Furore in Faisalabad

Martin Chandler |

In October 1961 England, under Ted Dexter, won the first Test match they ever played in Pakistan. When Mike Gatting’s side arrived for a three match series in 1987 England had not added to that single victory in the, by then, 15 Tests that they had played in Pakistan. There had, since that solitary triumph, been as many as thirteen draws together with a lone success for the home side which had enabled them to win the the 1983/84 series. They had then gone on to record a famous victory in England, again by 1-0, in the northern hemisphere summer of 1987.

Pakistan had been fortunate that when, in the early 1950s, they were first elevated to Test status, they had in Fazal Mahmood a genuinely world class bowler. By the dawn of the 1960s Fazal had lost his spark and it was not until Imran came to the fore in the late 1970s that they had such a bowler again. In the interim Pakistan cricket, particularly at home, became ultra defensive with the emphasis on avoiding defeat at all costs. In Hanif Mohammad they had a great batsman, but his attritional way of playing the game was unlikely to carve out many winning positions and with pitches prepared to suit him few games ever looked like reaching a definite conclusion. To reinforce the point it is worth noting that over this period many of the Test records that relate to slow scoring were set in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s opposition tended to be cautious as well and few trusted the local umpires who were generally regarded at best as barely competent, and at worst as downright biased. In some ways this is surprising as the leading Pakistani umpires of the time had generally, like their English counterparts, and unlike those in the other Test playing countries, played the game at First Class level. Of the five who stood in the 1987/88 series, Shakeel Khan, Khizar Hayat, Mahboob Shah, Shakoor Rana and Amanullah Khan, only Amanullah, who stood in the first Test, did not play domestic First Class cricket in Pakistan.

For England it was to be a long winter. It began with a World Cup on the sub continent in which they finished as runners up to Australia after a somewhat lacklustre performance in the final. Skipper Gatting seemed to be having some difficulties with concentration. He was certainly in form, his eight innings in the tournament all being of at least 25, but he never went on past 60, and in the final he was heavily criticised for getting out on 41 while attempting a reverse sweep to the first delivery Alan Border bowled. It was then on to Pakistan for three Tests with the prospect later of the Bicentenary Test in Australia, and then on to New Zealand for a three match series there.

The root cause of the Furore in Faisalabad can be traced back to at least 1982 and the Headingley Test between England and Pakistan, which was the deciding match of a three Test series. The game was interestingly poised late on the third afternoon with the tourists 218 runs on with Imran going well on 46 and his ninth wicket partner, Sikander Bakht, having defended stoutly and without alarm for more than an hour. At this point England tried spinner Vic Marks. There was a big appeal from the England fielders for a bat pad catch at short leg and, in what replays confirmed was a poor decision, David Constant gave Sikander out. Imran was out immediately afterwards and England eventually won by three wickets. The Pakistanis were understandably furious, particularly as they also felt that David Gower, on the way to a first innings 74, had been clearly caught behind but given not out. The replays that time were not so conclusive, but still suggested Gower had been fortunate.

When Pakistan had visited England in 1987 they asked for Constant to be omitted from the Test panel. It was not an unreasonable request and one which could have been quietly granted without anyone losing face but instead the old Test and County Cricket Board (TCCB)chose to publicly rebuff the Pakistanis. The loss of face from that rejection alone would have caused offence, and understandably so, and that must have been felt all the more acutely in view of the fact that back in 1982, when the Indian tourists had made a similar request regarding Constant, that had been acceded to.

Shakeel Khan was a poor umpire. He stood in just six Tests over a period of almost twenty years. The first match of the 1987/88 series was his third, and first for almost four years. In his first there had been seven LBW decisions against India and none against Pakistan and he had demonstrated a total lack of professionalism by talking to journalists about on field events. He had stood in one of the ODIs that preceded these Tests and demonstrated he had not improved by giving Gatting out LBW trying to sweep a delivery that pitched well outside leg stump, not that he would have seen that as he had clearly been unsighted by bowler Abdul Qadir following through in front of him. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that his appointment for the first Test was a reaction by the then Board of Control for Cricket in Pakistan (BCCP) to the David Constant episode.

The first Test was played in Lahore. The pitch was clearly underprepared and Gatting had no hesitation in batting first on winning the toss. Pakistan as a nation seemed to have temporarily abandoned the game as it began with less than 200 spectators in the ground. The reason’s given for the lack of interest were a collective disappointment at failing to win the World Cup and the retirement of the national hero Imran Khan.

Shakeel’s first error was to again give Qadir an LBW against Gatting. Again Gatting was sweeping, this time a leg break pitching on off stump. In what was doubtless taken by the hosts as a display of dissent he remained in position for several seconds before trudging off. Eight runs later Bill Athey was given out LBW by Shakeel when a long way forward and two later LBW decisions he gave, whilst being closer, still looked wrong after replays were viewed. England were all out for 175, with Qadir bowling superbly for 9-56, and while there was much controversy to come the outcome of the Test was never in any doubt after that first innings.

When England began their second innings they were 217 in arrears and facing inevitable defeat. Had Qadir bowled again at Shakeel’s end throughout the innings who knows what he might have achieved, but this time it was orthodox left arm spinner Iqbal Qasim who had the benefit of some umpiring largesse. First of all Chris Broad was given out caught at the wicket to a delivery he got nowhere near. This was the famous occasion when Broad simply refused to walk until ushered from the field by partner Graham Gooch. Ironically precisely the same fate befell Gooch a few overs later, albeit on that occasion it took a look at the replay to be certain that he had not hit the ball. Later Qadir switched ends and earned two more questionable LBWs from Shakeel, including Gatting again, as well as the wicket of David Capel, caught off his upper arm. England lost by an innings and 87.

England’s management team of Peter Lush and Mickey Stewart were both critical of the umpiring as was Gatting who said “It’s nice to compete with a team on an even basis. We weren’t allowed to perform in this match – full stop. We were cut short very early on”. Broad was not censured, a simple apology to Shakeel via Gatting being deemed sufficient. England clearly had grounds for complaint, that much is clear, but whether with neutral umpires, and in fairness to Pakistan Imran had been stridently calling for those for years without the ICC heeding his warnings, England would have been able to resist the mercurial Qadir must be regarded as highly improbable.

It was not therefore a happy England side who turned up in Faisalabad a week later for the second Test, which was to be umpired by two of Pakistan’s most experienced umpires, Shakoor Rana and Khizar Hayat. Shakoor in particular was no stranger to controversy, and he had met Gatting before, giving him out LBW twice on his Test debut. In view of what was to happen in the match it is tempting to speculate as to how thorough a historian of the game Shakoor was, and more particularly whether he was aware that the man who “caught” Sikander at Headingley back in 1982 was Gatting. Irrespective of that however he had, as indeed had Hayat, upset touring teams before. That said many took the view that the umpires might well be an irrelevance. This was because they expected Pakistan, needing only two draws to win their third successive series against England, would prepare a bowler’s graveyard. Those of that persuasion failed to take into account the fighting spirit of Pakistan’s combative new skipper, Javed Miandad, who was desperately keen to improve on the 1-0 victories of his predecessors, and with Qadir at his disposal he had every reason to believe he had the weaponry to win another Test. The Faisalabad wicket was not therefore one of those designed for breaking bowler’s hearts, and it was believed by both sides that it would break up as the game unfolded. This time England did the sensible thing and, like the Pakistanis, selected three spinners, and after winning the toss again Gatting once more chose to bat, although he had learned another lesson in Lahore, and this time told his batsmen to try and get runs on the board while they could.

The visitors started well with Gooch and Broad moving to 73 at four an over before Gooch departed, adjudged by Shakoor to have been caught at short leg by Aamer Malik from the bowling of Qasim. Gooch’s bat was tucked neatly behind his pad and got nowhere near the ball, but by all accounts it was a strident and spectacular appeal from the Pakistanis that earned the decision. At 124 Athey was also the victim of a wonderful appeal as a Qadir leg break that pitched outside leg stump jagged across him and went from his front pad into the hands of silly point – this time the decision maker was Hayat.

Gatting was understandably furious and, perhaps because of that, went on to play one of his best innings as he and Broad added 117 before Gatting went for 79, bowled by a Qadir flipper he failed to pick. England then collapsed and the last eight wickets went for 51. Only wicketkeeper Bruce French, last out for two to what looked like a poor stumping decision, had cause for complaint, but England were much more concerned about the dismissals of Gooch and Athey, which they believed cost them a match-winning total, rather than the 292 they ended up with.

Pakistan’s reply stuttered and stumbled and the first major incident took place at 75-3. England were convinced that Ijaz Ahmed was caught by Athey at silly point from the bowling of off spinner Eddie Hemmings. Shakoor wasn’t interested until he decided to warn Athey about his behaviour, the Yorkshireman having had a few choice words for Ijaz. Gatting was at slip and as Shakoor walked back to his position the stump microphone picked up the following exchange:-

Gatting: It’s alright, off you go. we said nothing , thank you.

Athey: The sooner we get home the ****ing better.

Gatting: One rule for one, and one for another.

In point of fact it mattered little as a few minutes later Pakistan were in all sorts of trouble at 77-5 with just Salim and Aamer Malik (unrelated) between England and their tail. There was around an hour of the second day left during which these two added 29, the watchful Aamer’s share being just a single. There was just one controversial incident, when Salim had cause to complain to Shakoor that square leg had moved deeper behind his back and without his being informed, and Shakoor duly warned Gatting.

It is worth digressing at this point to look at that particular issue which is one that is not covered by the laws of the game and is a matter of etiquette. Conventional practice had generally been that no fielder would be moved without the batsman being told and this seems to have held sway in England up until the 1970s after which the situation changed, and it became part of the non-striker’s job to bring any relevant alteration in the field to his partner’s attention. This was a pragmatic development rather than a sea change, brought about by the rise in England of one day cricket and the great increase in the frequency of field changes that accompanied that.

The cause of the unseemly dispute that gives this feature its title was the action of Gatting in bringing deep square leg up in the last over of the day. In fact Gatting, and bowler Hemmings, both let Salim know what was happening. It seems that Shakoor, at square leg at the time, did not hear this and that all he saw was Gatting’s gesture to the fielder, Capel, to indicate he had come in far enough. Context is important here. Gatting genuinely believed he would have done nothing wrong had he not told Salim of the change, but had done so anyway. Shakoor, on the other hand, took the view that having got away once with going against the spirit of the game that Gatting was trying to do so again. Small wonder therefore that both of these proud men felt very strongly about what they perceived as having happened.

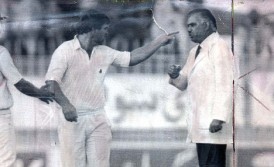

Shakoor called out and hurried in and there was an exchange between him and Gatting before Shakoor walked off back towards square leg. Gatting, it seems, called Shakoor a “**** umpire” before, on his way back, Shakoor turned back and called Gatting a “****ing cheating ****”. At this point it is also worth remembering that English was not Shakoor’s first language – he may well have not appreciated the significance of the difference between accusing a man of being unfair, as opposed to being a cheat. There followed the infamous finger-jabbing exchange which, briefly, saw cricket on the front pages of newspapers the world over.

At the close of play the England camp did not realise how important the incident was to become and nothing was really said at their press conference that evening. In another part of town however Shakoor was also talking to the press and making it clear that he did regard it as a big issue, and that without an apology he would not take the field again. In fact England did not learn of this until they got to the ground on the third morning.

The England team were out on the pitch for the scheduled start of play but they were there alone and the few hundred spectators in the ground were never going to be enough to force the issue. So it was then that the whole of the third day, and the following rest day, were taken up with discussions about resolving the impasse. Eventually, having been more or less ordered to do so, Gatting handed a terse note to Shakoor on the morning of the fourth day that apologised for the bad language used. What had earlier been agreed in principle was that there would be two apologies, and that accordingly Gatting would receive one from Shakoor for his use of foul language towards Gatting. Drafts were in the process of going back and forth when it seems that the Foreign Office intervened and told the TCCB to sort the matter out whatever the cost. It was enough for the fourth day to start just a few minutes late, but only briefly as bad light ate heavily in to the day and although England gained a first innings lead of 101 too much time had been lost and the game meandered to a draw.

Did Shakoor dig his heels in of his own volition or was he prevailed upon to do so? At the time many believed that Javed had actively encouraged Shakoor to maintain his position in order to save Pakistan from the looming possibility of defeat. He said little at the time but in his 2002 autobiography, Cutting Edge, Javed said “It is often claimed that I was the one who urged Shakoor Rana to demand an apology from Mike Gatting. This is absolutely true.” Javed does not say that he did this to try and avoid defeat, and claims that he took a strong line as he felt his country had been insulted. I am not convinced about that but he does make the valid point that had it been he and not Gatting who had behaved in such a manner towards an umpire that English public opinion would have demanded much more than an apology.

Contemporary English writers seem not to have been fully aware of another point made by Javed that being that the BCCP were prepared at one stage to tell Shakoor to continue or be replaced, but that when they tried to find another umpire who would be prepared to officiate all refused. It was known that the stand-by umpire, and the Pakistan Umpires Association were backing their man, but I have not read anywhere other than in Javed’s book that this would have been a solution the BCCP would have settled for. I suppose to accept the appointment at that stage would have placed whoever undertook the job in an impossible position, but it does seem surprising that it was even contemplated – presumably in truth the BCCP were as concerned at the legal and financial implications of losing the rest of the tour as the TCCB were.

Not surprisingly Gatting’s team had been four square behind him and there had been talk of the team refusing to play on themselves. They felt that the much vaunted “best interests of the game” would be served not by some cobbled together compromise but by the wheels coming off the tour and the deplorable umpiring exposed. The unprecedented step was taken, in clear breach of the players’ contracts, of issuing a joint statement in support of their Captain. All the major incidents were on camera and they might have been on strong ground had it not been for the fact that, whatever provocation there might have been, the shows of dissent by the England players generally, and Gatting in particular on that momentous evening, simply have no place in professional sport and cannot be tolerated.

Naturally the choice of umpires for the final Test was a tricky one. The BCCP initially proposed Hayat and Shakeel, which duly brought howls of protest from the England camp. BCCP gave England the choice, but no neutrals were willing and available so they ended up with Mahboob Shah, who had umpired the World Cup final without complaint, joining Hayat. The Test was duly drawn, with there never being any prospect of a definite result, and the Pakistanis completed their third successive series victory against England. What about the standard of umpiring in the match? Scyld Berry, who wrote the only contemporary book on the tour, A Cricket Odyssey, and who was more than happy to lambast the umpiring decisions made earlier in the series, described it as “exemplary”. For once in a country where, to that date, touring batsmen had been given out LBW almost twice as often as home batsmen (197 as against 101), there was not the slightest suggestion of either bias or incompetence.

After the final Test Tour Manager Lush was able to tell Gatting that the TCCB had authorised the payment of a GBP1,000 bonus for each member of the touring party. Given the disciplinary lapses and the clear breach of contract by the players it seems unlikely that Gooch was alone in the thought that, when he initially heard about this sum, that what was being announced was a fine rather than a bonus.

The party were naturally relieved to leave Pakistan but the rest of the tour was not a happy one. All four Tests in Australia and New Zealand were drawn and disciplinary problems continued to affect England. In the Bicentenniel Test Broad smashed down his stumps in anger after being bowled for 139, and in New Zealand Graham Dilley was fined for shouting an obscenity when an appeal for LBW was turned down.

Many, including Gatting himself were, after a period of reflection, surprised he was not sacked as captain after the Pakistan tour, but he did not have long to wait. The still all-conquering West Indies were England’s guests in 1988, although under Gatting England emerged with considerable credit from the first Test which they drew comfortably. A tabloid newspaper however managed to run a story accusing Gatting of sleeping with a young female member of staff at the team’s hotel. Gatting denied anything untoward took place, an account that the TCCB accepted, yet perversely they still decided to sack him for “improper behaviour”.

Normal service was resumed for the rest of the series and England lost each of the four remaining Tests. Gatting, understandably, lost all faith in the TCCB and doubtless his subsequent decision to lead a “rebel” side to South Africa in January 1990 was heavily influenced by this ridiculous decision. He did, perhaps, have the last laugh as he returned to the official England side later. The decision to dismiss Gatting was not in itself a bizarre decision, but the reasoning was. Gatting was a decent skipper, as his record at county level amply demonstrated, but for England he won only two Tests out of the 23 for which he was in charge, although those two victories did mean that the 1986/87 party to Australia won a series there for what was to prove the last time until earlier this year. But ultimately no contrived excuse was needed – no one, least of all Gatting himself, could have complained if he had lost the England captaincy purely by virtue of his lack of success, or indeed if he had been dismissed simply for his role in the Furore in Faisalabad.

What would have happened today? The match would have been played under the watchful eye of an ICC Match Referee charged with the duty of enforcing the ICC Code of Conduct. The details of the incident itself do not sit entirely comfortably with any of the situations specifically referred to the Code, so before deciding on a punishment the referee would have had the tricky job of deciding what level of breach he was dealing with. Level 1 carries only a financial sanction, but Level 2 brings the possibility of a one match ban. Levels 3 and 4 carry an automatic ban, and the only issue is its duration. A sympathetic referee might just have decided that Gatting’s actions were at Level 2, although my own view is that most, taking into account all of the circumstances and particularly that the Code expressly forbids consideration of the fact that the umpire may be wrong, would have found his conduct to have reached Level 3 and that as a consequence an automatic ban of between two and four matches would have applied, with the loss of the captaincy inevitably following. Were the leadership to have been lost because of a ban it is difficult to imagine the TCCB would have restored it on the expiry of the disqualification under any circumstances, and certainly not when the team had been as unsuccessful as they had been during Gatting’s tenure.

A very good read – thanks for putting it together. LOL at Javed’s suggestion that he went out of his way to hold up the match for any reason other than to protect his side’s 1-0 lead in the series. :laugh:

Not that the TCCB came out of the affair with any credit whatsoever.

Comment by wpdavid | 12:00am BST 20 June 2011

Great Article and very informative . Writing on such controversial issues is not easy, kudos for being fair to both sides of the story.

Comment by Sanz | 12:00am BST 20 June 2011

I do think there was biased home umpiring but I also feel that the visiting teams along with their press did over play the biased aspect to hide their own shortcomings. My father still goes how we were robbed of a series win in WI in 88 with the same happening in NZl in 85 and also in England during the 82 tour.Neutral umpires have atleast eliminated this type of whinging from the modern game.

Comment by Xuhaib | 12:00am BST 21 June 2011