named their eleven, without a twelfth man, before the match and replaced off spinner Srinivas Venkataraghavan with the undistinguished right arm seam bowler Subrata Guha. Reading between the lines it seems likely that Pataudi simply refused to accept the team he was given, the selectors thereby having to perform an embarassing volte face and reinstate Venkat at the expense of Guha. In future India’s selectors gave up the practice of naming their final eleven in advance, and it seems likely that this perceived snub is what lay behind Merchant’s decision to, effectively, sack Pataudi.

Having lost the captaincy Pataudi did not make himself available for either the West Indies or England tours. He had initially told Wadekar he would tour but quickly changed his mind and decided instead to stand in the 1971 General Election. He was, not unnaturally, opposed to Mrs Gandhi’s Congress party’s reforms and he stood against them. It seemed his Test career might be over, but by all accounts, including his own, he did not put too much effort into his campaign and he received less than six per cent of the vote.

In 1972/73 Pataudi was in the press box for the first two Tests to watch India unexpectedly lose the first, and then win narrowly in the second against Tony Lewis’s England. Prior to the third Test he scored a century against the tourists for South Zone and he subsequently agreed to play under Wadekar in the third Test. It was just as well for India that he did as without his 73 in their first innings they would almost certainly have lost, rather than win what proved to be the decisive match of the series. The reception he received as he came out to bat at 89-3 was a tumultuous one and clearly for the nation, if not all the administrators, whatever issues there may have been in the past were forgiven and forgotten.

Attempts were made to persuade Pataudi to tour England again in 1974 but he declined. For Wadekar that tour was one too far given the unexpected 3-0 reverse. A huge groundswell of opinion rose up to reinstate Pataudi as captain at home against West Indies in 1974/75. He indicated he would take up the reins again but, understandably, only if asked to do so on the basis of a unanimous decision from the selectors. Consensus was duly reached and the invitation accepted. India lost the first two Tests, the second of which Pataudi missed through injury, but won the next two to set up a deciding Test in Bombay. Sadly the match resulted in a heavy Indian defeat, but much was decided by the initial toss of the coin. Had Pataudi been able to choose to bat first, and condemn the West Indians to taking fourth innings against his spinners, or even if a chance offered by Clive Lloyd when 8 had not been spurned (he went on to make 242*) then India might have matched the achievement of Donald Bradman’s 1936/37 Australians of coming back to win a series after going 2-0 down.

For Pataudi the batsman the 1974/75 series was a series too far as he averaged just 13. He had never, since his accident, been at his best against top class spin bowling and Lance Gibbs tormented him all series. All his old bravery against pace remained, but the one eye wasn’t as quick as it had once been and a young Andy Roberts caused him as much trouble as Gibbs. Despite his failure to contribute with the bat, or perhaps because of it, it was generally recognised that the series saw his captaincy at its best. One respected observer, PN Sundaresan, commenting that he was worth a place for his captaincy alone – in any event as Mihir Bose pointed out in his History of Indian Cricket Pataudi’s was always a name more associated with heroic performances that ultimately failed, rather than glorious successes.

Since retiring from cricket Pataudi has led an interesting life. In 1969 he had married a well known actress and two of his three children have found fame in Bollywood. In 1991 he decided to dabble in politics again, except this time rather than oppose the Congress Party he was their candidate. The adventure was rather more successful this time, Pataudi polling just under 36 per cent of the vote, but he still came second. He has also been involved with the ICC and was their Match Referee for two of the Ashes Tests of 1993. More recently still he played a role in the early days of the IPL, with whom he eventually fell out to such an extent that litigation followed.

His interesting life outside the game notwithstanding the abiding memory of Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi is of a cricketer who threw off the shackles of defensive batting and captaincy in India, and who paved the way for others to take them, albeit briefly, to the summit of the world game. How good a batsman he might have become had he, with his three teammates, decided to walk the last few yards back to his Brighton hotel on that fateful evening in July 1961, is one of the game’s great “what ifs”, but I suspect he might have bestrode Indian cricket then much like Sachin Tendulkar does now. His spirit of adventure and desire to set up winning positions might, I suppose, have still meant that he did not rewrite too many batting records, but India today could certainly use an injection of the sort of enthusiasm and fresh ideas that he brought to the job when he was captain of his country.

Excellent article. Reads well-written and well-researched.

Comment by G.I.Joe | 12:00am BST 27 August 2011

I thought the article would be about Dhoni :p……but looks good from what I have read so far

Comment by smalishah84 | 12:00am BST 27 August 2011