Fire in Babylon – The Prelude

Martin Chandler |

We have just seen one of the more low key Test series of recent times played out in the Caribbean. For the Indians an experimental side were sent out to play a home side who are a mere shadow of the great West Indian sides of the not so distant past. It has to be conceded that some interesting cricket has been played and the hosts have, perhaps, demonstrated that they may have started to turn a corner, but overall the tour is not one that will linger long in the memory. It is all a far cry from the 1975/76 season when the two sides were involved in one of the more competitive, and acrimonious series the game has seen.

In 1970/71 India had won a five match series in the Caribbean 1-0. A young Sunil Gavaskar, playing in four of the Tests, had shot to prominence by scoring 774 runs at 154.80, with four centuries and three half-centuries. The Indians had gone on to defeat England home and away in 1971 and 1972/73, and while they had fallen back again with a 3-0 defeat in England in 1974 they were still a strong side. For West Indies the great Sobers had retired after the drawn home series with England in 1973/74, and Clive Lloyd was looking to build a team of worldbeaters.

Lloyd had started his reign during the previous winter of 1974/75 in India when a see-saw series saw his men take a 2-0 lead, before being pulled back to 2-2 to set up an intriguing final Test, when a comfortable West Indian victory was a result that proved a little disappointing to the neutrals.

After such a promising beginning, reinforced by victory in the first World Cup in the English summer of 1975, Lloyd’s plans had however suffered a huge setback just a few weeks before the 1975/76 series against India was due to begin as Greg Chappell’s Australians, with home advantage, defeated his young side 5-1. The manner of the defeat had hurt as much as the unflattering scoreline, the West Indians being in a state of some disarray by the end of a series they had begun with high expectations. Their performances in Australia would, later on that year, be cited by England Captain Tony Greig to back up his infamous “grovel” comment.

The first Test of the series against India took place in the West Indian stronghold of Barbados, where they had not been defeated since 1935. The match was over in three days as the home side recorded a resounding innings victory. The 21 year old Michael Holding played his first home Test, and there were a couple of wickets each for him and Andy Roberts as India batted first, but the main wicket taker, unexpectedly, was Garry Sobers’ cousin David Holford. There were 24 Tests for Holford over a ten year period but he was something of a peripheral figure in Caribbean cricket, and was never entirely sure of his place. In this match however his leg spin brought him a haul of 5-23 in just 8.1 overs. It was his first, and only, five wicket haul at Test level. India were all out for 177.

West Indies’ response was dominated by a young Viv Richards who, despite playing in 13 previous Tests had, like Holding, not previously appeared before a home crowd. Richards made 142 and Lloyd also reached his century. Alvin Kallicharran weighed in with 93 and Lloyd was able to declare on 488. India performed a little better second time round, but never looked like making their hosts bat again.

It was on to Trinidad for the second Test just over a week later. This time it was West Indies who batted first, after being invited to do so, but although there was another fine knock from Richards, 130 this time, none of his teammates could emulate him and his side were all out for 241. For India it seemed to be a similar story as Gavaskar regularly lost partners until, eventually, newcomer Brijash Patel stuck with him and these two, who both scored centuries, were the main reason behind Bishen Bedi being able to declare at 402-5. Bedi would doubtless have preferred a few more runs, but the first day had been lost to rain. In addition Patel, as he neared his century, and Madan Lal were unable to take the bowling by the scruff of the neck in the couple of hours before the declaration. With just over a day left Bedi could not realistically delay the closure any longer than he did. When the game finished the home side had cleared their deficit, but were only 54 ahead with just two wickets to fall. Lloyd had played a fine knock of 70 to hold India at bay but he had been fortunate. On 27 he had hit the ball in the air between mid off and extra cover who collided as both went for the ball, and what should have been a straightforward catch went to ground.

There was an incident in the West Indies second innings that doubtless had some bearing on later events. When Richards came out to bat, after his two centuries in his two previous innings in the series, he was clearly in some difficulty with a foot injury. He tried to bat on but after a few minutes there was a considerable delay and earnest discussions involving both captains and the umpires before Richards returned to the pavilion. Initially it was believed, and widely reported, that Richards had asked for and been denied a runner, as on the letter of the law Bedi would have been entitled to do on the basis the injury was a pre-existing one. It was later announced by the Indian camp that what had happened was that Richards had asked to retire hurt. Bedi had agreed but had sought to invoke that part of Law 33 that allowed him to then dictate when Richards could resume his innings, which he wanted to be at number 11. Lloyd was unhappy, and expressed the view to Bedi that not even the Australians played the game in such an inflexible manner. As things turned out Bedi did bend, and Richards came in at the fall of the fourth wicket, but the incident was certainly not forgotten, although the detail clearly has in some quarters as Holding for one, although he would not have been involved in the on field discussions, has maintained that the bone of contention was a refusal by Bedi to permit Richards a runner.

The third Test was due to be played in Guyana but torrential rain, and the refusal of the Jamaican authorities to swap the third and fourth matches, meant that in the end everyone ended up back at Port-of-Spain in Trinidad. The home side, doubtless noting the success of the Indian spinners in the second match, selected three specialist slow bowlers themselves in off spinner Albert Padmore, orthodox slow left armer Raphick Jumadeen, and local wrist spinner Imtiaz Ali. The two pace bowlers were Holding and the left arm fast medium all-rounder Bernard Julien. Subsequent events meant that Lloyd never placed his faith in spin again.

West Indies won the toss and batted. A fully fit Richards scored another century, a fine 177, and Lloyd contributed 68, but the rest of the batting failed and after a breezy 47 from Julien the last five wickets fell for just 24 and the eventual total of 359 was a disappointment to the local crowd. In reply all of the Indian batsmen made a start, but only Gundappa Vishwanath and all rounder Madan Lal got past forty and India conceded a lead of 131. Holding took 6-65 in 26.4 overs. The spinners took just three wickets between them in their combined 62 overs.

In their second innings just one West Indian batsman, Alvin Kallicharran with 103, made a major contribution, but only Julien was out for less than 23 and Lloyd was able to declare on 271-6 leaving India around nine hours to score 403 for victory – only Don Bradman’s 1948 “Invincibles” had previously made more than 400 in the fourth innings to win a Test match. In the press box were many shrewd observers of the game, some former players, and there were no suggestions at the time that the declaration was too generous. In fact Lloyd was not immune from the criticism that he had batted on a little longer than he needed to.

The scorecard suggests the target was an easy one as India proceeded to win by six wickets and indeed, thanks to centuries from Gavaskar and Viswanath, and a fine 85 from Mohinder Amarnath, it did not prove too difficult, even if for a period in the afternoon Lloyd’s defensive tactics did at least succeed in giving India a few concerns about running out of time. In the end however the standard of ground fielding did fall off and when the winning hit was made by Patel there were still seven overs left.

Not unnaturally the Indians celebrated long into the evening following their famous victory. There was still however one slightly unsavoury episode as the three Indian journalists who were accompanying the tourists were denied the opportunity to participate in the celebrations. The ill-feeling seems to have gone back to the second Test where all three had sent interval reports back home suggesting that Richards had been refused a runner in the second Test, and their subsequent filing of revised copy once the Indian management had issued a statement to the effect that the reality of the situation was different, was too late to stop the original story being published.

In a 1980 volume of autobiography, “Living for Cricket” Lloyd said I am sorry to say the spin trio was just not up to it. For the fourth and final Test in Jamaica the home side omitted Padmore and Ali and replaced them with a 19 year old debutant, Wayne Daniel, and the experienced Vanburn Holder. Daniel was genuinely fast, and a class act, and in any other era would surely have been capped many more than ten times. Holder was a pace bowler too. He was not as quick as Holding or Daniel, but was no slouch, and if necessary could summon up plenty of aggression.

In the 1970s the wicket at Sabina Park was second only to Perth in terms of pace although, unlike the WACA, it slowed down as matches wore on. When therefore, in good batting conditions, Lloyd won the toss and asked India to bat it was obvious he intended to seek to exploit the pace in the wicket, and that the Indians were in for a torrid time in a match which, as it was to decide the series, had had a sixth day added.

On the first day Lloyd’s pace battery certainly troubled India but, despite each of Gavaskar, Anshuman Gaekwad and Amarnath having some difficult moments when persistent drizzle ended the day part way through the final session only Gavaskar had been dismissed and India were 175 runs to the good. With the prospect of facing Bedi, Chandrasekhar and Venkataraghavan in the fourth innings Lloyd had problems and a series that had looked there for the taking after the victory in the first Test now seemed to be slipping away.

As the second day dawned there was no indication of the carnage that was to come as Julien and Holder opened up in order to while away a few overs before Holding could take the new ball. At 199-1 Holding took the cherry and suddenly the game changed. Holding had clearly been instructed to bounce out the batsmen and Holder, a man for whom guile rather than blitzkrieg was generally the weapon of choice, was also bowling consistently short.

At 205 Amarnath could not avoid a Holding bumper and gave Julien a straightforward catch at backward short leg. At 216 Viswanath was dismissed in similar fashion, and to add insult to injury he was to play no further part in the match as a finger was broken by the Holding thunderbolt. Shortly after lunch Gaekwad, who had been hit a few times already, was finally struck on the head and he too was out of the game. Patel replaced Gaekwad and batted bravely but he could not hook well, and was not used to such high speed, and it was only a matter of time before a lifter, this time from Holder, struck him in the face and he too retired hurt, unfit to return.

Madan Lal did not last long and when Vengsarker, who decided to weave rather than duck and did so with some success for 39 runs, lost his leg stump to Holding, and Venkat immediately fell to Daniel, Bedi declared the innings closed at 306-6 – there was no point in his and Chandra standing in the firing line given what must have seemed an overwhelming risk of serious injury. The Indians were furious. Both Bedi and Gavaskar had taken the umpires to task about what they saw as being a clear breach of Law 46 (intimidatory bowling) but neither umpire was prepared to even speak to Lloyd let alone intervene.

There was talk from the West Indians, and Lloyd in particular, of a ridge at the end Holding was bowling to, but the Indians, taking into account that the ridge was not evident on the first day, and also that a number of overs of short pitched deliveries that the tall right handed Gaekwad in particular had to endure from Holding were delivered from round the wicket, had no doubt that the West Indians did not care how batsmen were removed, as long as they were. The man best placed to comment on the existence or otherwise of a ridge was Holding himself. In 1993 he wrote Some people claimed there was a ridge but I never detected one. A few sentences later he admitted to aiming at the batsmen’s bodies while bowling round the wicket explaining …. it was 1-1 in the series and, after Australia, we were under extreme public pressure to win. Holding was, of course, adopting that line to force the batsmen to play the ball and, hopefully, produce a catch for the close fielders, but the fact remains that their only alternative to attempting to put bat on ball was to risk serious injury.

Despite their anger the Indians remained focused and although the West Indian top order got them to 186-1 the run out at that point of Roy Fredericks, followed by Chandra removing the middle order in quick time, meant that the home side were in trouble at 217-6. That they got to 391 and a lead of 85 was thanks in large part to Holding’s first Test half century, as he and wicketkeeper Deryck Murray put on 107 for the seventh wicket. There was some more evidence during the early part of the West Indies innings of the two team’s antipathy towards each other as the West Indies objected to one of the Indian substitute fielders, Eknath Solkar, taking up his specialist position at short leg. That Solkar was a magnificent fielder, particularly in the leg trap, is not in doubt, but given the sure and certain fact that the Indians would have no more than eight men to bat in their second innings it seemed a somewhat churlish demand.

With just three specialist batsmen to come out in their second innings it was all that a demoralised India could do to limp past the 85 they needed to make the home side bat again. The pitch was suddenly docile again, with no evidence of the ridge of the second day, but wickets fell regularly and it was only an uncharacteristically aggressive innings from Amarnath that took India into the lead. When the third, fourth and fifth wickets all fell on 97 there was a bizarre moment as the not out batsman, wicketkeeper Syed Kirmani, waited in vain in the middle before realising that he was the last man standing and that the innings was closed. Initially it was recorded as a declaration although it was later announced that both Bedi and Chandra had sustained hand injuries in attempting return catches in the West Indian innings. The home side needed to score just 13 runs to take the series.

Bedi did not take the field for those two overs and said later at a press conference, without mentioning any injury, that he had been …in no mood to observe the formalities. Only later was it confirmed that he had a fractured finger. Chandra, who was in plaster up to the elbow, was clearly injured. The West Indies second innings consisted of only two overs. The first was bowled, as usual, by Madan Lal, perhaps a tick over medium pace. He let Lawrence Rowe have at least five bouncers – six on Mohinder Amarnath’s account. The Indians’ point made the second over was bowled by Vengsarker – he got through five of the 47 deliveries he was to send down in his 116 Tests before the winning runs were scored.

Bedi was furious at the way the West Indies had bowled and took every opportunity to say so. Lloyd, the man in the firing line, has always been defensive about the tactics he used. In the 1980 autobiography from which I have quoted above he went on to say …. the Indians unfairly blamed us for their own deficiencies and attempted to decry our win. Five years later Lloyd was the subject of a biography by Trevor MacDonald. He was no more forgiving then telling MacDonald It was never and has never been our deliberate policy to indulge in unfair tactics ………..they (India) talked about barbarism and all that stuff, I cannot accept that……… their batsmen simply couldn’t cope …. if you can’t play quick bowling you shouldn’t be in the game at international level . One might have expected a little mellowing by 2007 but not a bit of it. Lloyd’s second biographer, Simon Lister, quotes him as saying The indian tactics were not exactly a show of guts and later ….any talk of intimidatory bowling is false – a false accusation..

Lloyd did have some justification for his anger. Gavaskar, in a passage from an early volume of autobiography, “Sunny Days”, made the inflammatory comment, when dealing with the vocal encouragment given by the locals to their quick bowlers, All this proved that beyond a shadow of a doubt that these people belonged to the jungle and forests instead of a civilised country. It has been suggested by some that Gavaskar’s subsequent refusal to tour the West Indies in early 1981 was motivated by concern at the reception he might receive after that comment rather than, as he announced at the time, a feeling of being jaded as a result of a full English season with Somerset. Whatever the main motivation was in that decision the proposed tour was ultimately cancelled, and albeit with rather less success than on his two previous visits Gavaskar did return to the Caribbean for a full series in February and March 1983.

In 1993 Chandra’s biographer only dealt with the third Test, prefaced by the comment from his subject This was a Test in which our batsmen did us proud, and because of that we had that terrible bloodbath in Kingston. Unlike Lloyd Gavaskar did mellow and after that 1976 outburst he was magnanimous enough to devote a chapter, entirely complimentary in content, to Lloyd in his 1983 book “Idols”. In 1996, in a lengthy article in his benefit publication “Grit and Grace”, Mohinder Amarnath, even went so far as to express the view he considered the West Indian tactics to be legitimate. He acknowledged the enormous pressure on Lloyd to deliver after the defeat in the third Test and the unsuccessful first day at Kingston, and he even went so far as to contradict Holding and say there was a ridge.

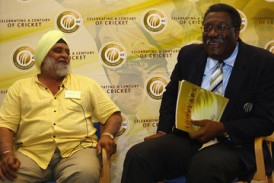

As for the Indian captain it was inevitably the case that a man who so valued fairness in the game would harbour strong feelings about what occurred at Sabina Park in the final Test. It is, sadly, the case that Bedi is probably the most interesting cricketer never have to written an autobiography or had his biography written by someone else. I hope one day that that omission will be put right but in any event in July 2009 he and Lloyd were photographed together, clearly at ease in each other’s company, at an ICC Centenary History Conference in Oxford, so it seems that after more than 30 years the two captains, inevitably the men most affected by the controversy, had buried the hatchet.

Wisden made the comment in its 1977 edition that, as they boarded their plane home at Kingston Airport, the bandaged Indian tourists resembled Napoleon’s troops on the retreat from Moscow. It is understandable in some ways that Lloyd expressed the views that he did at the time, but perhaps less so that he did not reconsider them for so long with the passage of time. The Indians were not, it has to be accepted, as familiar as some with dealing with extreme pace given the dominance of slow bowling in their domestic game, but they were certainly not scared of fast bowling nor were they technically unable to deal with it. Viswanath in particular was universally recognised as a particularly fine player of pace bowling and the Indian top order batsmen, without exception, played with great courage throughout the series. Gaekwad for example, whose injury at Kingston resulted in him spending three days in hospital, needed a direct order from the Tour Manager, former Test batsman Polly Umrigar, to make him accept that he would not be resuming his innings.

The release recently of “Fire in Babylon”, a celebration of the great West Indian sides of the 1970s and 1980s, may well create renewed interest in the 1975/76 series and its aftermath. Many who take an interest will probably not appreciate that the pace revolution came so close to not happening, at least in the manner and at the speed it did. The West Indies did come close to losing the series and indeed had only the weather to thank for not being 2-1 down going into the final Test. Following that 5-1 defeat in Australia it must be likely that had this series been lost too, particular if the Indian batsmen had been as successful on the second day at Kingston as they had on the first and the margin had been 3-1 to India, that Lloyd would not have been retained as captain and that his four pronged pace attack might never have taken the field again. Perhaps most important of all though is that Bedi’s tourists are remembered for what they were – a team of courageous and skilled cricketers who, for want of the sort of protection that in the future would become the norm, both in terms of equipment and eventually the interpretation of the laws of the game, only just failed to record a famous victory.

Brilliant article, well researched and well written. I enjoyed it hugely.

I remain ambivolent about both parties. Bedi was no stranger to having a very public moan of course, as we saw 9 months later when John Lever was so successful in India. Perhaps he felt the pressure of his side slipping from their position in the early 1970s and the public criticism he was likely to face as a result. As for Lloyd, Sabina Park was hardly the only occasion when his statesmanlike captaincy amounted to doing not a thing when his quicks overdid it or, as in NZ four years later, completely lost the plot.

One question – when researching this piece, did you come across any references to several beamers as well as the short-pitched stuff in the Jamaica test? I remember reading about that somewhere, and, for me, it puts a whole different slant on matters from the line that the Indians simply didn’t want to get in line against the bouncers.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 12 July 2011

I recall hearing about beamers as well and I did find the odd reference to them while I was going through various books, although not anywhere I felt was particularly authoritative

As far as the actual play is concerned as well as the books by or about the various participants there was an account of the tour published in India which was very helpful and, I felt, very fair. The author (a bloke called Kishore Bhimani who was one of the three journos following the team round) was clearly unimpressed by the WIndies tactics but he made no mention of beamers and I felt sufficiently sure he would have done had there been any not to need to refer to the issue.

It’s actually amazing just how different accounts can be. I did read somewhere that Madan Lal was told to and did bowl a beamer in that over in the WIndies second innings, and the Viv Richards retiring hurt/runner incident has almost as many versions as there are people who have written about it

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am BST 12 July 2011

Fascinating read. The 70’s and 80’s had a good amount of entertainment I’d say.

Comment by Himannv | 12:00am BST 12 July 2011

I think a bit of context is needed here….

1) Thomson and Lillee had just brutalised the Windies batting, sending quite a few of them to hospital, and the Windies took it basically without complaint. Lillee and Thomson bowled to deliberately hurt the batsmen, so Lloyd realised that this was a legitimate tactic, and used it against the Indians at Sabina Park.

2) This passage you quoted from Gavaskar’s book gives an idea of the antipathy that existed between the teams: “Gavaskar, in a passage from an early volume of autobiography, “Sunny Days”, made the inflammatory comment, when dealing with the vocal encouragment given by the locals to their quick bowlers, ‘All this proved that beyond a shadow of a doubt that these people belonged to the jungle and forests instead of a civilised country.'”

3) Michael Manley was present at the match, and he made this observation about Gaekwad’s injury in ‘The History of West Indies Cricket’. “Gaekwad’s injury was exactly a replay of England’s captain, Bob Wyatt, facing Martindale forty-one years before on the same ground and batting at the same end. Both the England captain facing Martindale and now the Indian batsman facing Holding assumed a ball of great pace would lift. Both ducked. Neither ball lifted and both might have been killed. Happily both survived.”

4) “Vishwanath had suffered a broken left hand when caught at leg slip off Holding.”

5) “The case of Patel was completely different. He jumped down the wicket to hit Holder out of the ground and, having taken his eye off the ball, it flew from the top edge and he was struck in the mouth. At this stage Bedi declared to ensure that neither he nor Chanderasekar would have to face the bowling.” Let’s not forget that Vanburn Holder was little more than a medium pacer….

6) “Bedi and Chandrasekar had hurt their hands attempting return catches during the West Indian innings.”

7) In his autobiography, Holding says that on reflection, he felt that their tactics were not in the right spirit of the game, and that they shouldn’t have bowled around the wicket to the Indians.

8) Lloyd is understandably unapologetic in his biography by MacDonald: “We had a whole lot of problems, but the main one was that our batsmen were frequently exposed to Lillee and Thomson, still fresh and still raring to go with a relatively new ball. Our players all round were put under constant pressure by sheer pace on some very quick wickets. And many of us were hit. I had a double dose. I got hit on the jaw by Lillee in Perth and by Thomson in Sydney. Julien’s thumb was broken, just when we felt he might help solve the problem about our opening batsmen; Kallicharran’s nose was cracked by Lillee in Perth and everyone at some stage during the tour felt the discomfort and the pain of a cricket ball being sent down at more than ninety miles an hour. But that’s the game. It’s tough. There’s no rule against bowling fast. Batsmen must cope to survive.” Basically, Lloyd’s saying the WI put up with this in Australia, so they were just dishing it out to India, and you can see the logic.

Comment by shivfan | 12:00am BST 12 July 2011

Just went through your article Fred…………all I can say is fantastico

Comment by smalishah84 | 12:00am BST 12 July 2011

Wasn’t Gavaskar’s comment written after the series in question? I’m not saying that justifies it – only that it couldn’t have contributed the WI approach at Sabina Park.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 13 July 2011

Personally I have no problem with the tactics the West Indies adopted and I don’t think the piece suggests that I do. Cricket history is littered with examples of the team without fast bowlers complaining about those who do but, like Larwood/Voce, Lindwall/Miller, Hall/Griffith, Lillee/Thomson and the like as long as the quicks operate within the law then to my mind that must be legitimate.

What I do think is unfair and is quite clearly wrong is to question the courage of the Indian batsmen.

………. and yes “Sunny Days” was published after the tour ended – but not long after so it was doubtless still a little raw – the relevant chapter was titled “Barbarism at Kingston” – as I said in the piece it was understandable Lloyd was unhappy

Comment by fredfertang | 12:00am BST 13 July 2011

Excellent article, fred. Up there with your best, which is no small praise. 🙂

As a kinda related aside, I’ve always felt slightly let down by David Frith’s mildly sniffy attitude to the Windies’ quicks. They may have gone over the line on occasion, but Frith seems to struggle to see the wood for the trees on this topic.

Shame because he’s otherwise my favourite cricket writer.

Comment by BoyBrumby | 12:00am BST 13 July 2011

Fabulous piece, Martin – a wonderful read!

Comment by Dave Wilson | 12:00am BST 13 July 2011

I can personally vouch for the fact that Wayne Daniel bowled beamers on his debut and then would look at his hand as if the ball had slipped. I watched the highlights on TV as a schoolboy in Calcutta in the presence of the late Dattu Phadkar, a swing bowler all rounder of the 40s and 50s. He repeatedly commented on the beamers. One of the brothers of one of the Indian team members told me last week that the WI quicks also bowled deliberate no balls, but the local umpires refused to step in for fear of crowd violence. And yes, in retaliation Madan Lal did bowl a couple of beamers in the WI second innings out of frustration which is a bit of a joke considering his gentle pace. Of course the joke was on the WI batsmen 7 years later at Lords in the Prudential World CUp final when Madan and Mohinder destroyed them with their gentle swingers. Retribution for Kingston 76 no doubt!

Comment by Gulu | 12:00am BST 16 July 2011

Fire in Babylon – The Prelude made for gripping reading, and I sat on the edge of my chair until the last word was consumed – the taut narrative tickling the adrenals, as the article climaxes in the controversial Kingston Test. Though the decider of the series in Jamaica takes centre-stage in the story, and quite rightfully so, an appropriate background to the series has been provided: in the form of allusions to the closely fought India-West Indies series of 1974-75 and the Australia-West Indies series of 1975-76. The spirited Indian response in the second and third tests of the ’76 series, as also the various incidents that could have contributed, if not actually fuelled, the final denouement in the fourth test have been placed in appropriate contexts. The highlight of the article, however, is its objective narration of the versions of the main protagonists – as they saw it then, and as they see it now. Lloyd stands by his original judgement that the Indians were indeed whingeing, while Bishen Bedi never quite retracted his accusation of 1976: that the West Indies indulged in deliberate intimidation, violating both the law and spirit of the game. Sunil Gavaskar has never spoken about that Test match in his long and illustrious career as a commentator and journalist; so, post-“Sunny Days” there is no way of finding out whether he stands by his original judgement. (I would think his chapter on Clive Lloyd in “Idols” is not sufficient exoneration of the latter’s strategy at Kingston, viewed in light of the fact that the book is basically a laudatory account of outstanding cricketers of his era, though a few of their foibles are randomly thrown in for good measure. And, decades after the controversial Test series, Michael Holding and Mohinder Amarnath have articulated conflicting views. The article, in addition to presenting these views and versions, has also placed each of those in appropriate context, and this it does by dint of the painstaking research that seems to have gone into its construction.

“An independent research will necessarily be a critical one, but the criticism must be balanced by sympathy or it will fail in doing justice and judging accurately” said Paul Brunton. Viewed in this light, the penultimate and final paragraphs of “Fire in Babylon – The Prelude” left no ambiguity in the mind of the reader as to where the author’s sympathies lie. Obviously and deservedly, with Bedi and his band of brave men who – irrespective of whether the fare dished out to them was legal, illegal, in the spirit of the game, or otherwise – had to cop some searing stuff from the West Indian quicks. Though the final score line of 2-1 in favour of the West Indies would scarce suggest, it is amazing to contemplate that the Indians came excruciatingly close to repeating the coup of 1971. If only rain had not washed away the first day?s play of the second test of that series, if only the Indian batsmen had cocked-a-snoop at Holding and company on the second day of the fourth test and, maybe, tided over the new ball…truly, tantalizing possibilities seem to have existed, if only in the realm of what-might-have been! With all these receiving appropriate mention in the article, there is just one thing left for me to add: Syed Kirmani’s wicket keeping in that series, as indeed in the series of 1983, was woefully inadequate, and throughout the series, many of the top-order West Indies batsmen earned numerous reprieves behind the wicket, with Venkatraghavan being the main sufferer. Surely, as one of the tour selectors, Bishen Bedi could have replaced Kirmani in the playing eleven with Krishnamurthy, who was in the tour party of sixteen, and who was the main wicket keeper in India?s victorious tour of the West Indies in 1971. (Interestingly, it was Erapalli Prasanna, Kirmani’s state teammate and captain, who ventured this suggestion in his autobiography “One More Over.” You could well argue that this mention only adds to the already overcrowded list of what might have been, but that I reckon is the charm of this bewitching game of cricket!

Comment by Madhavan Chakravarthi | 12:00am GMT 21 January 2013